Approaching the summer vacation, the end of July was deemed extremely eventful for NCA enforcement actions. On 18 July, the Italian Competition Authority (ICA or AGCM) triggered a sanctioning proceeding against Google with respect to the submission to users of a request for consent to the linking of the services they offer. A few days later, the Spanish Competition Authority (SCA or CNMC) announced it is investigating Apple for conduct relating to its imposition of unfair commercial terms on developers who use the App Store to distribute applications to users of Apple products.

Both these conducts tremendously resonate with the terms in which gatekeepers submitted their compliance solutions abiding by the DMA. Perhaps, more than they should. The DMA is about promoting contestability levels and ensuring fairness in the digital sector. Simultaneously, it is also premised on the harmonisation legal basis contained under Article 114 TFEU. The regulation centralises its enforcement system to the European Commission and confers powers pertaining to a secondary role to the NCAs. In parallel, however, Article 1(6) declares the DMA applies without prejudice to the application of Articles 102 TFEU and national competition rules prohibiting other forms of unilateral conduct. The two sanctioning proceedings follow the trail of bread crumbles secured by Article 1(6). Notwithstanding, they dangerously approach the fine line of the DMA’s scope of application.

The two sanctioning proceedings: unfair is the new black

Unfairness is quite an elusive concept. It means different things to different enforcers and fields of law. Unfair in the DMA, as set out under Recital 34, means that imbalances in rights and obligations prevail in relationships between business users and gatekeepers. According to the European Commission on its recent interpretation of unfair trading conditions under Article 102(a) TFEU, the pursuit of fairness under the DMA and Article 102 TFEU diverges in terms of objectives (para 551 of the decision under Case AT.40437). For instance, anti-steering is prohibited under Article 5(4) due to its unfair character and that finding “supports the EC’s view that such conditions imposed by a dominant undertaking should be qualified as unfair” (para 552). Thus, unfairness in the DMA purports unfairness under Article 102 TFEU, although the EC establishes that unfair conditions are those that “are not necessary or proportionate for the attainment of a legitimate objective (…) without having to show that they have an unacceptable impact” (para 553).

Building further on this dichotomy, in the area of consumer protection, unfair commercial practices manifest in two different ways: i) if they are contrary to the requirements of professional diligence and materially distort or are likely to materially distort the economic behaviour with regard to the product of the average consumer whom it reaches or to whom it is addressed; or ii) if they fall within the category of misleading or aggressive in the sense of Articles 6 to 9 of the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive (Articles 5(2) and 5(4) of the UCPD). In the context of the GDPR, however, the principle of fairness is benchmarked against the yardstick of reasonable expectations and the limitation of not imposing unjustified adverse effects on the data subjects.

The AGCM and CNMC’s opening of sanctioning proceedings hint at the idea that they will be exploring some of the aspects of fairness. On one hand, the Italian competition authority takes issue with the consumer protection perspective. Given that the Italian NCA also bears a consumer protection mandate from its institutional design, it will check via its sanctioning proceedings whether Google’s prompt asking for consent for the ‘linking’ of the processing of its personal data is misleading and/or aggressive. In particular, the press release points out that the prompt is “accompanied by inadequate, incomplete and misleading information and it could influence the choice of whether and to what extent consent should be given”. Preliminarily, the ICA highlights the prompt basically provides no relevant information as to the effect that consent has on Google’s use of the personal data of users. On the other hand, the Spanish competition authority goes back to unfairness in the sense of Article 102(a) TFEU and will investigate whether Apple imposed disproportionate and unjustified terms and conditions upon its developers operating at the App Store.

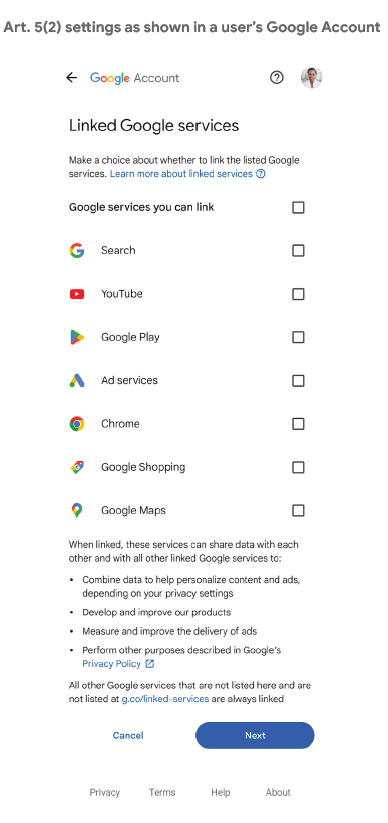

In reality, both sanctioning proceedings relate, in some way or another, to how Apple and Google proposed to comply with the DMA. The ICA’s sanctioning proceeding is particularly focused on the request for consent that Google submits to its users to the linking of its services. Thus, the press release implicitly reads as scrutinising Google’s compliance solution introduced as a consequence of the regulatory requirement set out under Article 5(2) DMA. The prompt the ICA is referring to is the same one that Google included a screenshot of in its compliance report, as shown in the picture below:

In parallel, the Spanish competition authority’s sanctioning proceedings seeking to determine whether Apple abused its dominant position relating to its distribution of apps focuses on the terms that most developers enjoy when distributing their apps on iOS: the regular Terms of Service Apple imposes to its developers. It is not, therefore, contesting whether the New Business Terms -that the European Commission is already analysing under its third non-compliance procedure as provided by the DMA- infringe Article 102 TFEU.

As I already pointed out, the DMA allows (and does not hinder) the possibility of the NCAs to capture the conduct of the gatekeepers via these means, bearing in mind that they do not seek to apply the DMA’s terms and legal standards in any fundamental way. As a matter of fact, the principle of double jeopardy, as interpreted by the Court of Justice in its latest bpost (Case C-117/20) and Nordzucker (Case C-151/20) rules, provides more leeway to the NCAs to apply Article 102 TFEU in this context. The DMA is sharply clear in its complementarity with regards to EU competition law.

As such, therefore, public authorities may seek complementary legal responses to the same conduct through different procedures forming a coherent whole to address the different problems (para 49, bpost). The only limitations that the Court of Justice places for those parallel sets of enforcement are that i) there are clear and precise rules making it possible to predict which acts or omissions are liable to subject to duplication of proceedings and to predict there will be coordination between the two competent authorities; ii) the two sets of proceedings have been conducted in a sufficiently coordinated manner within a proximate timeframe; and iii) that the overall penalties imposed correspond to the seriousness of the offences committed. In principle, Articles 37 and 38 DMA enshrine the mechanisms that the NCAs must follow so to keep both paths of enforcement sufficiently coordinated. That does not necessarily mean that the NCA’s enforcement actions are entirely different in terms of the legal reasoning underlying them. Despite the stark differences in the manifestations of fairness, it may well be the case that the same legal reasoning underlies each of them to produce different legal consequences for the undertakings.

Even if it might sound counter-intuitive, nothing would stop NCAs from doing so. Notwithstanding, there is a huge scope for legal conflation across legal fields and concepts once the DMA has been adopted. There is the temptation on the side of the NCAs (and also on the EC’s side) to transplant the trick that might have worked in scrutinising gatekeeper conduct at one level into another radically different area premised on different legal objectives.

The AGCM’s sanctioning proceeding overlaps with Article 5(2) DMA

Article 5(2) DMA is one of the most prominent provisions embedded in the DMA. It prohibits the processing, combination and cross-use of personal data across core platform services (CPSs) and, in some cases, with personal data from the gatekeeper’s proprietary services and from third-party services. Although the European Commission has not (yet) taken issue with Alphabet’s compliance solution relating to Article 5(2) DMA, the mandate has merited the EC’s attention as far as Meta’s consent or pay subscription model is concerned.

A few days after the initial compliance deadline set out for March 2024, the EC triggered a non-compliance procedure under the DMA against Meta on the grounds of its implementation of Article 5(2) DMA. The EC’s preliminary findings already established that Meta’s subscription model did not meet the necessary requirements set out under Article 5(2) because it does not, inter alia, “allow users to exercise their right to freely consent to the combination of their personal data”. At face value, therefore, the EC interprets that introducing a new monetisation model based on data processing does not meet the legal standard of the DMA. In parallel to the EC’s preliminary findings, the EDPB also issued its Opinion 08/2024 on Valid Consent in the Context of Consent or Pay Models Implemented by Large Online Platforms declaring that subscription models similar to those proposed by Meta do not abide by the terms of the GDPR.

Google’s compliance solution stands in stark contrast to Meta’s: it does not introduce a fundamental shift to the monetisation of its business model, but it does propose a radical transformation to Alphabet’s data flows. The ICA is not entirely worried about the underlying data infrastructure introduced by Alphabet, but rather about how the undertaking frames those choices to end users. Ironically, it could be argued that the DMA already covers that front via its anti-circumvention clause. Article 13(6) DMA declares that the gatekeepers shall not subvert end users’ autonomy, decision-making, or free choice via the structure, design, function or manner of operation of a user interface or a part thereof. This sounds terribly similar to the AGCM’s line of reasoning as set out in its press release, where it seeks to determine the aggressiveness of the prompt by taking similar terms to those already contained under the regulatory instrument.

The Spanish competition authority’s overlap with Article 6(4) DMA

Article 6(4) mandates operating systems to facilitate alternative distribution channels for apps and app stores. Apple’s iOS ecosystem is the most concerned with the provision’s application. To this call, Apple fundamentally proposed a set of New Business Terms that its developers could opt into if they wanted to seize the opportunities generated by the DMA’s provisions. For instance, if developers wish to distribute their apps on other channels different to the App Store, they must first accept the New Business Terms, which entail, for example, the imposition of a new fee structure (see a general comment and description of those compliance solutions here).

The untold truth about Apple’s compliance strategy is that in parallel to its re-working of its 30% fee imposed on all digital transactions, most of its digital business has basically stayed the same. In other words, most app developers have not opted into the New Business Terms and, therefore, do not enjoy the business opportunities that the DMA provides them with. This is precisely the conduct that the Spanish competition authority’s sanctioning proceedings aim to capture: the business terms applied to developers when distributing their services on the App Store. Implicitly, if a developer does not wish to distribute via alternative means as opposed to the App Store, it has no need to opt into the New Business Terms.

Despite the fact that these ‘original’ terms have remained untouched, that does not make them less capturable by the DMA. Even though they are not a part of Apple’s DMA compliance plan, the regulation does touch upon them because the DMA must not apply selectively to some business users and not others. The European Commission has already remarked on this same fact twice on two of the non-compliance procedures opened against Apple for its lack of compliance with Articles 5(4) and 6(4) DMA. In both cases, the EC shed light on the obscured ‘original’ terms that still apply to the majority of Apple’s business users. Under those procedures, the European Commission will assess whether this false dichotomy meets the mandate of compliance by default introduced by the DMA.

In this context, therefore, it seems confusing that the Spanish competition authority will capture precisely those same terms so as to determine whether they are unfair (disapplying the DMA’s definition, no doubt) under Article 102 TFEU and the national equivalent. Up to three different scenarios could be given as a consequence of the overlap. First, neither the EC nor the CNMC declares that Apple’s original terms infringe any of these norms. In my own mind, this seems the less likely outcome. Second, the EC declares that Apple’s ‘original’ business terms must be adapted or scratched out as a potential compliance solution for the DMA because they fail to meet the threshold of effective enforcement. This is the most likely outcome since it is quite clear that the ‘original’ business terms do not comply with Article 6(4) DMA. The design of Apple’s false dichotomy is precisely set out under these terms to delay compliance as much as possible. The CNMC, however, may equally find that those business terms simultaneously infringe Article 102 TFEU, because they additionally are disproportionate and unjustified in terms of, for example, the fee charged to developers (how justified must a fee be so as to escape the capturing via antitrust?). Or, on the contrary, and third, the Spanish competition authority may not find any evidence that adds something new to the EC’s sanction under the DMA. Wouldn’t that be a resource-intensive expense that could have been easily absorbed by the EC as the sole enforcer of the regulation?

Three is one too many?

The NCA’s contributions in the discussion around the gatekeeper’s compliance solutions advocate further the case for duplication of proceedings across different fields of law regarding the precise same conduct. It may well be the case that they uncover parts of the same conduct which are illegal for different reasons than those directly contained under the DMA. In parallel, however, this motion might put a hold on the EC’s enforcement powers, especially when interpreting the anti-circumvention clause in coherence and accordance with other fields of law.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Competition Law Blog, please subscribe here.