As the deadline for compliance with the provisions of the Digital Markets Act is fast approaching, the designated gatekeepers are progressively proposing and implementing changes to their business models (for an extensive analysis of the designated CPSs see here and here). Apple’s recent announcement proposes to implement changes on its operating system (iOS), web browser (Safari) and software application store (App Store) in the European Union. It is the most wide-encompassing and far-reaching proposal as opposed to all of the solutions that have been put forward by the designated gatekeepers.

The highlights of the announcement include: i) Apple’s opening up its formerly closed walled garden-like ecosystems for competing app marketplaces and app developers; ii) the ecosystem holder’s new technical implementations break down on the former tight grip on the hardware and software functionalities of its devices, notably on payment processing and via a dedicated interoperability process; and iii) the introduction of new business terms for app developers regarding app distribution and alternative payment processing. The changes entail Apple’s immediate response to the high standards set out by the wide array of the DMA’s provisions that the gatekeeper will have to apply starting in March 2024. The new capabilities will be rolled out in iOS 17.4 and become available to users in the 27 Member States beginning in March 2024.

The blog post navigates the transformations proposed by Apple in light of the obligations set out in Articles 5, 6 and 7 of the DMA and the wider objectives of contestability and fairness that the regulatory framework strives to pursue.

Side-loading and the case for inter-platform competition

In its announcement, Apple communicated that substantive changes would apply to the architecture surrounding its main operating system: iOS.

First, it will allow alternative marketplace developers to create alternative app marketplaces, under the condition that they assume the significant responsibility and oversight of user experience in managing those same marketplaces. In practice, this means that inter-platform competition will increase as a result, given that Apple’s proprietary App Store will face rivalry at the marketplace level. Default settings on app stores will be eliminated as a result. Second, the ecosystem holder proposed to enable alternative distribution of iOS apps via those alternative app marketplaces. Subsequent to the green light conferred upon the creation of alternative app marketplaces, third-party app developers may distribute their apps on other channels that do not necessarily correspond with those of Apple. Third, Apple will grant developers a dedicated process to request interoperability with iPhone and iOS hardware and software features. Finally, Apple abandons its former policy to only allow web browsers to run on its proprietary browser engine WebKit and will provide that alternative browser engines may support browser apps within its ecosystems.

The evident impact of the changes on contestability and fairness may seem overall positive from the perspective of the DMA, but a closer look at the nitty-gritty of the procedures that Apple has introduced alongside its press release paints a completely different picture.

Alternative app marketplaces are supported on iOS, but friction prevails

In appearance, Apple’s proposal to enable third-party app marketplaces to enter its ecosystem corresponds to enhancing inter-platform competition (the concept was first used in the context of the DMA by Petit here and here). That is, the proposed technical implementation, in principle, lowers the barriers to entry at the platform level in line with Article 6(4) DMA.

The provision requires “gatekeepers (to) allow and technically enable the installation and effective use of third-party software applications or software stores using, or interoperating with, its operating system and allow (them) to be accessed by means other than the relevant CPSs of the gatekeeper”. The provision requires that gatekeepers may legitimately take measures to ensure that the entry of those alternative marketplaces does not endanger the integrity of the hardware or operating system. However, gatekeepers may not impose those restrictions without any limitation, their capacity to curtail this capacity is determined by two distinct requirements: i) that those measures are strictly necessary and proportionate to minimising security risks on their services created by the entry of the third-party marketplace developers; and ii) that those measures are duly justified by the gatekeeper.

Despite Apple’s good intentions in its press release, if one analyses Apple’s Developer Support page, the requirements that alternative marketplace developers will have to face to create their alternative app stores are nothing short of extensive. In principle, Apple defends that they are introduced to reduce the new risks posed by the creation of new avenues for malware, fraud and scams, illicit and harmful content and other privacy and security threats, which it has less ability to address due to the DMA’s provisions.

Perhaps the narrative of introducing alternative players into the ecosystem could have tricked some into believing that Apple is breathing openness into its ecosystem architecture. However, Apple’s dedicated rules still maintain the ecosystem holder’s grip over the apps and the functioning of its devices. The most salient evidence of this is demonstrated via the fact that Apple will maintain its power to authorise marketplace developers to distribute dedicated marketplace for iOS apps after meeting specific criteria and committing to meeting ongoing criteria in protecting users and developers (in technical terms, Apple’s Alternative App Marketplace Entitlement). Alternative marketplace developers will hold responsibility for operating their app stores, which seems reasonable. Additionally, Apple will also require that these marketplace developers agree to the new business terms that it has presented to its developers as an opt-in system. In particular, marketplace developers will be charged by Apple 0,50€ for each first annual install of their marketplace app, if they are not exempted from paying it because they are granted the fee waiver based on their condition as an accredited educational institution, nonprofit organisation or government entity.

This fee, which Apple has coined as the Core Technology Fee (CTF), is the point where the ecosystem holder has faced the most backlash from the industry. In Apple’s own words, the value that Apple provides to marketplace developers with their ongoing investments in developer tools, technologies, and program services is reflected in the CTF. It will also be charged to all the developers who decide to change to the new business terms proposed by Apple (more on that in the next section). For the case of marketplace developers, no exemption applies to them, so every single annual install of their app marketplace will correspond to 0,50€ owed to Apple.

Apple’s definition of a first annual install is wide. It encompasses an app’s first-time install, a reinstall, or an update from any iOS app distribution option in a 12-month period. In practice, this means that an install of an alternative marketplace will not be accounted for just once, but as many times as different updates that the operator decides to make, regardless of the consumer’s use of the app store. For example, if an iPhone user decides to install a competing AltStore marketplace in March 2024 (which is already officially planning to launch its app store in the EU), 0,50€ will be charged. If the user does not eliminate the app and the app is subsequently updated say, in May 2025, a second first annual install will be quantified, despite that the material user base of the marketplace has not substantially increased.

The wide definition of first annual installs undermines the developer’s incentives to publish updates on their features and penalises them for bearing a large existing user base (as highlighted by Seufert here). Furthermore, the fact that CTF is framed per install of the marketplace developer introduces friction for them to reach sufficient scale to be able to compete on the merits with Apple’s proprietary App Store (as pointed out by Geradin here). Aside from that, Apple will only authorise those marketplace developers via its Alternative App Marketplace Entitlement procedure when it can establish that it possesses adequate financial means to guarantee support for developers and customers by providing it with a stand-by letter of credit from an A-rated financial institution of €1,000,000, which will have to be renewed every year. CEO of Epic Games Tim Sweeney has already coined the requirement as placing “an enormous disadvantage” for startups that wish to ramp up adoption on their competing app marketplaces, whereas other players of the industry have recognised that it may be a legitimate manner in which Apple ensures that scam alternative marketplaces do not enter its ecosystem, despite that it raises a significant barrier to entry for them.

One must bear in mind, however, that these requirements are built on top of the cost and fee structure that the alternative marketplaces will impose on their developers. Despite that some potential entrants to the marketplace distribution of apps have already announced that they will publish their apps for free (for example, AltStore proposes deep Patreon integration so that developers can distribute Patreon-exclusive apps to their patrons), the business models and cost structures of alternative players will not necessarily follow this same path.

Leaving aside the requirements imposed on developers, the implementation of the change from the perspective of user experience is not much more encouraging in terms of its coherence with Article 6(4) DMA. The alternative marketplace will only be available for its installation from the marketplace developer’s website. Notwithstanding, the end user will not be able to directly install the alternative app store. Prior to that, the end user will have to navigate into the configuration of the device’s settings and activate the control ‘Allow Marketplace from Developer’ so that the download can be successfully completed.

From recent experience in the analysis of similar changes introduced by Apple on its privacy policies, one can guess that Apple’s requirement to subject users to prior approval of the option via their device’s setting options may be held as discriminatory in nature and, thus, contrary to the spirit of the DMA’s levelling of the playing field.

Side loading and a new brave world: are developers best off?

The logical consequence of the impact of Article 6(4) DMA on the introduction of distinct app stores into ecosystems held by undertakings in a gatekeeper position is to expect that they are not void from any content. The provision is two-pronged: it compels gatekeepers to allow and technically enable the installation of third-party software applications and to enable their effective use. There is no better and more effective use of these alternative marketplaces than by allowing developers of apps to upload their own products.

To that end, Apple has finally proposed that it will enable side-loading to developers to offer their apps for download from alternative app marketplaces. In theory, a fully-fledged manifestation of side-loading does not only include downloading apps on third-party and alternative marketplaces distinct to Apple’s proprietary software application store, but also apps that may well be directly downloaded from websites without the intermediation of an app store (the so-called web apps, as stakeholders already remarked in the third workshop held by the European Commission see a review of it here).

The narrow definition of side-loading is paired with the fact that the possibility of distributing apps on other alternative marketplaces is only open to those developers who agree to the relevant business terms for apps that Apple has tailored to exclusively apply in the EU. In other words, developers who do not explicitly opt-in to the new business terms that Apple has presented and that will start to apply in March 2024 (they may agree to the terms at any given point in time, according to Apple) are automatically and technically hindered from distributing apps in non-native app stores.

Four types of distribution will emerge in Apple’s ecosystem as a result (in the EU): i) the distribution of apps based on the ‘traditional’ business terms, i.e., a 30% fee on App Store transactions and regular subscriptions; ii) the distribution of apps based on the new business terms in those cases where developers do not distribute in non-native app stores; iii) the distribution of apps based on the new business terms involving dual distribution, i.e., on the App Store and alternative marketplaces; and iv) the distribution of apps based on the new business terms exclusively performed via non-native app stores.

The choice is, however, not trivial, since it already overlaps with a different provision engrained into the DMA: Article 6(12). The obligation compels Apple to apply fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory general conditions of access for developers who wish to operate on its software application stores listed in the designation decisions. That is to say, the reach of Article 6(12) meets the conditions that gatekeepers (in this case, Apple) impose on business users (i.e., developers of apps) on their own software application stores. The provision does not impose an equivalent obligation on the conditions that the gatekeeper may impose on software application stores operated by third parties (which are, no doubt, not listed under the European Commission’s designation decisions).

Due to this reason, the provision encompasses the first three scenarios that I outlined, but it may well be more questionable whether the last scenario remains captured, given that Apple would, indirectly, impose (to some extent) general access conditions for developers to distribute apps on non-native app marketplaces.

In any case, those new business terms for apps introduce a new fee structure for developers and open new options for the developer’s use of alternative payment service providers directly on their apps or via link-out.

On the side of the ecosystem’s fee structure, Apple lowers the commission fees it requires from developers. Three different tiers of fees are introduced: the reduced commission, the payment processing fee, and the Core Technology Fee.

The reduced commission alternatively applies depending on the type of transaction that is completed in the ecosystem. The 30% fee is reduced to 17% on transactions for digital goods and services, which will apply regardless of the payment options that the developer displays on its apps. Alternatively, the rest of the services, such as subscriptions following their first year, will be charged a 10% fee.

The payment processing fee will be additionally charged in those cases where the developers choose to use the App Store’s payment processing services for an additional 3% fee. This is the only commission that developers may dodge if they decide to implement alternative payment processing services into their apps. Despite the alternative payment processing, this will not be the case for payments processed on apps on iPadOS, macOS, watchOS and tvOS in the EU, which will get a 3% discount on the fee they owe to Apple. Moreover, this discount does not apply on the baseline of 17% but on the App Store’s standard worldwide commission rate, i.e., 30%.

The CFT fee, which I have already reviewed in relation to the marketplace developers, charges 0,50€ for each first annual install per year. In the case of app developers, Apple applies an exemption for the first 1 million installs that are performed on the app. Thus, apps downloaded below the threshold of 1 million installs will not be forced to pay anything. That is the reason behind the fact that Apple estimates that 99% of developers would reduce or maintain the fees they owe to Apple and less than 1% of developers would pay a CFT on their EU apps. Even if developers do not automatically meet the 1 million threshold, they are compelled by the terms to report back to Apple on their transactions. Based on that reporting, Apple charges the CFT if the threshold is surpassed on a monthly basis.

According to Apple, the new fee structure allows Apple to create value for the business of developers via distribution and discovery on the App Store, the App Store’s secure payment processing, Apple’s trusted and secure mobile platform and all the tools and technology that it builds and shares to foster innovative apps with users around the world. The industry’s reaction has been nothing but short of harsh. Sweeney termed the CFT as a “junk fee” and the new fee structure as arbitrary and exploitative. Some estimates directly relating to the CFT have calculated, using Apple’s fee calculator functionality, that $10 million in sales under the new fee structure would entail that Apple would take a $6.2 million annual cut.

On the side of Apple’s introduction of alternative payment service providers, the new rules are paired up with the developer’s agreement with the new business terms, too. By this token, the application of the new fee structure is contingent on developers benefitting from the possibility of accessing alternative payment service providers within their apps. The new options introduced by Apple in terms of payment take two different forms: i) the direct offering of alternative payment processing for digital goods and services embedded in their own apps; ii) the completion of those payments through link-out, that is, through the developer’s external website. Again, just as in the case of alternative marketplace developers, if developers wish to enable these options within their apps they will have to follow authorisation via Apple’s proprietary and dedicated entitlement procedures (StoreKit External Purchase Entitlement for direct payment processing and StoreKit External Purchase Link Entitlement, see the technical details here). For the particular case of payment processing completed via link-out, Apple briefly touches upon the anti-steering prohibition under Article 5(4) DMA and enables developers that have been authorised to inform users of their promotions, discounts and other deals available outside of their apps. For the moment being, the option is only available in this narrow context.

Developers are not encouraged to expand their choices for consumers in terms of payment processing. On the contrary, Apple hinders developers from cumulatively offering its own proprietary payment processing option (in-app purchase or IAP) and an alternative payment processing venue. The justification for forcing the developer’s hand into selecting one of these two options, Apple argues, is justified “due to the App Store’s tight integration with in-app purchase and to reduce confusion for users”. Therefore, the binary choice opens a myriad of different scenarios before the developers, stemming from the four situations outlined above. Given that the choice for catering alternative payment processing is contingent on the developer’s opting-in to the new business terms offered to them by the ecosystem holder (the Alternative Terms Addendum for Apps Distributed in the EU), the payments that are processed via alternative payment service providers will equally be charged with the ‘reduced’ commission when those payments relate to transactions for digital goods and services.

In a similar vein to the business terms relating to the new fee structure, the options surrounding the technical implementation of alternative payment processing are covered by the conditions of fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory general conditions access for business users to software application stores under Article 6(12) DMA (in fact, Recital 62 DMA includes this type of conditions as examples to the provisions). Notwithstanding, a similar word of caution must be advised against its all-encompassing application. Those scenarios where developers trigger the entitlement process to cater for alternative payment processing services for their use on apps available on the App Store are covered by the provision. The requirements imposed by Apple are, thus, subject to the scrutiny of regulation. It is more doubtful that the application of those same conditions on third-party app stores will be equally covered by the same high threshold requirements.

These conditions are, however, subject to the general prohibition under Article 5(7) DMA that compels gatekeepers to “not require end users, to use, or business users to use, to offer or to interoperate with (…) a payment service, or technical services that support the provision of payment services, such as payment systems for in-app purchases, of that gatekeeper in the context of services provided by the business users using that gatekeeper’s CPS”. As opposed to the narrow scope of Article 6(12) DMA, the reach of Article 5(7) is wider. Taking the example of Apple’s renewed business terms relating to alternative payment processing services, the prohibition applies to all the payments that are processed across the ecosystem, since the payment services are not only related to those processed on the apps distributed through Apple’s App Store (designated as a CPS by the European Commission) but on all the apps distributed on the wider operating system iOS. Apple even takes it a step further and those business terms will equally apply to the App Store catered through iOS, iPadOS, macOS, watchOS and tvOS, although a different fee structure will apply.

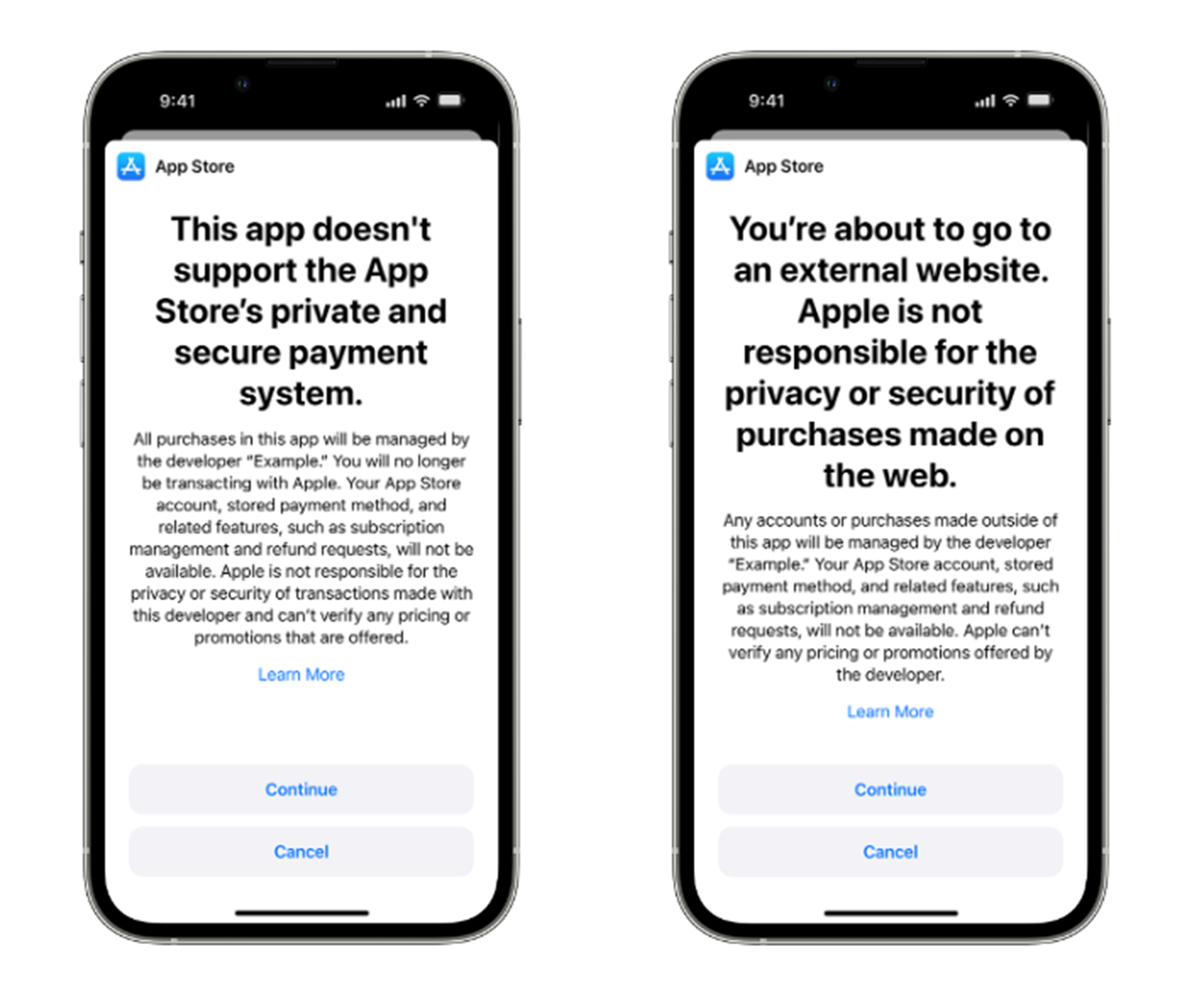

From the end user perspective, compliance with Article 5(7) DMA cannot be understood to be completely frictionless. The concerns that competition authorities, such as the Dutch competition authority, already raised regarding Apple’s business terms for dating apps in the Netherlands will be repeated by the European Commission. Each payment flow and each flow to enter payment information (even if it is not for a specific purchase) that an end user engages in through alternative payment service providers will have to be preceded by a disclosure. In Apple’s own words, the disclosure is aimed at “help(ing users) understand that the purchase isn’t backed by Apple”. In a similar vein to Apple’s previous encounters with competition authorities in proposing remedies to put an end to their infringements with Article 102 TFEU, Apple imposes the design, wording, and formatting of the disclosure, which will follow along the lines of the pictures displayed below:

As a consequence of the imposition of these templates, competitors have already denounced that Apple’s new dedicated terms constitute yet another attempt to circumvent the regulation, alike similar iterations that Apple held against opening up its ecosystem in the United States, the Netherlands (in the dating apps-case) and South Korea. Those assertions may well be true (and sanctioned in the near future by the European Commission) in light of the DMA’s anti-circumvention clause established in Article 13(6).

Aside from the prohibition under Article 5(4) and the conditions of access imposed on Article 6(12), a violation of the regulatory instrument will not only be declared when the gatekeeper omits compliance with the provisions but also when circumvention is sought under different means. For instance, Article 13(6) DMA sets the standard of the gatekeeper’s non-compliance on the fact that the gatekeeper presents choices to end users in a “non-neutral manner, or by subverting (their) autonomy, decision-making, or free choice via the structure, design, function or manner of operation of a user interface”. Circling back to the disclosure templates proposed by Apple, neutrality does not seem to inspire the prompts that developers will have to display when the consumer completes a transaction on their alternative payment processing options since their main focus lies upon the fact that the app is not supported by Apple’s private and secure system. Furthermore, the prompt is not really necessary insofar as Apple plans to introduce new product page labels on the App Store informing users when an app they are downloading uses alternative payment processing through an information banner. The additional information will be subject to a new app review process to verify that those developers accurately communicate the information about the completion of their transactions that use alternative payment processors.

Alternatively, the argument can also be made that the strict requirements that developers must face to introduce alternative payment processing on their apps (authorisation, disclosure and fees on their content) are mainly aimed at steering them away from opting into the new business terms altogether. Despite that they, in theory, provide developers with a choice to enjoy a ‘more open and free’ experience for the distribution of their apps, it may well be true that overhead, transaction and overall costs may increase (rather than decrease) as a consequence of the change. Thus, business user autonomy is stripped from developers distributing apps on Apple’s devices, in violation of the terms of Article 13(6) DMA. Industry representatives have repeatedly raised this same point over the last few days (see here, here and here).

Third-party web browsers and browser engines: no Safari no cry

Outside of the optional business terms that developers may engage with, Apple also proposed changes with regard to the functioning of its designated CPS web browser Safari. Pre-DMA, end users could already easily uninstall the web browser from Apple’s devices and place competing web browsers as their default. For instance, Google paid Apple around $18 billion in 2021 to be Apple’s default search engine, even with detriment to Safari’s own position in search. The proposed changes expand on this uncharacteristic openness to complete compliance with Article 6(3) DMA: Apple will introduce a new choice screen that will surface when users first open Safari in iOS 17.4 or later prompting them to choose a default browser from a list of options of the main browsers available in their market.

Although Apple fundamentally disagrees with the measure, given that users will be “presented a screen before they have the opportunity to understand the options available to them”, the change will apply across the EU. Apple has not yet released how it intends to curate the list of options of the main browsers available, since different options have been juggled during the past few months on the number of browsers that should be displayed to consider that Article 6(3) DMA has been effectively addressed. For instance, to Alphabet’s proposal in September 2023 of a similar choice screen displaying five of the most popular browsers selected on the basis of their popularity in the region, industry players already disagreed that up to twelve different browsers should be listed.

Apple proposed a related measure enabling, once and for all, alternative browser engines other than WebKit (Apple’s proprietary engine) for dedicated browser apps and apps providing in-app browsing experience in the EU. Alike the previous technical measures that Apple will roll out starting in March, those browsers will follow authorisation by the ecosystem holder through dedicated authorisation processes for security reasons (Web Browser Engine Entitlement or the Embedded Browser Engine Entitlement for developers). The step is substantial for Apple insofar as, over the years, it had basically mandated third-party browsers to use its underlying browser engine WebKit that underpins Safari. This meant that rival browsers on iOS could not introduce a distinct software experience on their own web browsers because they depended on the same technology as that of Apple.

The change responds to the requirements of Article 6(4) DMA in enabling third-party apps (in this case, web browser apps) to be accessed by means other than those of the relevant CPS of the gatekeeper. It opens the door for rivals such as Alphabet’s Blink (it has been long preparing for this moment) and Firefox’s Gecko to introduce their browser engines into their apps relying on the iOS ecosystem so that they can become fully functional without any of the limitations that come along with the WebKit.

Notwithstanding, the proof of the pudding is in the eating and Apple’s changes in relation to Article 6(4) do not come without their amount of backlash. Apple has walled the garden of its proposed implementation of the DMA into the EU/EEA space in isolation. In other words, Apple will cater for its regulatory-driven solutions only in the EU, to the exclusion of its global strategy. To that end, it will cater its services into two different spaces: to the EU and to the rest of the world. For instance, a different version of the App Store will be designed for the EU and another one for the rest of the world. And this is precisely where the main criticism of the implemented changes surrounding the browser engines lies: in their territorial reach. Apple’s decision to (legitimately) apply those technical measures in the EU will indirectly force its competitors to do the same. The restrictions of WebKit running as the browser engine for their browser apps on iOS will prevail in the rest of the jurisdictions where they operate outside of the EU. For example, in the case of browser engines, Mozilla Firefox will have to maintain two separate browser implementations, which will pose an additional hurdle for them to operate in the market at a global scale. By extension, it seems like the ‘intended’ Brussels effect of the DMA will crumble beneath the regulatory framework’s feet.

Interoperability and data portability – every breath you take

Within Apple’s comprehensive plans to comply with the DMA, it did not forget to include technical measures to address the challenges arising from interoperability and data portability for developers, despite the fact that the consequences of the changes may fall foul of complying with the requirements set out under Articles 6(7) and 6(9) DMA.

On the side of data portability, Apple recognises to both end users and developers an expanded right to data portability. In principle, EU users will be able to retrieve data about their usage of their App Store and export it to the services catered by an authorised marketplace developer, in those cases where the developers of alternative marketplaces request their authorisation to retrieve and import these same data. Apple will provide access to the Account Data Transfer API for these requests and will provide additional information about the API entitlement request form in March. Even though the procedure meets the purpose of promoting contestability for business users in enabling end users to port their data across to alternative app stores, it falls short of meeting the enhanced thresholds posed by Article 6(9), which requires that the tools to facilitate the effective exercise of such data portability should include the provision of continuous and real-time access to such data.

On the side of interoperability, Apple has chosen to create a dedicated request form to provide interoperability with iOS and iPhone features on a case-by-case basis. Apple will act as a regulator within the process and will first decide whether the request falls within the scope of Article 6(7) and only when the response is positive then it will start to design a solution for effective interoperability with the requested feature. Then, Apple will create a tentative project plan following an initial assessment of the solution where Apple will determine whether it is feasible or not to design an effective interoperability solution or whether it is appropriate to do so in light of Article 6(7) DMA. If Apple decides that the solution is technically feasible, then it will develop the solution and notify when the interoperability request is addressed via a software update and by providing technical documentation to the developer. Although Apple has given detailed information on how the nitty-gritty of Article 6(7) will be descended into reality, one could say that generalised effects derived from interoperability solutions will not derive from its application. Instead, Apple proposes a one-to-one dedicated procedure per each developer’s request to capture their needs and potentially undermine their all-encompassing effects.

Key takeaways

Apple has been the first gatekeeper to propose a wide array of technical solutions to comply with different prohibitions and obligations that derive from the fast-approaching application of the DMA. They can be broken down into five main groups: i) the opening up of upstream app distribution at the marketplace level; ii) side-loading of apps; iii) the inclusion of alternative payment providers; iv) changes relating to web browser apps and engines; and v) dedicated solutions for orchestrating the DMA provisions around portability and interoperability. Not one of the changes that have been brought into the public discussion by Apple’s press release comes without its potential criticism (and exorbitant backlash from competitors), but now the ball stays in the European Commission’s court.

In my own mind, the following points of contention are the most salient in terms of their collision with the DMA’s spirit and provisions:

- The new fee structure should not act to the detriment of the competitive dynamics of the ecosystem on the side of developers, i.e., business users. If developers are worse off with the new cost structure fine-tuned by Apple and, thus, forced to stick with the prevailing business terms that already apply to them, the DMA will not permeate the ecosystem in levelling the playing field both at the upstream and downstream level of the distribution of apps.

- Apple’s proposed changes should be taken with a pinch of salt in terms of its prevailing power to rein in the decisions of its business and end users. Despite that the proposed solutions may seem in line with the ‘openness’ motto, Apple still holds strong powers to authorise, mediate and decide what business users make the cut for alternative distribution or for catering to alternative payment processing services.

- The DMA’s lack of the expected Brussels effect, prompted by Apple’s segmentation of its business strategy into a polarised environment (EU vis-à-vis non-EU) may cause more harm than good since business users will face additional costs of implementation and adaptation to the new business terms whilst they still bear the burden of distinct business terms worldwide.

In Breton’s own words, Apple can face ‘strong action’ from the European Commission if the App Store changes fall short of complying with the DMA. It is still too early to tell whether the European Commission will savagely enforce the DMA’s provisions from day 1 (i.e., 7 March 2024), but the demise of ecosystem orchestrators is nowhere near to be seen.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Competition Law Blog, please subscribe here.

Kluwer Competition Law

The 2022 Future Ready Lawyer survey showed that 79% of lawyers are coping with increased volume & complexity of information. Kluwer Competition Law enables you to make more informed decisions, more quickly from every preferred location. Are you, as a competition lawyer, ready for the future?

Learn how Kluwer Competition Law can support you.