* This entry is a re-post of the contributor’s CCM Blog post, find link here.

On 24 January 2023 the U.S. Department of Justice (‘DoJ’), joined by multiple U.S. States including California and New York, filed an antitrust lawsuit against Google alleging that the “industry behemoth […] has corrupted legitimate competition in the ad tech industry” (‘DoJ Complaint’) (para 4). The DoJ has charged Google with illegally monopolising the publisher ad server market, the ad exchange market, and the advertiser ad network market.

As a result of its anticompetitive practices, Google has gained pervasive power over the entire ad tech industry. One of Google’s advertising executives likened the situation in the ad tech sector to one in which “Goldman or Citibank owned the NYSE”. (para 6). The action brought by the DoJ follows after various States, led by Texas Attorney General Paxton, filed a very similar lawsuit against Google in December 2020 (‘State AGs Complaint’). The motion to dismiss brought by Google against the State AGs Complaint has largely been denied. The allegations in the DoJ Complaint overlap to a considerable extent with the State AGs Complaint. However, what makes the DoJ Complaint stand out is that the DoJ Complaint is seeking a structural remedy. More specifically, it seeks the divestiture by Google of the Google Ad Manager suite, including Google’s publisher ad server and Google’s ad exchange.

This blog post aims to provide a general understanding of the DoJ complaint. To that end, it will discuss the relevant ad tech sector, Google’s (alleged) anticompetitive behaviour and the sought-after remedy. In the end, this post will highlight the DoJ Complaint’s potential relevance for EU antitrust.

The Ad Tech Stack

The DoJ Complaint focuses on Google’s behaviour in the ad tech sector where Google acts as a middleman for and intermediate between website owners and advertisers in the process of selling and buying ad space on websites. Although the following will attempt to paint a picture of the ad tech sector, the picture will necessarily be general and simplified due to the sector’s complexity.

Website owners (so-called ‘publishers’) sell ad space on their websites to advertisers that are willing to buy these spaces and fill them with their (display) ads. The selling/buying of ad spaces by publishers and advertisers goes – in lightning speed – via a series of interactions between ad tech tools, which together make up the ‘Ad Tech Stack’.

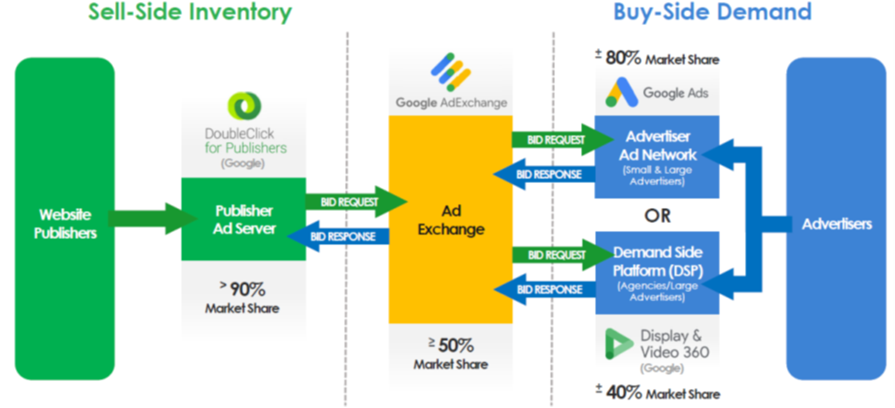

On the sell side, publishers make use of a ‘publisher ad server’ in order to manage their ad spaces and their online advertising sales. A publisher ad server evaluates potential ads from different advertising sources and determines which ad will be displayed to the user opening the website. Ad spaces are either sold directly or indirectly to advertisers. Whereas with the former the publisher deals directly with the advertiser, the latter sales are typically made via an ad exchange. This is a software platform that receives requests—often from a publisher ad server—to auction ad spaces. The ad exchange solicits bids on the ad spaces from advertisers (via so-called ‘advertiser buying tools’), chooses the winning bid, and transmits information on the winning bid back to the publisher ad server.

On the buy-side, just as publishers rely on publisher ad servers (as a middleman) to manage their ad space, advertisers use ‘ad buying tools’ to represent their interests. There are two sorts of ad-buying tools: ‘demand-side platforms’ and ‘advertiser ad networks’. Whilst the latter is used by both large and small advertisers, the former is used solely or predominantly by large advertisers (demand-side platforms are more complex and sophisticated).

According to the DoJ, Google is dominant on (all) three stages of the Ad Tech Stack, including the publisher ad servers, ad exchanges, and advertiser ad networks. Whereas on the publisher ad server market, Google’s DoubleClick for Publishers (‘DFP’) is the dominant force (90% market share), on the ad exchange market Google’s AdX holds a dominant position (50-90% market share). Both ad tech tools are part of Google’s Ad Manager suite. In the market for advertiser ad networks, Google Ads is the dominant company (80% market share). The DoJ does not find that Google’s demand-side-platform (Display & Video 360 or DV360) occupies a dominant position. This Google company nonetheless played an ancillary but nonetheless enabling, role in Google’s scheme to monopolise the Ad Tech Stack.

(The Ad Tech Stack, DoJ Complaint, p. 31)

Google’s alleged anticompetitive conduct

Google’s anticompetitive conduct consists of a series of interrelated and interdependent actions, which have had cumulative and synergistic anticompetitive effects (para 263). It would, however, be a Herculean task to summarise the DoJ’s description of Google’s anticompetitive conduct in a blog post (the same can be said about reading such a summary). Like the ad tech sector, the anti-competitive actions complained of are complex and technical. The aim here is thus to provide a general overview and stress particular aspects.

According to the DoJ, the overarching goal of Google’s conduct has been to force as many (especially high-value) transactions as possible to flow through its own ad tech products, with Google taking a cut of the advertising spend at each step of the way. The focal point of Google’s monetisation strategy has been its ad exchange, where it charges its highest revenue share fees. These have consistently been around 20%, while its rivals charged only a fraction of that amount (para 266). To that end, Google engaged in a multitude of actions (at least 10) that are together as well as individually branded anticompetitive (para 263).

The DoJ Complaint gives a comprehensive, detailed and chronological account of Google’s actions. It can be said, at a general level, that Google’s anticompetitive conduct includes acquisitions, ‘tying’ practices, preferential treatment by Google of its own ad tech products, manipulative practices, and the drawing up of restrictive platform rules.

Like the AGs Complaint, the DoJ Complaint alleges that Google’s anticompetitive actions include the illegal ‘tying’ of its ad network (Google Ads) to its ad exchange (AdX), which, in turn, Google tied to its publisher ad server (DFP) (by restricting the much needed ‘real-time access’ to AdX exclusively to DFP). Put differently, Google strung its ad tech products together.

Yet, the DoJ Complaint goes one step further compared to the AGs Complaint as it claims that the acquisition by Google of DoubleClick – through which Google gained a publisher ad server as well as an ad exchange – was anti-competitive. With the acquisition, Google was able to manoeuvre itself into a position that allowed it to eventually leverage its dominance on the ad network market to both the publisher ad server and ad exchange market. The DoJ also accuses Google of ‘killer acquisitions’. It claims that Google acquired AdMeld – a company which had developed a ‘yield management technology’ that posed a critical threat to Google’s ad exchange and publisher ad server businesses – in order to “extinguishing the leading innovator via acquisition” (para 145 ff).

Interestingly, the Federal Trade Commission decided at the time not to challenge the AdMeld and Google/DoubleClick acquisitions (the Commission similarly concluded that the Google/DoubleClick concentration would not significantly impede effective competition). The AGs Complaint already touched upon many of Google’s ‘manipulative’ practices.

However, the DoJ Complaint describes these in more detail. Remarkable in that respect is that the DoJ Complaint repeatedly notes that Google acted against the interests of its customers (e.g. paras 90, 92, 97, 132, 245). This includes Google’s ‘Poirot project’, an aspect that featured less prominently in the AGs Complaint (and yes, you are correct, it was named after Agatha Christie’s iconic master detective character, Hercule Poirot). Project Poirot entailed the manipulation by Google of the transactions that went through its demand-side platform to shift DV360 advertiser spending away from rival ad exchanges and towards AdX. (paras 215-230, particularly para 218). Through its anticompetitive behaviour, Google eventually hoped to build and defend a ‘moat’ around its ad tech products.

According to the DoJ, Google has distorted the competitive market forces that would otherwise determine prices and output and would incentivise innovation, efficiency, customer choice, and control (para 264). It is interesting to point out the role played by market forces that are regularly present in digital markets in relation to these anticompetitive effects. It follows from the DoJ Complaint that Google’s actions in combination with the characteristics of the relevant markets in the Ad Tech Stack – including economies of scale, network effects, data feedback loops, and lock-ins – caused Google’s anticompetitive conduct (even its earliest) to be lasting, enabling and amplifying the impact of subsequent conduct. It facilitated Google’s march to an ever-increasingly dominant position across the ad tech industry that persists today (para 264).

Break them up

An important aspect of the DoJ Complaint is the remedy. It asks the Virginia District Court to break up Google’s ad tech business. The DoJ requests the court to “[o]rder the divestiture of, at minimum, the Google Ad Manager suite, including both Google’s publisher ad server, DFP, and Google’s ad exchange, AdX, along with any additional structural relief as needed to cure any anticompetitive harm”. (para 342) A breakup may be a very effective remedy. Especially when the aim is to restore the competitive process and to prevent Google from (re-)engaging in similar anticompetitive conduct in the future.

Yet, breaking up a company is not a particular ‘light’ remedy and it is not granted often. In the U.S. no firm has been broken up since 1982 when AT&T was split into several distinct companies. What is more, the breaking up of a company for breaching the antitrust rules has only been requested once after AT&T when the DoJ sought divestitures in the Microsoft case. Although divestiture was initially granted by the Columbia District Court, this was overturned by the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals. Eventually, the DoJ abandoned the idea of a breakup and reached a settlement with Microsoft.

The request to split up Google’s ad tech business follows after discussions on breaking up Big Tech companies have flared up in recent years. However, the hurdle for attaining an order allowing the breakup of a company is considered rather high. For such a breakup the DoJ must, inter alia, establish a causal connection between the anticompetitive conduct and the dominant position. There must be sufficient evidence of a but for connection between anticompetitive conduct and the monopolisation of the market.

Implications for EU antitrust

The Commission is conducting its own investigation into a suspected breach of the EU antitrust rules with regard to Google’s behaviour in the ad tech sector. The fact that the DoJ is requesting divestiture of Google’s Ad Manager suit may embolden the Commission to do the same (possibly coordinating the remedy with the DoJ). The Commission is empowered to order structural remedies (art. 7 of Regulation 1/2003). Until now it has ordered divestiture only once in its ARA Foreclosure decision. Yet, that remedy was the result of an agreement between the infringing undertaking and the Commission.

Strictly speaking, the Commission has therefore yet to ‘unilaterally’ order divestiture. What is more, Regulation 1/2003 notes (Recital 12) that such remedies would only be proportionate where there is a substantial risk of a lasting or repeated infringement that derives from the very structure of the undertaking.

The DoJ Complaint, in this respect, points to Google’s pervasive conflicts of interest as it controls (i) the technology used by nearly every major website publisher to offer advertising space for sale; (ii) the leading tools used by advertisers to buy that advertising space; and (iii) the largest ad exchange that matches publishers with advertisers each time that ad space is sold (para 6).

It seems to follow from the DoJ Complaint that these conflicts of interest may have been the roots of Google’s multitude of anti-competitive actions. Leaving these conflicts of interest intact may give rise to the risk of future anticompetitive conduct. If one favours a divestiture remedy, one could argue that Goldman or Citibank owning the NYSE might be a risky situation indeed.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Competition Law Blog, please subscribe here.

Kluwer Competition Law

The 2022 Future Ready Lawyer survey showed that 79% of lawyers are coping with increased volume & complexity of information. Kluwer Competition Law enables you to make more informed decisions, more quickly from every preferred location. Are you, as a competition lawyer, ready for the future?

Learn how Kluwer Competition Law can support you.