The impressive acceleration in mergers and acquisitions, combined with the promotion of disruptive business strategies, has put the ‘regulatory gap’[1] paradox at the heart of the current European merger control policy debate. While the current EU merger control regime risks fragmentation with the advent of the new Guidance on Referral Mechanism and the Digital Markets Act (“DMA”) due to lack of legal certainty, Advocate General (“AG”) Kokott gave her opinion on the Towercast case (C-449/21) which can end the regulatory gap discussions or open the pandora’s box again. This blog post will bring forth the earlier interpretation of Article 21 EU Merger Regulation (“EUMR”) in the Member States and discuss whether Article 102 TFEU is a sufficient tool to bridge the so-called regulatory gap in EU Merger Control.

Background and Earlier Jurisprudence in the Member States

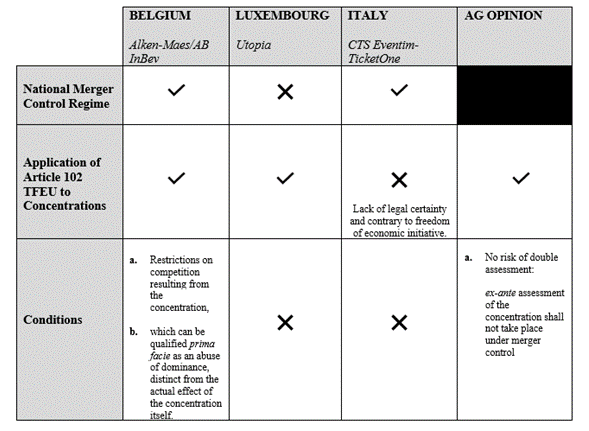

AG Juliane Kokott stated in her opinion that non-reportable concentrations which can avoid the ex-ante merger control assessment may be assessed ex-post under Article 102 TFEU (find a previous comment on the Opinion here). According to AG Kokott, Article 21(1) EUMR cannot preclude the application of Article 102 TFEU due to the hierarchy of norms and the principle of ex superior derogat legi inferiori (paras 30-38). Assessment of concentrations under Article 102 TFEU have also been questioned in some EU Member States. Perhaps due to the differences in merger control regimes, there is no consensus over the application of this tool to concentrations or under which circumstances it should be applied. While Belgium and Luxembourg Competition Authorities came to similar conclusions as AG Kokott and accepted the ex-post review possibility, the Italian Administrative Court (“TAR Lazio”), took a different approach.

Alken-Maes/AB InBev – Belgium

The acquisition of Belgium Brewery Bosteels by AB InBev set an important precedent in 2016. The competitor of AB InBev lodged a complaint to the Belgium Competition Authority claiming that the non-reportable acquisition infringed Article 102 TFEU and its corresponding provision in national merger control.

However, AB InBev argued that the enforcement power of Article 102 TFEU of national competition authorities derives from Regulation 1/2003, which is excluded from the scope of merger regulation via Article 21(1) EUMR. Thus, concentrations cannot be assessed under the abuse of dominance lens.

Similar to AG Kokott’s opinion, the Belgium Competition Authority and Brussels Court of Appeal held that concentrations which are not subject to merger control rules, can only be assessed by applying the provisions on abuse of a dominant position if the conduct is qualified as such prima facie and there are restrictions on competition which can be distinguishable from the mere effect of the concentration.[2]

Although this possibility is only admissible in exceptional circumstances and it was not the case in the acquisition at hand, this interpretation has been highly criticised. Considering that, as opposed to national courts, national competition authorities do not derive their competence to apply Article 102 TFEU from its direct effect, but from Regulation 1/2003 put in place in accordance with Article 103 TFEU.[3]

Utopia – Luxembourg

A decision on the assessment of concentrations under the prohibition of abuse of dominant position provision was issued in Luxembourg -the only EU Member State without a national merger control regime-. The Utopia judgement concerned a completed acquisition of a local cinema complex by a dominant cinema management company.

Similar to AG Kokott’s opinion, competition authorities tried to bridge the gap in the legislation via Article 102 TFEU. Thus, the Competition Council referred to the precedent Continental Can judgement and applied Article 102 TFEU in order to review the concentration at hand ex-post. In other words, if the concentration at hand does not reach the EUMR thresholds, the Luxembourg Competition Authority accepted that they could investigate the transaction under Article 102 TFEU, in the absence of national merger control. However, due to the failing firm defence, the Competition Council did not find anti-competitive effects in that specific case.

CTS Eventim-TicketOne Group – Italy

This year another decision came from TAR Lazio which annulled the Italian Competition Authority’s (“AGCM”) imposition of a fine on CTS Eventim- TicketOne Group for abusing its dominant position. One of the main conflicts in the case was TicketOne’s acquisition of four major national promoters.

However, this conduct was not assessed under EUMR or Italian merger control rules but under the abuse of dominant position by AGCM. Interestingly, TAR Lazio dismissed the assessment of concentrations pursuant to Article 102 TFEU and took a conflicting decision against AG Kokott’s new approach. According to TAR Lazio, competition authorities cannot assess a concentration under Article 102 TFEU or its equivalent in domestic law, considering that it would be against the principle of legal certainty and freedom of economic initiative to assess a concentration after clearance. TAR Lazio supported its view by also stating, Continental Can case law is no longer applicable since there is a specific regulation for merger control and Article 21(1) EUMR excludes the possibility of an ex-post review.

As observed from the case law, there is no agreement on the application of Article 102 TFEU to concentrations. This brings up the second subject, whether there is a vital and overdue need for a modification of the EU merger control regime or whether it is just ‘a solution in search of a problem’.

The Modification Needs of the EU Merger Control Regime

The logic behind the ex-ante merger control regime is enabling competition authorities to carry out an assessment beforehand to prevent any potential damage. However, there is no workable system of merger control which can capture every concentration capable of affecting competition.[4] As highlighted in many policy papers and AG Kokott, killer acquisitions[5] in big-pharma and big-tech industries and certain concentrations – such as the ones given above – are still able to escape from the merger control scrutiny of the EU. Although the EU has taken adequate steps (the new Guidance on Referral Mechanism and the DMA) to solve the remaining problem, will they also be effective? Another highly relevant question would be, is there actually a problem if we can assess these concentrations under Article 102 TFEU as AG Kokott suggests? Unfortunately, it might not be the most effective tool to review:

Firstly, the main aim of merger control is to create a mechanism to examine and possibly intervene in transactions that can create a dominant position. However, Article 102 TFEU can only apply to transactions where the acquirer is already in the dominant position. Perhaps, one might think that in that scenario the Referral Mechanism under Article 22 EUMR can be used. However, Article 22 which enables Member States to refer the acquisition to the Commission even if it does not meet the national or the EU notification thresholds has itself been criticized many times for diverging from core principles of the EU and endowing national competition authorities with excessive discretionary powers.

Additionally, AG Kokott asserts that the review possibility only exists when the ex-ante merger control is not possible. There is another uncertainty for situations where the relevant notifiable concentration is cleared under the national merger control rules in one Member State, would that prevent the possibility to review the transaction in another Member State under Article 102 TFEU?

Secondly, the debate also centres around the notification obligation, as it is another key aspect of the ex-ante merger control regimes. Considering that these transactions are not notifiable, catching these transactions and assessing them under Article 102 TFEU will be an ambitious pursuit. Thus, the main problem of not being notified will continue to exist.

Thirdly, as mentioned by TAR Lazio, this assessment possibility can be detrimental to legal certainty. Taking into consideration that the companies are left with the challenge of whether their mergers and acquisition will be reviewed ex-post after completing the transaction, as opposed to the strict time limits regulated under EUMR. For example, the Utopia acquisition took place in April 2013, and yet the decision came after three years in 2016. Moreover, if the merger at hand raises competition concerns, the fact is that it can be challenging to “unscramble the eggs”.

Fourthly, Article 14(1) DMA obliges gatekeepers to notify any concentration they perform, and the review possibility relies on the referral procedure. Now assessment can also be made pursuant to Article 102 TFEU. Nonetheless, non-gatekeepers and businesses operating in other sectors and non-dominant companies still face legal uncertainty. Considering that, even if the transaction is non-reportable both at the EU and national level, it can still be reviewed after clearance via Article 102 TFEU or Article 22 EUMR.

Fifthly, as stated by AG Kokott and national courts, Continental Can was an activist case law, aiming to bridge the gap when there was no merger control in the EU. Perhaps in situations such as the Utopia case, it can still be applicable. However, as highlighted by TAR Lazio, after the creation of detailed, lex specialis merger rules in every other Member State, is it really acceptable to use Article 102 TFEU to bridge the gap?

While the uncertainty remains pending an opinion by the European Court of Justice – since AG Kokott’s opinion is not binding- the jurisprudence and all the solutions discussed above reveal that inadequacies and enforcement gaps persist in hindering the effective application of merger control in the EU.

__________

[1] Regulatory gap refers to the discussions on the current EU merger control regime, whether it needs modification to prevent concentrations which are escaping from the merger control scrutiny or not.

[2] Brussels Court of Appeal, 2016/MR/2, 28 June 2017.

[3] Philippe Jonckheere, Alken-Maes/AB InBev (Bosteels) – A ‘Residual Jurisdiction’ for the Belgian Competition Authority to Assess Non-notifiable Mergers?.

[4] OECD, The concept of potential competition.

[5] Recent empirical and theoretical research in big-tech and big-pharma industries identified a trend for large incumbent firms to acquire start-ups with the sole purpose of eliminating potential competition, so-called killer acquisitions. See Cunningham, C., Ederer F.,Song, M., Killer Acquisitions.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Competition Law Blog, please subscribe here.

This blog post provides a comprehensive analysis of bridging the regulatory gap in EU merger control, focusing on the Towercast case (C-449/21) and comparing approaches across member states. It highlights the importance of harmonization and consistency in merger control processes. The comparison of different jurisdictions offers valuable insights for practitioners and policymakers. A well-researched and thought-provoking piece that contributes to the ongoing discussions on effective competition regulation in the EU.