The CJEU’s judgment in MEO earlier this year seemed to be a welcome, final piece of the puzzle in the legal framework for analyzing when price discrimination is abusive. It was now relatively settled, it seemed, that for price discrimination to be an abuse of dominance, it must generally fall into one of two boxes each providing its own, distinct test:

- If the concern is foreclosure of the dominant company’s own (upstream) competitors from the market (primary line discrimination), abuse is to be analysed through a price/cost test as the CJEU provided for in Post Danmark I.

- If, on the other hand, the theory of harm is distortion of (downstream) competition between two customers, then MEO holds that a substantial, competitive disadvantage upon one of the customers must be demonstrated based on ‘all the circumstances’.

In its decision imposing Royal Mail a fine of £50 million under Article 102 TFEU, Ofcom has blurred the lines between these two categories of pricing abuse. In what it calls a price discrimination ‘hybrid’, Ofcom applies MEO’s secondary line framework to behavior where the ultimate concern is primary line foreclosure.

Ofcom’s weighty 331-page decision that was rendered in August but only published in late October also contains a number of other notable points for practitioners, including on the role of the AEC-test post-Intel and on the significance of internal documents.

Royal Mail’s wrong-doing according to Ofcom

Ofcom found Royal Mail to be dominant in the market for bulk mail delivery in the UK with bulk mail comprising identical or similar letters sent in large quantities (for example bank statements, utility bills, and notices from local authorities).

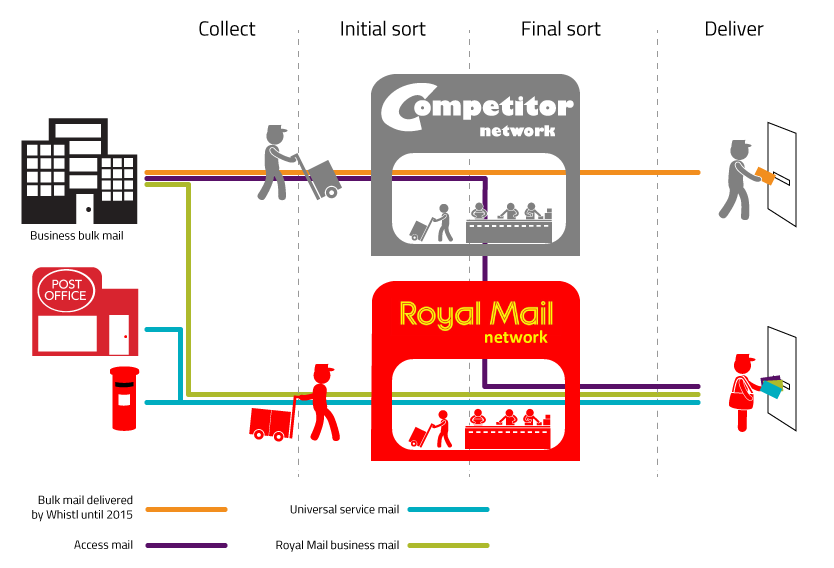

As illustrated in the figure below, the flow of bulk mail delivery comprises four stages: Collection, initial sorting, final sorting, and delivery. Only Royal Mail provides delivery to the whole of the UK, whereas a number of companies offer collection and sorting services. These companies serve as access operators in that they only offer end-to-end bulk mail delivery services to customers by making use of Royal Mail’s comprehensive delivery network. An access operator’s relationship with Royal Mail is thus somewhat similar to an MVNO’s relationship with an MNO within telecoms.

Whistl is one of these access operators. In 2012, Whistl made known that it intended to develop its own delivery infrastructure in certain areas of the UK in order to compete with Royal Mail on a complete stand-alone basis in these areas. Its long-term plans were to grow delivery operations gradually covering around 40% of all UK addresses by 2017 – thus still relying on Royal Mail’s network in the remaining areas.

In 2014, Royal Mail amended its wholesale prices towards access operators. The price changes involved different price plans for access operators depending on whether they were able to meet mail volume targets for areas covering the whole of the UK. According to Ofcom, this meant that access operators seeking to compete with Royal Mail by delivering letters in some parts of the country, as Whistl was, would have to pay higher prices in the remaining areas where it still made use of Royal Mail’s delivery network. Whistl ultimately decided to suspend its plans to extend delivery services to new areas.

Source: Ofcom

Ofcom found that Royal Mail’s price differentiation was abusive, as it discriminated access customers based on whether they were competing with Royal Mail on a stand-alone basis in certain areas. According to Ofcom, Royal Mail hereby placed access operators competing with Royal Mail at a competitive disadvantage relative to those who didn’t.

Classes of price discrimination cases are not exhaustive or closed

Ofcom makes very clear in the decision that it does not consider the primary/secondary line discrimination dichotomy to be governing or having much authority:

“We consider that the different categories or degrees of discrimination outlined above provide a helpful broad framework in which to consider the type of pricing conduct in issue and its effects. They are not exhaustive, however. It is important to note that the CJEU has not expressly endorsed or adopted this framework. Instead, the judgments of the CJEU focus on the application of an “in all the circumstances” test […] to assess whether the particular impugned conduct amounts to an abuse. […] The classes of abuse of dominance cases, including abusive pricing discrimination cases, are not closed.“

By stressing the importance of the established classes of discrimination being neither exhaustive nor closed, Ofcom hereby acknowledges that this case has a significant element of novelty. It will therefore be hard for Ofcom to argue on appeal that this case is not a clear candidate for a preliminary reference to the CJEU.

Is the price discrimination test in MEO applicable and suitable?

Heavily relying on the broad and open ‘all the circumstances’-test laid out in MEO, Ofcom acknowledges that to find abuse, it must demonstrate that the different prices are applied to equivalent transactions. Ofcom holds that the position of access operators that make use of their own delivery network in some areas is equivalent in all material aspects to access operators who do not. This is because, Ofcom says, that all access operators purchase the same service from Royal Mail by way of delivery of letters on the access operator’s behalf.

While this is true, Royal Mail’s provision of delivery services on behalf of access operators that use their own delivery infrastructure in certain areas does have some distinguishable features. Mainly, these access operators do not purchase the same scope or range of services – geographically speaking – from Royal Mail as access operators that are afforded the lower price do. Price cuts that are conditional on the customer purchasing a broader range or scope of services ought not to be considered against MEO’s discrimination framework. If so, all cases of price-based tying/bundling (mixed bundling) could in principle be challenged as discriminatory as the exact same product is priced differently depending on whether the product is purchased on a stand-alone basis or as part of a fuller range of products.

Importantly, the requirement of equivalence (where the authority bears the burden of proof) should not be conflated with the objective/cost-based justification defence (where the alleged offender bears the burden of proof).

It seems that Ofcom’s concern was essentially Royal Mail leveraging market power in non-contestable areas (i.e. areas where Whistl would not or was not about to establish delivery infrastructure) in order to ensure that Whistl did not place contestable demand with another (i.e. its own vertically integrated) delivery provider. This, however, does not seem to be a discrimination issue – at least not one that is analogous to the case in MEO.

The (lack of) significance of the AEC-test

Reiterating that the case is not one of pure primary line discrimination, Ofcom rejected Royal Mail’s argument that abuse must be determined based on a price/cost test, i.e. Post Danmark I.

Royal Mail submitted, in the alternative, that even if Ofcom is not required to carry out an AEC-test of its own motion (ex officio), Intel requires Ofcom to consider and assess as part of the body of evidence any AEC analysis submitted by Royal Mail. Ofcom’s consideration of the actual AEC analysis submitted by Royal Mail is very cursory as Ofcom mostly repeats the reasons why it does not consider an AEC-test to be relevant in the first place.

As for Ofcom’s comments that address Royal Mail’s submitted AEC analysis, two points are of particular note. Firstly, Ofcom takes issue with the analysis being based on Royal Mail’s own costs as the analysis, according to Ofcom, should be modelled on the costs of a potential new entrant. Secondly, Ofcom states that the analysis is unpersuasive as it was completed by Royal Mail after the event (ex post) and not as part of Royal Mail’s internal process leading up to the price changes.

These two assertions seem difficult to square with the CJEU’s clarification in Intel that – when presented with such evidence – the authority must assess the existence of a strategy aiming to exclude from the market competitors that are at least as efficient as the dominant company. More specifically, the AEC-test will by definition make use of the dominant company’s own costs as benchmark for how efficient the entrant must be. And although it is advisable for companies to carry out this assessment upfront, it ought to make no difference on the question of an infringement whether such an analysis is carried out after or before the event.

The overshadowing role of internal douments

Internal Royal Mail documents leading up to the decision on the price differential are extensively cited in the decision. When reading the decision, one is left with the impression that the internal documents has driven the investigation and serve as the main pillar of the decision with Ofcom holding that the elimination of Whistl was a deliberate strategy on the part of Royal Mail.

The Royal Mail case thus seems to share some common features with the European Commission’s decision in Qualcomm – at least as described in the Commission’s press release. In both cases, a price/cost test submitted as evidence by the company under investigation was rejected at least in part due to the overriding significance of internal documents.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Competition Law Blog, please subscribe here.

Kluwer Competition Law

The 2022 Future Ready Lawyer survey showed that 79% of lawyers are coping with increased volume & complexity of information. Kluwer Competition Law enables you to make more informed decisions, more quickly from every preferred location. Are you, as a competition lawyer, ready for the future?

Learn how Kluwer Competition Law can support you.

To be able to claim that there has been any price discrimination, there must be three necessary conditions. Firstly, the company will have a lower demand curve. It should be emphasized that there is no correlation between the degree of price discrimination and the extent of market power. Secondly, if different buyers have paid different prices, the situation may be considered in arbitration. Thirdly, a company seeking price discrimination must have a way how to get evaluations from consumers. Bashar H. Malkawi