Payment Systems in Turkey

Payment and Electronic Money Institutions are entities licensed to operate as a payment institutions or electronic money institutions pursuant to the Law No. 6493 on Payment and Securities Settlement Systems, Payment Services and Electronic Money Institutions (“Law No. 6493”) and the Regulation on Payment Services and Electronic Money Issuance and Payment Service Providers (“Payment Services Regulation”). Although the Law No. 6493 covers several types of payment services, the focus of this blog post is on the service that these entities provide as a payment facilitator (“PF”).

The Turkish Competition Board (the “Board”) considers PFs and banks to be competitors in the merchant acquiring market. While competing in this market renders the relationship between PFs and banks horizontal, the fact that PFs need access to the point-of-sale (“POS”) services provided by banks in order to operate in this market gives the relationship a vertical dimension as well. Hence, PFs are dependent on banks’ input to compete with banks in the merchant acquiring market. Therefore, the application of Law No. 4054 on the Protection of Competition (“Law No. 4054”) to the relationship between PFs and banks, as well as to the unilateral conduct of banks in relation to PFs, requires further consideration.

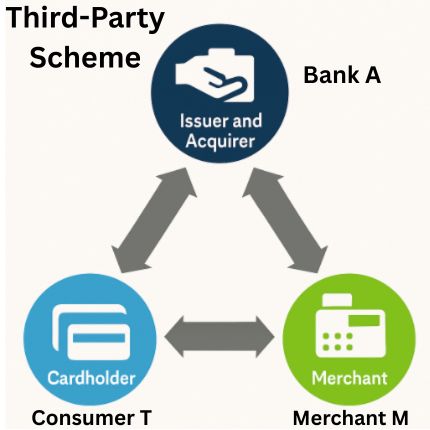

Before examining how PFs operate in more detail, it is useful to consider how the credit card market functions. The most straightforward scenario involves three parties: (i) the bank that issues and acquires the card; (ii) the merchant; and (iii) the consumer.

As shown above, the consumer (T) uses a credit card issued by bank (A) to make a purchase from merchant (M) who has a POS of bank (A). Since merchant (M) has a merchant agreement with bank (A), it has a POS of bank (A) and can accept payments made by cards issued by bank (A). Consumer T pays bank (A) the price of the purchased product, and Bank (A) pays merchant (M) the remaining of the price after taking its commission as per the agreement between merchant (M) and bank (A).

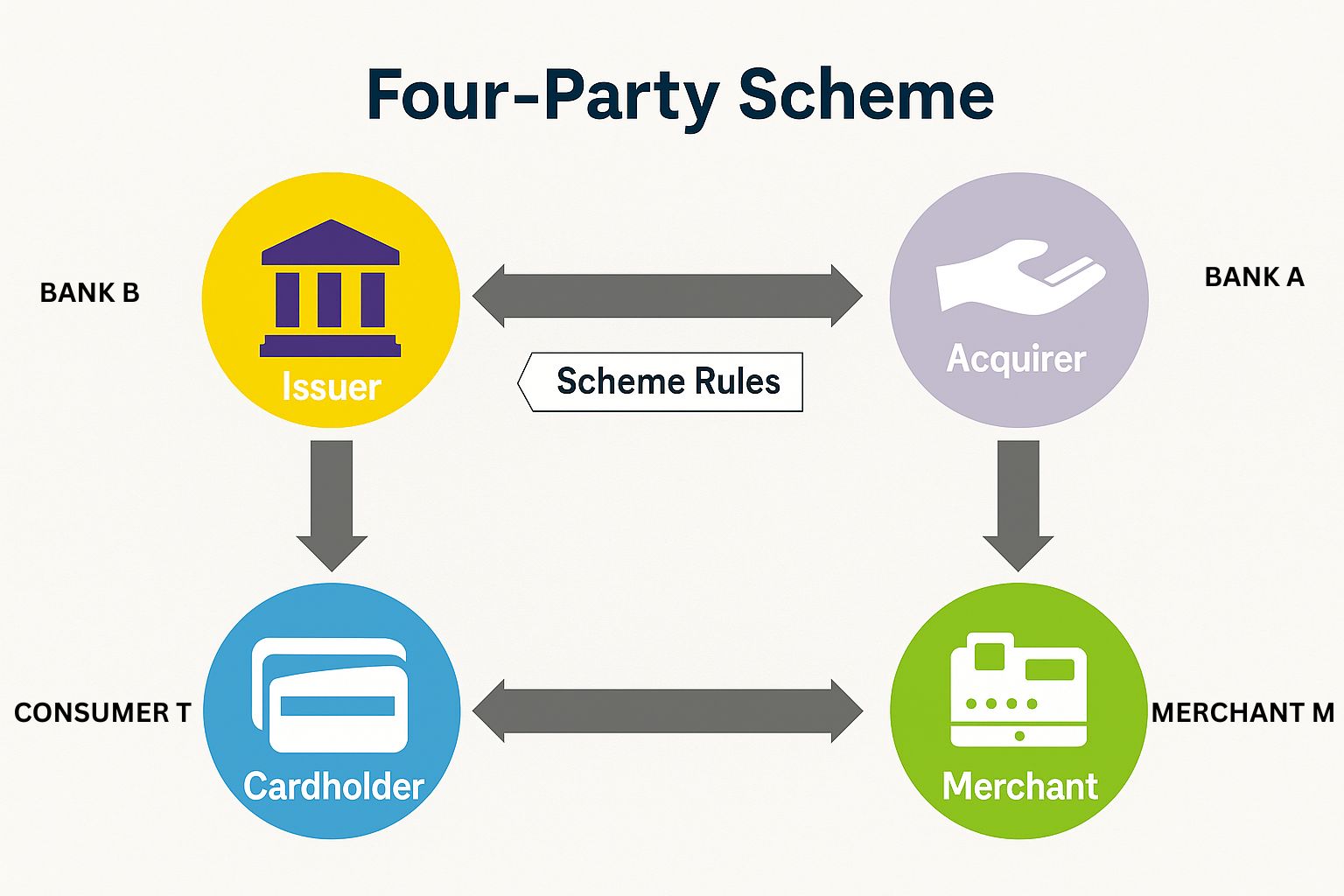

The second scenario is quite similar to the first scenario. The only difference is that the issuer and the acquirer banks are different. Therefore, two banks are involved in the second scenario.

As shown above, another bank intervenes to perform the clearing function in the second scenario. In this case, the consumer (T) uses the card issued by bank (B) to shop with merchant (M), who either does not have a merchant agreement with bank (B), or has one that is not economically viable. In addition to the above scenario, Bank B is also involved in the transaction. When T uses a credit card issued by Bank B to shop at the merchant’s store, the merchant may process the payment through Bank A’s POS. Banks A and B then proceed with the clearing and settlement process (assuming both banks are part of a settlement scheme such as BKM – Interbank Card Center).

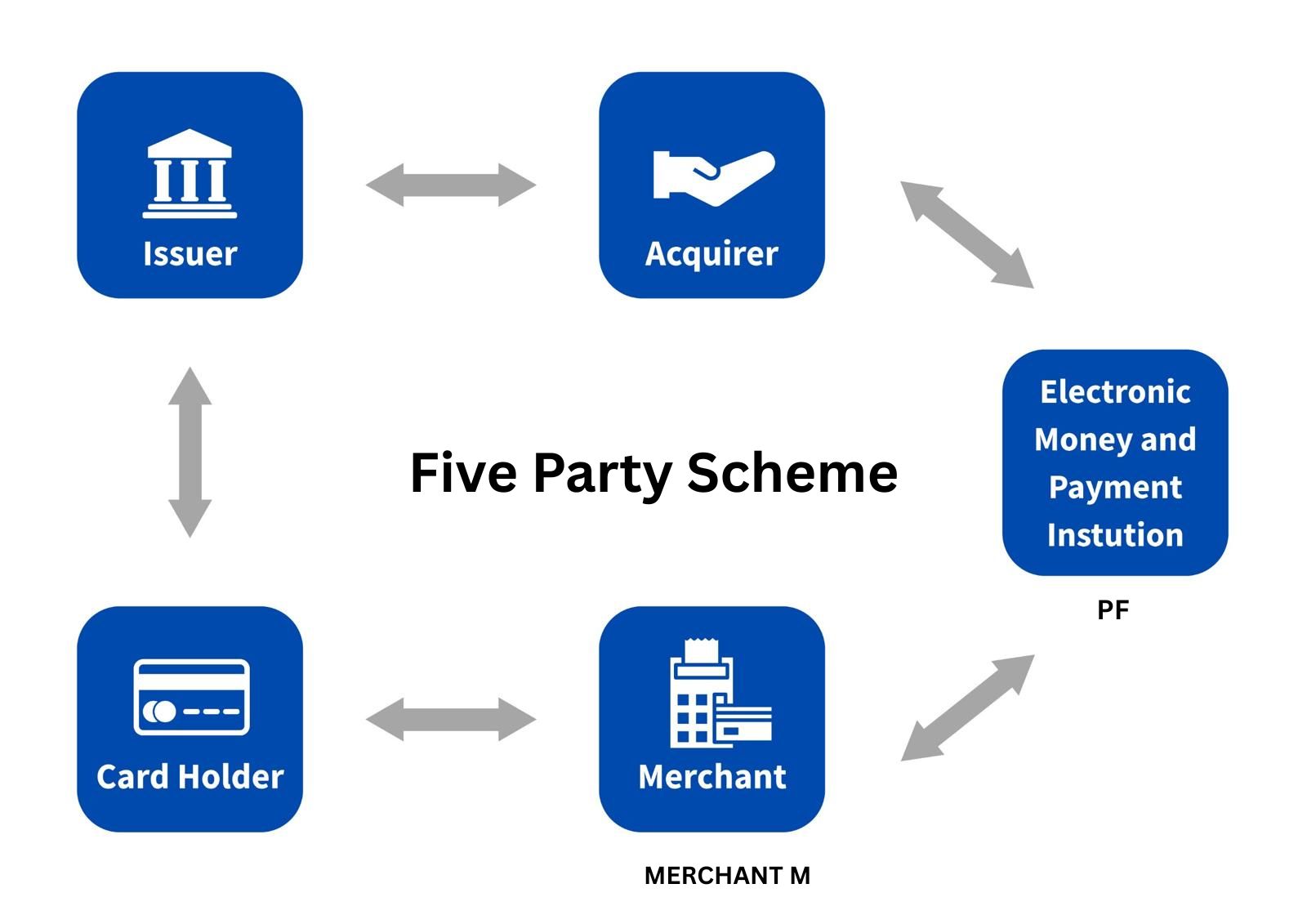

Both scenarios involve only banks. However, a PF can be involved in both the three-party and four-party scenarios. For a better understanding of the structure, we will include a PF in a four-party scheme. So, the third scenario is the case where a PF is involved in the second scenario.

As shown, merchant (M) receives a POS service from a PF. The PF may facilitate the acceptance of payments from merchants through agreements with banks.

The way PFs work is simple: A PF enters into agreements with different banks, integrates their POS services and provides an integrated POS solution to merchants. In other words, by contracting with various banks, a PF obtains access to these banks’ POS infrastructures and offers a catalysed service to merchants. It does so by creating its own physical or virtual POS system and enabling merchants to accept card payments from multiple banks through a single integrated interface. This means that, instead of negotiating and contracting with each bank individually and having separate POS devices, merchants can meet their POS needs by entering into an agreement with a single PF in a much simpler way. However, most PFs do not have an acquirer licence. Technically, this means that they cannot create their own virtual or physical POS devices. Nevertheless, what they are essentially doing is integrating the POS of different banks. PFs are permitted to do this without an acquirer licence.

When a merchant makes a sale, the card is directed to the PF’s service, which provides an integrated POS service, and the PF directs the card to the POS of the bank offering the most favourable commission. When a consumer makes a payment to a merchant, the PF can direct one-time (single) payments through the BKM clearing system to the bank that offers the most favourable price (this can be any bank within the BKM system). In other words, neither the merchant nor the PFs need a POS agreement with the bank that issued the card for one-time payments. Therefore, the BKM’s clearing and settlement arrangement facilitates inter-bank competition for single payments.

However, this does not apply to instalment payments. In principle, in order to accept such payments, the PF needs an agreement with the bank that issued the credit card. This gives the issuing bank a monopoly on acquiring instalment payments. In other words, a payment in instalments using a card issued by Bank A cannot be acquired at a Bank B’s POS. In principle, the issuing and acquiring banks must be the same bank for a payment in instalments. The only exception is credit card families where more than one bank has an agreement to issue and acquire the same branded credit card, such as Bonus and World.

Regulatory Framework

The Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey (“CBRT”) published the Payment Services Regulation in accordance with Law No. 6493. According to Article 8 of this Regulation, all payment service providers (“PSP”), including banks, payment institutions, and e-money institutions, are obliged to make their payment account services and payment infrastructure available to other PSPs upon request. In this context, banks that own the infrastructure must open their credit card POS access to all PSPs, including payment and e-money institutions that request it. The reverse is also true. Requests cannot be refused for any reason other than security, operational or technical requirements. Furthermore, discrimination among PSPs to which this service is provided is prohibited. PSPs are obliged to provide services to all PSPs that request them under similar conditions.

Pursuant to Article 8/2 of the Payment Services Regulation, the services provided must be comprehensive enough to enable the requesting PSP to carry out its desired activities within the scope of Law No. 6493 without any problems. In other words, when sharing this infrastructure with other PSPs, the PSP must provide it in a comprehensive manner to enable other PSPs to carry out their payment services without an issue. In this context, the PSP receiving the infrastructure must maintain a seamless service in order to compete effectively. Article 8 of the Regulation obliges the PSP to inform the requesting PSP of its decision within one month at the latest. This provision has been included in the legislation to prevent the requested bank from delaying the request for any reason other than the security, operational and technical requirements set out in the first paragraph.

To sum up, Article 8 of the Regulation on Payment Services identifies the market failure in three paragraphs and provides a comprehensive solution. The CBRT acknowledged that the market for payment services can only function if all PSPs share their infrastructure with each other. The purpose of this acceptance is to create multiple alternatives for each PSP and increase competition among these alternative channels. Not only does the provision impose an obligation to provide infrastructure, it also imposes an obligation to provide it to the extent that the requesting party can use it competitively.

So, what impact does this regulation have on competition law? Essentially, through this regulation, the CBRT, as the regulator of the relevant market, establishes that all PSP infrastructures are essential facilities for other PSPs. When drafting the legislation, the CBRT did not set any criteria for which PSPs are obliged to share infrastructure. In other words, although the CBRT could distinguish between PSPs with a market share or payment volume above a certain level, it has imposed this obligation on all PSPs regardless of these criteria. This regulation’s impact on competition law is that all infrastructures are defined as essential facilities for PSPs and, accordingly, as separate markets. Once this market definition has been established, it is necessary to assess whether the relevant bank’s actions fall under the category of refusal to contract, margin squeeze, or a different category of infringement. Therefore, the CBRT, the sector regulator, defines the border of the market through ex-ante regulation.

Conclusion

The PFs and banks compete in the merchant acquiring market (this is the market definition adopted by the TCB, see). In other words, merchants can receive POS services from either PFs or banks. For this reason, banks may be motivated to prevent the growth of PFs. There are two main reasons for this. Firstly, as the PFs enter into agreements with merchants who are existing or potential customers of the banks, the banks lose customers. This results in a loss of income for the banks. Secondly, the existence of PFs exerts competitive pressure on banks, who may be forced to reduce their prices (commission rates) for certain merchants. It is of course, not expected that banks would be content with the competitive pressure exerted by PFs. All these issues arise from competition in the merchant acquiring market.

Law No. 6493 and the CBRT’s Payment Services Regulation are both based on the fact and presumption that each credit card network (or brand partnership) is an indispensable commercial partner for PFs and merchants. Thus, one may think that each credit card network could be considered a separate market as PFs cannot compete (due to the portfolio effect) in the market without these products, especially card families such as Bonus and World. Without access to the POS of banks, particularly those with a stronger position, such as Bonus or World, they may quickly exit the market. Nevertheless, TCB’s current case-law suggest a wider market definition (i.e. the market for services related to instalment payments with credit cards and the market for services related to single payment with credit cards).

Furthermore, TCB has certain precedents where TCB consider the relationship with banks and PF as vertical thus consider the Vertical Block Exemption Communique numbered 2002/2 (“Turkish VBER”) as applicable. To put it another way, whereas the CBRT’s secondary legislation classifies the infrastructure of all PSPs as an essential facility, the Turkish VBER, which was issued by the TCB in 2002, permits providers (i.e. banks) that do not exceed a specified market share threshold (none of the banks can exceed the 30% threshold under the TCB’s current market definition) to impose non-competition obligations on buyers (i.e. PFs), as well as tying products and allocating exclusive customers (basically any restriction allowed as per Turkish VBER). It is evident that these two pieces of legislation are in direct opposition to one another, thereby engendering a substantial diminution of legal certainty. Consequently, it is reasonable to predict that the TCB may modify its jurisprudence on the definition of the market and the applicability of the Turkish VBER to the relationship between banks and PFs in the near future.

Lastly, in accordance with the prevailing market definition stipulated by the TCB, it is evident that no bank currently holds a dominant position within the industry. This complicates the application of competition law in intervening banks’ unilateral pricing behaviour. This indicates that even if banks consent to collaborate with PFs by providing necessary infrastructure, banks will retain the discretion to impose higher commission fees on PFs compared to merchants. This course of action, which is regarded as a standard margin squeeze within the context of competition law, cannot be addressed due to the absence of a dominant position. Therefore, it may be concluded that banks will be at liberty to increase the costs of their competitors in the merchant acquiring market. Yet, this will surely contradict with the Law No. 6493.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Competition Law Blog, please subscribe here.