In March 2025, Meta rolled out its AI assistant in Europe, which is accessible through its WhatsApp Messenger and will soon be available on Instagram and Facebook Messenger, too. The feature grants users of its platforms access to a “reliable and intelligent assistant” via a “new blue circle icon” on the apps. Trans-Atlantic observers may note that the launch comes almost a year after the same features launched in the United States, which, in Meta’s words, is a result of it having to “navigate [Europe’s] complex regulatory system”.

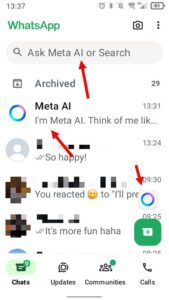

A screenshot showing the new AI Assistant integration in Meta’s WhatsApp Messenger.

Some commentators view Meta’s move as evidence of its “dynamic efficiencies” and “value creation”, made possible by the synergies originating from the 2014 Facebook/WhatsApp merger, which is now being leveraged in the intense “race of LLMs”. But, the firm’s decision to integrate its assistant directly into its consumer apps may, however, be of interest to competition regulators.

Indeed, the firm has been under intense competition law scrutiny as of late. This past Monday (April 17, 2025), Meta’s Mark Zuckerberg took the stand against the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which is seeking to break up Meta based on concerns that it excluded competitors as a result of its 2012 and 2014 acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp. The firm was also recently fined almost €800 million by the European Commission for integrating Facebook Marketplace into Facebook, a decision which it is appealing.

Given that everything is to play for in today’s AI market, competition authorities should be on high alert when it comes to looking for anti-competitive behaviour which could tip the market in favour of an incumbent, not least since experience shows that other digital markets have often ended up being dominated by a single firm. In this blog post, we consider whether Meta’s launch of its AI Assistant in WhatsApp could see it running afoul of competition law once again.

A Tying Case

Tying is a well-established abuse under Article 102 TFEU. It entails a firm making one product (the tying product) available only together with another product (the tied product). A long line of case law has established that four elements must be present in order for an abuse to be found. First, there must be two distinct products; second, the undertaking must be dominant in the market for the tying product; third, the undertaking must not give its customers a way to obtain the tying product without the tied product; and fourth, the tying must be capable of having exclusionary effects. Our view is that Meta’s recent AI assistant launch could satisfy each of these elements. Accordingly, we will briefly examine each.

First, as explained in the Commission’s recent draft guidelines on exclusionary abuse, it can be established that the tying and the tied products are two separate products if there is separate consumer demand for both. It seems highly plausible that WhatsApp and Meta’s AI Assistant have separate consumer demands, not least in light of AI assistants such as ChatGPT, Claude, or Le Chat, each of which offers a paid tier.

The second element, finding that Meta holds a dominant position through WhatsApp, depends principally on market definition, although it should be noted that the presence of network effects in social media markets may increase the likelihood that Meta may be found to hold a dominant position (as was the case in the Commission’s recent Facebook Marketplace decision).

The third element – that it must not be possible to obtain the tying product without the tied product – is the most interesting one. At the time of writing, it appears that Meta does not allow users to turn off its AI assistant from within its tying services, as has been reported in several news outlets. Although users of WhatsApp are not forced to use the AI assistant per se, the Commission has said in its Facebook Marketplace decision (paragraph 750) that “compulsion or coercion can still exist where the party accepting the tied product is not required to use it or is entitled to use the same product supplied by a competitor of the dominant undertaking”. Indeed – just as certain features of Facebook’s social network were exclusively available to its Marketplace product – only Meta’s own AI assistant is available through the AI button and search bar on WhatsApp. Once a consumer has interacted with the AI, it appears in the list of conversations, as shown in the image above.

The fourth element, that the conduct has exclusionary effects, could hinge on an argument that users would be less likely to use competing AI assistants from third-party providers (regardless of whether they multi-home or not). Such an argument could be buttressed by arguing that Meta could benefit from increasing returns to scale as a result of its conduct, while simultaneously denying that same scale to rivals, particularly with regard to accruing data on its users, which can be used to train its LLM.

This would be in line with a pattern of behaviour – first observed in programming forums – whereby users increasingly interact directly with LLMs inside a closed ecosystem, which forecloses valuable interactions that other undertakings seeking to develop competing LLMs could use to train on. For instance, platforms like Stack Overflow or Reddit have experienced a notable decline in activity, as many users now prefer to consult LLM-based tools such as ChatGPT. Unlike open forums, whose content constitutes “a collective digital public good due to their non-rivalrous and non-exclusionary nature”, which has historically been scraped and used as training data, closed platforms do not make their user interactions publicly accessible. This shift not only reduces the availability of high-quality, domain-specific training data in the public domain but also reinforces the advantage of incumbents who already operate at scale and can leverage proprietary data flows to improve their models.

A self-preferencing case

Another potential theory of harm is that Meta could have privileged its own AI assistant over those of rival firms, as occurred in Google Shopping. Such a theory of harm would require that other AI assistants be accessible over the WhatsApp user interface. As of today, it appears that this is not the case – just about. In fact, the infrastructure to supply an AI assistant over WhatsApp actually already exists; Meta offers business accounts, which allow other companies to communicate with customers via WhatsApp in order to offer promotions, provide customer service, share updates on order status, etc. These functions are increasingly powered by AI chatbots, and are surprisingly simple to set up, although we are not aware of any that are marketed as a general AI assistant.

If a competing AI assistant, such as ChatGPT, Claude, or Le Chat, were to launch on WhatsApp, then it would strengthen the case for self-preferencing. In light of the recent Android Auto decision – which widened the essential facilities doctrine, finding that not allowing competitors to utilise the dominant firm’s platform could constitute an abuse, so long as the infrastructure was intended to be open in the first place – Meta would likely not be able to deny rival undertakings from launching AI assistants on its platform, given that its business account infrastructure was built ‘with a view to enabling third-party undertakings to use it’. In other words, Meta would risk abusing its dominant position if it were to deny other providers of AI assistants access to the WhatsApp platform under its existing business account infrastructure.

Here, we already start to see the effects of Android Auto play out. At first glance, the ruling appears to encourage firms to create closed ecosystems, as it imposes a duty to deal on dominant firms to any infrastructure developed “with a view to enabling third-party undertakings to use it.” This is likely to give dominant firms pause when deciding whether to allow third-party undertakings access to their infrastructure.

However, a more dynamic and innovation-first perspective on competition yields a different set of incentives. Closed ecosystems are less likely to benefit from the complementarities arising when different firms contribute to value creation, since innovative firms may be excluded from participating. Indeed, ecosystems derive much of their value from third-party innovation, which depends on the extent to which third parties can access the infrastructure they need to innovate. For instance, the Android Auto ecosystem would be less valuable if third parties such as ENEL were not able to create apps for it. Opting for a closed ecosystem that relies exclusively on first-party infrastructure would mean that the dominant company must therefore shoulder the innovation costs for whatever products are built on that infrastructure. In the medium to long term, such ecosystems may struggle to compete with open, permissionless alternatives with greater possibilities for innovation.

Thus, the trade-off facing a dominant firm is not simply about access, but about the broader design of the ecosystem itself. On the one hand, an open ecosystem maximises the value of the ecosystem as a whole, yet limits the ability of the dominant firm to capture value within that ecosystem. On the other hand, a closed ecosystem maximises the dominant firm’s ability to capture value, yet forces it to bear the burden of more innovation costs, and may result in it losing out against a rival ecosystem which is more open and vibrant.

Potential Remedies

Our post has so far explored two theories of harm related to Meta’s recent practices: tying and self-preferencing. While finding Meta to be in violation of Article 102 TFEU would entail a deeper analysis, the post highlights some potential, real-life harms that may materialise if Meta does not change its approach. Accordingly, we make some suggestions, which need not involve large changes to Meta’s approach, but would protect the effective structure of competition and minimise harm to consumers, as well as reduce Meta’s risk of violating competition law in the EU or elsewhere.

First, the firm could avoid the third element of the above test by giving its consumers a way to opt-out of any AI integrations in its products and thereby allow users to obtain WhatsApp without its AI assistant being integrated. This may, however, lead to concerns that innovation would be harmed by the firm not being able to use AI in its products and offer that AI to its consumers in a convenient and accessible way.

Second, therefore, Meta could nullify the fourth element of the above test by allowing consumers to use competing AI assistants inside the WhatsApp UI. Given that much of the functionality already exists within WhatsApp, this could be surprisingly easy. WhatsApp could offer its AI assistant as a chatbot through the same interface that its business account customers use and then give its end consumers a choice of which AI ‘backend’ they would like to use. In that case, Meta would have to make a modest change to its WhatsApp interface, such that when consumers use AI-powered features, they would be taken to the AI assistant of their choice, perhaps one provided by a third-party firm, rather than Meta’s own AI assistant (similar remedies have been proposed for online advertising and content moderation).

This would let other AI assistants be offered via exactly the same interface to exactly the same users and therefore compete on a level playing field. Since this functionality for third-party integration with WhatsApp chats already exists, and users already interact with Meta’s AI assistant through the same chat interface, the technical burden on Meta would likely be extremely reasonable. This path forward would allow rival AI assistants to compete with Meta’s offering, while entailing low overhead costs in terms of implementing the remedy on Meta’s side and still retaining the benefits of AI assistant integration in WhatsApp.

It is worth noting that Meta’s rivals may not want to be intermediated by WhatsApp if Meta has access to data produced through consumers’ interactions with their LLMs through the WhatsApp platform. Given that digital markets are prone to tipping, rivals may be reluctant to allow Meta access to the chats produced with consumers, on which it may also be able to train its AI models and ultimately gain a competitive advantage. There is, however, a technical means to address this challenge, which is to simply ensure that any chats with third-party AI assistants have end-to-end encryption turned on, such that Meta could not view and train on the interactions with its competitors’ AI assistants. This would remove disincentives for rivals to offer their AI assistants through Meta’s interfaces and ensure a level playing field to facilitate competition on the merits.

Conclusion

In fast-moving digital markets, it is important to quickly identify potential abuses before anti-competitive harm can accumulate. In this blog post, we put forward a case that Meta’s choice to integrate its AI assistant directly into its social networks may harm competition in the adjacent AI assistant market. We considered whether such behaviour could constitute tying or self-preferencing under EU competition law and found that the possibility could indeed warrant further investigation, at least beyond what is possible within the scope of a blog post. Regardless, it would appear that there are several adjustments that Meta could proactively make to its current approach, which would help preserve the effective structure of competition – and give its consumers wider choice – and thus limit its exposure to competition law scrutiny.

____________________________

The author Todd Davies discloses that he was employed at Google as a software engineer between 2016 and 2022. All relations with the firm ended in March 2022.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Competition Law Blog, please subscribe here.