Fast and furious: that was the premise that would make the DMA’s enforcement effective. Overcompensating for past grievances in the application of Article 102 TFEU in the digital markets in terms of speed and remedies justifies the DMA’s need for having regulatory teeth. And teeth it has.

On 22 April 2025, the European Commission (EC) finalised its non-compliance procedures against gatekeepers Meta and Apple for DMA infringements. The enforcer imposed €200 million and €500 million fines, respectively. Both fines come one year and one month after their initial triggering by the enforcer through punitive proceedings aimed at curtailing (per se) anti-competitive conduct in their own tracks. Additionally, the enforcer also shaped the rest of its enforcement action via a number of press releases released on that same day. Transparency en bloc to counter the geopolitical tensions with the US, some would argue. This post considers both non-compliance decisions and the rest of the developments highlighted by the European Commission at the end of April.

Non-compliance procedures: nothing to see here, EDPB and Article 102 TFEU

The EC declared, for the first time in its history, that a gatekeeper infringes the DMA in some shape or form. Meta and Apple were the two winners of the DMA lottery for breaches of Article 5(2) and 5(4) DMA.

Meta’s pay or consent subscription model

Meta has been found to breach the prohibition on personal data combinations across first-party and third-party contexts under Article 5(2) DMA via the introduction of the pay or consent subscription model. In November 2023, anticipating the DMA’s impending application, Meta introduced its renowned pay or consent model on its Facebook and Instagram services in the EU, EEA, and Switzerland. The subscription model presented the user with a binary option: either the user chose to carry on navigating the social networks for free (the caveat being that consumer choice would be equated to granting consent in the sense of the GDPR) or the user chose to subscribe (for €9,99/month) to stop seeing personalised ads on Meta’s services.

Data protection authorities (DPAs) voiced their concern about the grave consequences introduced by such a model in terms of the risks posed to informational self-determination, despite the fact that news outlets and publishers streamlined them into the generation of revenue online. They were right to do so. Meta’s pay or consent model came as a response to previous findings from the Irish DPA that it could not rely on the legal bases of legitimate interest or contractual necessity to justify their processing of personal data for the purpose of delivering personalised advertising. DPAs had, therefore, proclaimed that consent as a legal basis was the only available legal venue to process personal data in this context.

Building on the research of data protection and privacy scholars, in my own view, this was not a satisfactory stance to take. The prevalence of consent within data protection frameworks points to a double fallacy: when users are asked to choose between a privacy and no-privacy scenario, they choose the latter; and when they make that choice, they are rational and fully informed economic agents. Although it might sound like a paternalistic viewpoint to defend, consumers do not read privacy statements in full (100-plus pages of fine print do not make the mark) nor can they, at times, understand them, due to their complexity. Shifting Meta’s available legal bases away from legitimate interest and contractual necessity and onto consent just misses the point, building on the misconstruction surrounding the ode of user consent.

Within this framework, Meta (as usual in its drafting of privacy policies) challenged the whole European data protection regime by considering fundamental rights to be alienable. That is, one can detach one’s fundamental right to the protection of one’s personal data in exchange for a price. The most extreme representation of such alienability points to the possibility of citizens selling their livers as a legitimate choice (let’s say, in exchange for a sum of money), whilst trading their fundamental right to physical integrity. In a less provocative proposal, Meta basically certifies the barter between a fundamental right and monetary compensation. In turn, the whole discussion also impacted the DMA regime in full, given that the prohibition under Article 5(2) can be simply lifted for those cases where gatekeepers can collect end user consent in the sense of Articles 4(11) and 7 DMA. By this token, if the GDPR regime does not sign off on the pay or consent subscription model, the DMA can rarely exempt the prohibition based on the same grounds.

The broader question arising from this interplay between regulations precisely stems from this illusory alienation among authorities. The DMA establishes under Recital 12 that it operates without prejudice to the GDPR. In principle, the European Commission is not dependent on the DPAs’ or EDPB’s opinions and decisions to secure a harmonised set of digital rules. Nor can the European Commission impose an interpretation of the GDPR on those authorities. The overlapping of authorities is quite unprecedented, and not covered by the Court of Justice’s Meta v. Bundeskartellamt ruling (Case C-252/21), since those cooperation and coordination mechanisms apply exclusively to EU competition law within a decentralised enforcement system where NCAs and DPAs can exchange information. In any case, within this latter set of cases, NCAs may still deviate from a DPA’s conclusions due to their autonomy in finding a breach of competition law. The same would seem to be true in this instance. In principle, the European Commission could deviate from the opinions and decisions of DPAs and the EDPB to the extent that consent in the DMA terms may not be equivalent to the GDPR’s protected values underlying a data subject’s granting of consent.

Despite the detachment of both pieces of regulation, the enforcer decided to replicate the EDPB’s Opinion 08/2024 on valid consent in the context of consent or pay models implemented by large online platforms. In the opinion, the EDPB basically declared that large online platforms (which, coincidentally, covers those types of economic agents designated as gatekeepers under the DMA, see para 28) implementing pay or consent subscription models will not, in most cases, comply with the requirements for valid consent if they confront users only with a binary choice between consenting to processing of personal data for behavioural advertising purposes and paying a fee.

Following this same line of thought, the EC establishes that Meta’s subscription model is not compliant with the DMA because: i) “it did not give users the required specific choice to opt for a service that uses less of their personal data but is otherwise equivalent to the ‘personalised’ ads service” (in the Opinion, for instance, in para 73); and ii) “it did not allow users to exercise their right to freely consent to the combination of their personal” (paras 67-71). In accordance with a wish to coordinate and cooperate with the EDPB, the EC’s stance in sanctioning this type of conduct via the DMA for these reasons is not particularly objectionable. That is, if the EDPB’s reasoning on pay or consent subscription models was impeccable (see comment here). Going back, once again, to the Court of Justice’s Meta v. Bundeskartellamt ruling, the connection of both arguments is much less apparent, since Meta’s proposed model builds directly on the CJEU’s backdoor statement that fee-based alternatives could still sustain the foundations of valid consent (para 150 of the ruling).

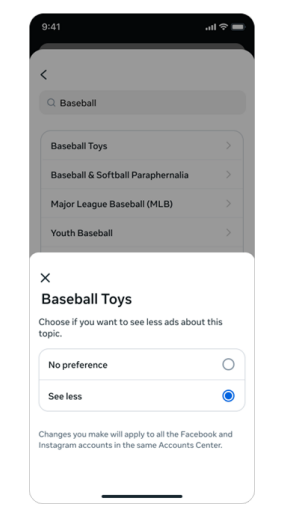

Against this background, the European Commission decided to impose a €200 million fine on Meta. However, the fine only covers March 2024 to November 2024. By November 2024, Meta introduced another version of the free personalised ads model, offering a new option that allegedly uses less personal data to display advertisements. According to Meta on its latest compliance report, users in the EU who choose the ‘free’ version of the subscription model will be able to choose to see ‘less personalised ads’ (page 21 of the compliance report). For instance, let’s imagine that a user prefers to see behavioural ads on the social network of certain categories (e.g., the wider category of baseball). From the vast interests comprised under the baseball category, the user can simply choose the ‘see less’ option for particular aspects of baseball (e.g., baseball toys) by opting out of the processing of personal data individually through a toggle, as shown in the image below:

The European Commission is currently assessing whether the slight change introduced by Meta meets the regulatory requirements set out in Article 5(2) DMA. In my own view, if the EC is going to take the case with all seriousness and make the EDPB’s reasoning good, there is a great chance that Meta will face further challenges from the enforcer. Due to the contingent nature of the newly-released features (that the EC has not yet assessed under the lens of Article 5(2) DMA), the non-compliance decision issued against Meta does not fare well against the requirements of Article 29 DMA. At face value, Article 29(5) DMA reads that “in the non-compliance decision, the Commission shall order the gatekeeper to cease and desist with the non-compliance within an appropriate deadline and to provide explanations on how it plans to comply with that decision”. As opposed to its non-compliance decision against Apple for its breach of Article 5(4) DMA, the EC’s non-compliance decision is incomplete, since it does not declare the cessation and desisting of Meta’s unlawful conduct. End result? The pay or consent subscription model will have to be removed by Meta at some point in time, but not within the 60 day-deadline that the enforcer has set out for Apple to comply with. Bottom line: the EC’s non-compliance decision will have to be complemented with further enforcement action, either via the issuing of a new non-compliance decision (fast and furious, no more) or by amending the recently issued non-compliance decision. Given that Article 5(2) cannot be subject to specification proceedings under Article 8(2), there is no scope for those implementation measures to be ‘formally’ imposed by the European Commission via non-punitive means.

Apple’s steering of users: Article 102 TFEU 2.0

The European Commission also fined Apple €500 million for infringing the steering provision under Article 5(4) DMA. The provision reads that “the gatekeeper shall allow business users, free of charge, to communicate and promote offers, including under different conditions, to end users acquired via its core platform service or through other channels, and to conclude contracts with those end users, regardless of whether, for that purpose, they use the core platform services of the gatekeeper”. In short, anti-steering provisions cannot longer be enforced by Apple on its iOS and, additionally, it must actively put forward technical implementations to make that possible.

Apple’s 2024 compliance report was mute on the subject. The 2025 version of the compliance report was not much better, despite that the gatekeeper had de facto in August 2024, proposed changes to the ability of developers to perform steering.

As per the proposal, Apple enables app developers who have opted into the new terms and conditions generated ex profeso for European developers as a consequence of the DMA to steer users under certain circumstances. First, they are subject to a number of recurring fees when they manage to steer users. Those fees went up to 17% in their first pitch to the European Commission, at the time that the non-compliance procedure was triggered. By August 2024, steering ignited a 5% initial acquisition fee (for the acquisition of an end user from the App Store) on the sales of digital goods and services occurring within a 12-month period after the initial install and an additional 10% store services fee on the purchases made via the link-outs.

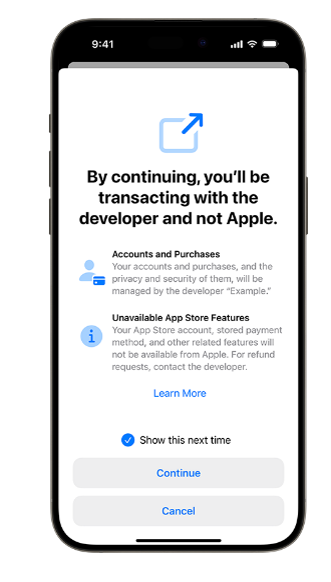

Second, Apple imposed upon developers to show an in-app disclosure sheet when taking users to their destination using an actionable link, as shown in the image below:

Apple also restricted the in-app prompt’s format and style as well as the moment when it should be issued within the end user’s experience. By doing that, developers were discouraged from performing steering and, even in the cases where they did, consumers ended up being discouraged through the ‘scare screen’ alerting them of the fact that their privacy and security would be managed by the developers, and not by Apple directly.

In this context, the European Commission found that Apple failed to comply with Article 5(4) DMA not due to the way by which it complied with the provision, but rather through the restrictions it imposed by doing so that, in the end, result in “consumers (not) fully benefit(ting) from alternative and cheaper offers as Apple prevents app developers from directly informing consumers of such offers”. On top of that, the European Commission declared that Apple had “failed to demonstrate that these restrictions are objectively necessary and proportionate”. Unlike Meta’s case, the EC does order through the issuing of the non-compliance decision to “remove the technical and commercial restrictions on steering and to refrain from perpetuating the non-compliant conduct in the future, which includes adopting conduct with an equivalent object or effect”.

Recital 40 DMA fleshes out the possibilities open to a gatekeeper when implementing the steering technical implementations under Article 5(4) DMA. In theory, gatekeepers can (and do) monetise the direct or indirect remuneration by the business users for facilitating the initial acquisition of the end user by the business user. As a matter of fact, EC officials have reiterated that the “free of charge” clause under Article 5(4) DMA does not necessarily entail that steering possibilities must be provided at zero cost to the business users. From what one can guess from the press release, it seems that two separate and recurrent fees do not abide by this premise or, at least, that the 10% store services fee does not fall under the scope of the gatekeeper’s capacity to be remunerated for a developer’s initial acquisition of end users from its app store. In a parallel non-compliance procedure opened by the European Commission, Google faces similar allegations relating to its imposition of recurrent fees and restrictions on developers for monetising its Google Play services. The Court of Justice’s recent Android Auto ruling (Case C-233/23) also points to the fact that dominant undertakings (let’s say, gatekeepers) are not necessarily precluded from requiring an appropriate financial contribution from the undertaking that requests interoperability (in this case, the developer steering end users). Such contribution must stay as fair and proportionate, having regard to the actual cost of such development, to derive an appropriate benefit from it (para 76 of the ruling). Perhaps the European Commission disagrees with Apple’s approach because the 5% initial acquisition fee does not seem to be proportionate, because it does not correspond with the actual cost of such implementation, although it can, in fact, exist in a more reduced fashion. If this is the discussion that gatekeepers v. Commission are having relating to those provisions which explicitly flesh out that they must be provided “free of charge”, one also starts to wonder whether each of the DMA implementations could, potentially, be exercised by business users in exchange for a fair and proportionate remuneration to the gatekeeper.

On a more provocative note, there is no indication under Article 5(4) DMA that the gatekeeper must justify that its implementation of the steering provision should be necessary and proportionate. The DMA explicitly requires the proportionality test to be applied for Articles 6(11), 6(12) or 6(7), whereas those same requirements are not entirely clear under the steering mandate. Despite that the regulation does not include such proportionality test, the Compliance Template Form (discussed in depth here) requires gatekeepers to disclose what actions it has taken to protect, integrity, security, or privacy to comply with the provision and why these measures are strictly necessary and justified and there are no less restrictive means to achieve these goals (Section 2.1.2.m) of the Compliance Template Form). The enforcer has introduced such necessity and proportionality tests through the back door, so to speak. The EC’s fine on Apple just demonstrates the first step in enlarging the DMA’s contours.

23 core platform services, browser choice screens and a new set of preliminary findings

Fine imposing is always shinier for enforcers. However, the EC issued three additional developments to its roster of on-going enforcement actions surrounding the DMA.

The first one corresponds to its closing of the non-compliance procedure against Apple for its compliance with Article 6(3) DMA relating to the default settings regarding browsers, search engines, and other features, following Article 29(7) DMA. Despite the EC being quite concerned in March 2024 about Apple’s uneven compliance with the provision, the gatekeeper’s further changes on its compliance have satisfied the EC’s appetite for effective enforcement. In August and October 2024, the gatekeeper amended the choice screens for browsers and search engines to be displayed on iOS devices and also made a wide range of its legacy apps (such as Safari, Camera, or the App Store) deletable by users through a centralised default control centre embedded in its settings.

The second development that took place on that same day relates to the EC’s non-compliance procedure relating to Article 6(4) DMA. That is, the provision compelling Apple to open alternative app and app store distribution on iOS services. The EC triggered the non-compliance procedure in June 2024 for a wide range of reasons, including Apple’s imposition of its 0,5€/download Core Technology Fee on third-party app marketplace providers and app developers. The European Commission has put pen to paper and issued its preliminary findings to the gatekeeper, opening the possibility for the non-compliance decision to be issued later this year.

Bearing in mind those two developments relating to the enforcer’s ongoing non-compliance procedures, the cases against the gatekeepers remain as follows from the table below:

| Gatekeeper and CPS | Provision | Phase of proceedings |

| Meta (Facebook and Instagram). | Article 5(2) DMA. | Fine imposed on 22 April 2025 (and pending findings on new features). |

| Apple (App Store). | Article 5(4) DMA. | Fine imposed on 22 April 2025 (and 60 days to comply with cease-and-desist order). |

| Apple (iOS). | Article 6(3) DMA. | Closed non-compliance procedure on 22 April 2025. |

| Alphabet (Google Play). | Article 5(4) DMA. | Preliminary findings issued on 19 March 2025. |

| Apple (iOS). | Article 6(4) DMA. | Preliminary findings issued on 22 April 2025. |

| Alphabet (Google Search). | Article 6(5) DMA. | Preliminary findings issued on 19 March 2025. |

| Apple (iOS and iPadOS). | Article 6(7) DMA. | Implementation measures imposed on 19 March 2025. |

Finally, the EC also reduced the DMA’s scope by de-designating the first CPS of its history: Facebook Marketplace. As of 22 March 2025, Facebook Marketplace is no longer captured by the CPS as a standalone nor integrated within Facebook’s wider service. As the European Commission declared, abiding by the procedure under Article 4(1) DMA, Meta requested the EC on 5 March 2024 “to reconsider the designation of Marketplace”. After a whole year of reconsidering Facebook Marketplace’s situation, the EC comes to the conclusion that it “no longer meets the relevant threshold giving rise to a presumption that Marketplace is an important gateway for business users to reach end user”. If anything, the development is a delayed rebuttal of the quantitative presumption applied to Facebook Marketplace back in September 2023, where the EC stressed that the service did surpass the thresholds by far and, thus, would merit DMA designation.

On the designation decision, the EC went to great lengths to demonstrate that there were, in fact, any business users within the service, since Facebook had hampered businesses from publishing listings on their professional profiles since January 2023 (para 239 of the designation decision). To the end of estimating the service’s yearly active business users, the EC took recourse to the best approximation possible: it would only consider Facebook business pages with one or more listings on service as well as users, established or located in the Union, who had created 28 or more listings in at least one month of the financial year, with 80% or more listings being made in the same category (para 277). By doing so, the EC highlighted that the “figure largely exceeds by a factor of more than 5-10 yearly active business user threshold, even without factoring in the number of Facebook business pages with one or more listing on Marketplace” (para 278). In other words, the end users factored as business users for the purposes of estimating Marketplace’s yearly active business users surpassed by far the number of actual business users present in the service. Meta’s appeal to the designation decision questioned such an approximation. The hearing of the appeal is set to be held the next 15 May, so the European Commission decided to backpedal its approach before its estimations were questioned directly by the General Court.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Competition Law Blog, please subscribe here.