Time present and time past

Are both perhaps present in time future,

And time future contained in time past.

From T. S. Eliot, Four Quartets

Establishing an antitrust infringement can already be an arduous task. Yet, effective antitrust enforcement increasingly requires designing remedies that go above and beyond just prohibiting the infringing behaviour. This development engenders a crucial question: how effective have antitrust remedies actually been?

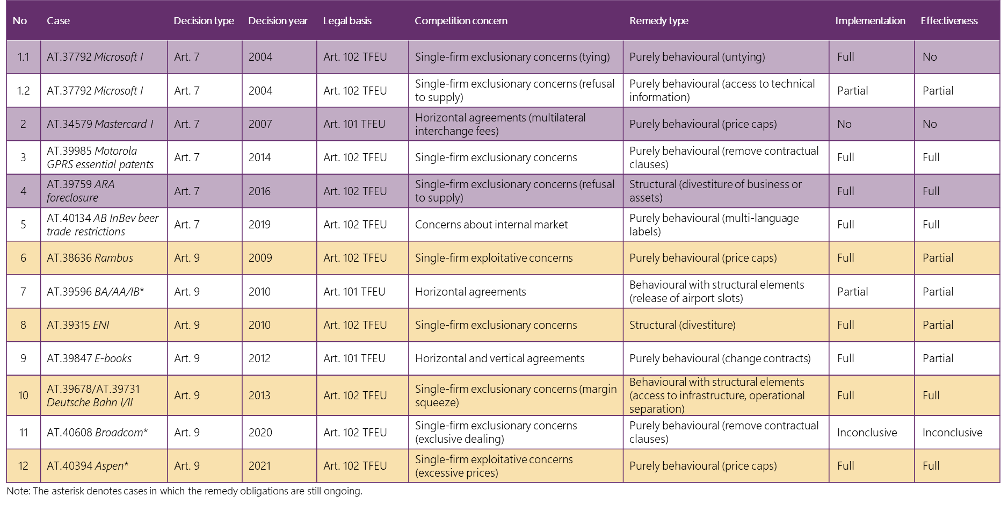

In a study that we recently coauthored for DG COMP, as part of a multi-disciplinary consortium led by law firm Grimaldi Alliance and economic consulting firm NERA, and including monitoring trustee Thomas Hoehn, we addressed this question by: (i) constructing a novel dataset of all non-cartel antitrust decisions that the European Commission adopted between 24 January 2003 (entry into force of Regulation 1/2003) and 31 December 2022; (ii) retrospectively evaluating a carefully selected sample of twelve significant decisions, based on interviews with case teams, decision addressees, and market participants; and (iii) interviewing enforcers from multiple jurisdictions, scholars, and practitioners on the challenges and best practices of antitrust remedies.

Context to the Study

Retrospective evaluation is key for the effective enforcement of competition law (see in this sense also the Draghi Report’s proposal 8 for revamping competition; see also the volume on the EU experience edited by Ilzkovitz and Dierx, 2020). Yet, while the practice of EU merger remedies has been systematically evaluated before (starting with the Commission’s merger remedies study of 2005), ours is the first study to turn the attention in the same way to the sparser and more heterogeneous practice of EU antitrust remedies. Accordingly, while merger remedies can already benefit from substantive guidance (through the Commission’s merger remedies notice), no comparable guidance is available yet on antitrust remedies.

Antitrust remedies in the EU are governed by Regulation 1/2003, whose Art. 7 (prohibition decisions) foresees that the Commission can impose on the undertakings that have violated Art. 101 TFEU (restrictive agreements) or Art. 102 TFEU (abuse of a dominant position) “any behavioural or structural remedies which are proportionate to the infringement committed and necessary to bring the infringement effectively to an end”. Alternatively, Art. 9 (commitments decisions) foresees that the Commission may make binding on undertakings commitments that “meet the concerns expressed to them by the Commission in its preliminary assessment” (on remedies in EU competition law more broadly, see the volume edited by Gerard and Komninos, 2020). On the occasion of its twentieth anniversary, Regulation 1/2003 recently underwent a health check, and our study also provides recommendations on how the Commission’s practice and policy of antitrust remedies could be improved under a possible update of the legal framework.

While there is some disagreement in the literature on what exactly it means to bring an infringement effectively to an end (see, for example, the different views expressed by Ritter, 2016, and Ibáñez Colomo, forthcoming), we can think of the objective of antitrust remedies as being to stop the infringing behaviour, to prevent its repetition and the circumvention of its prohibition, and to remove its anticompetitive effects. Depending on market conditions, the behaviour at issue, and the timeliness of antitrust intervention, the three constituent parts of this objective may coincide. Regarding the said third constituent part, the literature also talks about restorative remedies, although the expression “restoring competition” is only a recent import into EU law (see recital 37 of the ECN+ Directive) from the US (see the judgment of the Supreme Court, United States v Grinnell Corp.).

It is against the standard of the remedies’ intended objective in the relevant Commission decision that in our study we assess their effectiveness. When the objective of a remedy is limited to stopping the infringing behaviour, effectiveness of a remedy follows straight from its implementation. When the objective of a remedy goes beyond that, effectiveness may be hampered by remedy design flaws. Broader measures of effectiveness include the impact that the remedies had on the markets concerned by the infringement, and the influence that the decisions containing them had on subsequent guidance, jurisprudence, and sector regulation.

As with the evaluation of merger remedies, with the evaluation of antitrust remedies it can be challenging to distinguish between the lack of competitive effects of the transaction/behaviour and the effects of its remedies. With antitrust remedies comes the additional challenge of distinguishing between the effects of the “cease-and-desist order” that is always part of a prohibition decision and the effects of the (positive) remedies.

Notable findings of the Study

Findings based on the decision dataset

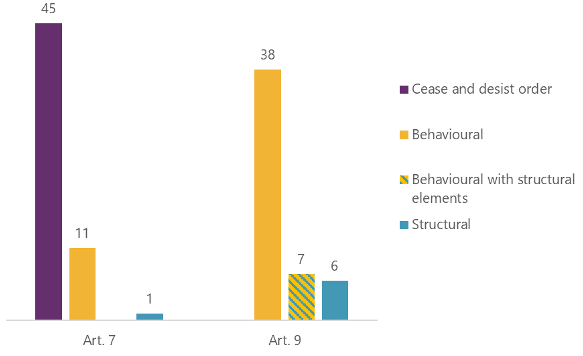

Drawing from, primarily, the Commission’s COMP Case Search website, we constructed a novel, comprehensive and detailed dataset of all non-cartel antitrust decisions taken by the Commission between 24 January 2003 and 31 December 2022. We counted in total 108 decisions, split between 57 Art. 7 decisions and 51 Art. 9 decisions. Since Regulation 1/2003 only started to apply on 1 May 2004, this includes a handful of decisions still taken under the preceding Regulation 17/1962, among which is the well-known Microsoft I decision.

Based on a textual analysis of the decision, we first categorised the competition concern in each decision, distinguishing between horizontal agreements, vertical agreements, single-firm exclusionary behaviour, single-firm exploitative behaviour, and concerns related to the single market. We then categorised the remedy, distinguishing between behavioural remedies (such as the obligation to change contractual clauses), structural remedies (such as the divestiture of assets), and behavioural remedies with structural elements (such as the transfer of airport slots).

Among other results, we found that about 80% of Art. 7 decisions are simple cease-and-desist orders, where basic orders have been replaced over time by “like object or effect” orders that, in addition, require the concerned undertakings to “refrain from repeating […] any act or conduct having the same or equivalent object or effect” (see for example Art. 3 of the Slovak Telekom decision). In only one of the twelve remaining Art. 7 decisions was a structural remedy imposed, namely in the ARA foreclosure decision, which followed the cooperation procedure.

While purely behavioural remedies are the most prevalent remedy type also under Art. 9, structural remedies were accepted in six cases – all related to energy markets – and behavioural remedies with structural elements were accepted in seven more cases.

To enhance compliance, remedy packages can include flanking measures such as reporting obligations and the appointment of a monitoring trustee. No monitoring trustee has been appointed in an Art. 7 case since Microsoft I, where the delegation of investigative powers to the monitoring trustee and the obligation of the concerned undertaking to pay for its services was ruled to be unlawful by the General Court. In Art. 9 cases, monitoring trustees have been appointed in about a half of the purely behavioural cases, in the vast majority of the behavioural cases with structural elements, and in all structural cases.

Findings based on the case studies

From this universe of cases, in our study we select respectively five Art. 7 and seven Art. 9 cases as the basis for the ex post evaluation of remedy implementation and effectiveness. After excluding simple cease-and-desist orders, as well as decisions under judicial review at the time of the case selection (Google Search (Shopping), Google Android, International Skating Union’s Eligibility Rules and Google Search (AdSense)) and decisions fully or partly annulled (CISAC Agreement), we found it straightforward to select the five most important of the remaining seven Art. 7 cases. To select the seven most important of the 49 Art. 9 cases remaining after excluding Upstream gas supplies in Central and Eastern Europe (under review at the time of selection) and Cross-border access to pay-TV (annulled by the Court of Justice), we ranked the cases based on a quantitative index combining a range of factors, including the length of the decision and the number of downloads of the decision from the Commission’s COMP Case Search website. We then selected the highest-ranking ones, whilst taking care to ensure coverage over time, legal basis, type of competition concern, and type of remedy.

The case studies aimed to elicit the extent to which remedies in the individual case were implemented by the concerned undertakings and were effective in attaining their intended objective; they drew primarily from in-depth interviews with the case teams, the decision addressees and market participants. Broadcom, which started as the sole Art. 8 (interim measures) case decided to date under Regulation 1/2003, and where the remedy obligations are still ongoing, was the only case on which we could not reach a firm conclusion.

Encouraged by the rigorous case selection and the good coverage of the sample of selected cases (in addition to most of the Art. 7 cases and one in seven of the Art. 9 cases), in our study we also attempted to defy the idiosyncratic nature of antitrust cases and find more general patterns. Overall, while three quarters of the retrospectively evaluated remedies were fully implemented, less than a half of them was fully effective, suggesting that remedy design has not always been well-suited to the remedy’s objective. Remedies that were imposed with an Art. 7 decision show more numerous and more severe issues of implementation than remedies that were made binding with an Art. 9 decision. Purely behavioural remedies were less effective than structural remedies or behavioural remedies with structural elements. The remedy practice of the Commission appears to have improved over time, since issues of implementation and effectiveness are concentrated in the earlier cases.

Key recommendations of the Study

While many lessons were learned from our research, a number of them point to the imperfect functioning of Art. 7 of Regulation 1/2003. This imperfection has multiple reasons. They include: the hybrid nature of the instrument (at the same time establishing the infringement and imposing the remedies); a lack of a requirement of market testing; the statutory subordination of structural to behavioural remedies; and the legal constraints on the appointment of a monitoring trustee in the wake of the Microsoft I judgment. To overcome these limits, our study recommends that, irrespective of remedy type, remedy choice be left to the application of the principles of effectiveness and proportionality in the individual case (in line with Art. 10 of the ECN+ Directive). The Study also suggests that, in order to allow for a dedicated effort on remedy design and increase transparency, the infringement decision could in particularly complex cases be separated from the remedies decision. Finally, remedy design under Art. 7 could benefit from the type of market testing already required by Art. 27(4) for remedies under Art. 9, as well as from the appointment of independent advisors.

**

Note: The authors are among the coauthors of the study that is presented in this post. The study will be presented and discussed in an online seminar organised by DG COMP on 27 March 2025 at 12:00. The views set out in the post and the study are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect the views of their employers or the official opinion of the European Commission.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Competition Law Blog, please subscribe here.