Digital platforms behave as quasi-governments replacing regulators in their public duties of decision-making and rule-setting. To address this shift, legislators in different jurisdictions are adopting digital regulations across various fields, notably to curb digital market power or content moderation.

The striking difference between these rules and those set out in the past lies in the reversal of the burden of production. Detached from the burden of persuasion, the burden of production points to the undertaking with the responsibility of producing evidence at the start of an iterative process. The concept is unconcerned with how persuasive an argument or a piece of evidence might be before the regulator’s eyes. Rather, the notion operates against the party wishing to alter a legal conclusion and places the burden on that party, irrespective of the concerned evidence.

In this post, I explore the concept of the burden of production as a means to pressure platform power out of its private cast. By doing that, I put to the test its capacity to act as a silver bullet to counteract information asymmetries and limited observability. A fully-fledged discussion of my findings may be found in my recent working paper, available on SSRN.

The burden of production in different regulatory regimes

A fundamental shift illustrates the current digital landscape. Public and private spheres have become conflated, both at the collective and the individual level. Collectively, this means that platform private power has been left unscathed from regulatory (and public) intervention until recently. The rationale underlying the disintegration of liability hints at the idea that economic equilibrium and market reality steer digital platforms towards failure or success. Individually, users crown and depose market leaders via their interactions with digital platforms. The legitimacy of these platforms derives from a ‘private’ source of accountability. Users may desert a platform as a reaction to its transgression of mainstream values. In fact, the exodus from X to Bluesky in the millions demonstrates that this might be the case.

However, digital spaces are not completely private in nature. They bear the capacity of appropriating market outcomes to their liking, as stemming from the misallocation of liability across the web. They do so by substituting public regulatory powers within their digital ecosystems with their rule-making and standard-setting capacity. The consequences of those decisions touch upon economics in framing competition in an oligopolistic fashion as much as they relate to the interference and interpretation of fundamental rights, notably in relation to freedom of expression and information or the right to the protection of personal data.

Deliberately conflating public and private powers must trigger legal consequences for those abetting the confusion. As they did with utilities-based regulation, policymakers are progressively designing self-regulation-inspired instruments to capture private platform power. By borrowing from the rationale underlying the precautionary principle, regulators are reversing ‘walled-off’ competitive dynamics towards the public sphere.

Capturing digital platform power is not performed as an exception but by default. Digital platforms must explain before they have the opportunity to excuse themselves from liability. The reversal of the burden of proof is not the chosen means to translate the logic into reality. This mechanism entails resource-intensiveness and an initial configuration of forces in a litigation-driven scenario.

By contrast, most regulators have introduced their legal instruments by relying on the burden of production. According to US precedent, the burden of production points to the undertaking with the responsibility of producing evidence at the start of an iterative process. The burden operates against the party wishing to alter a legal conclusion. In that particular context, the burden of production and the burden of persuasion are set apart as two completely different notions playing different roles in iterative processes.

Burdens of production act as sediments to the parties’ burdens of persuasion. It is quite different to persuade someone based on evidence as opposed to the task of producing that same evidence. Those are two distinct duties which may be allocated differently to the parties. The burden of production indicates the party required to submit information or evidence about the case at hand to present a particular legal conclusion. Stemming from the need to allocate burdens according to issues based on costs for the parties, fairness and pragmatism, the burden of production is met when a party has satisfied the underlying purpose of the requirement. For instance, burdens of production are particularly relevant in the context of litigation because they indicate whether there is a reasonable disagreement between the parties about the subject matter. This disagreement will then be carried to be one of the main points of contention over which the burden of persuasion will revolve in the proceedings before the court.

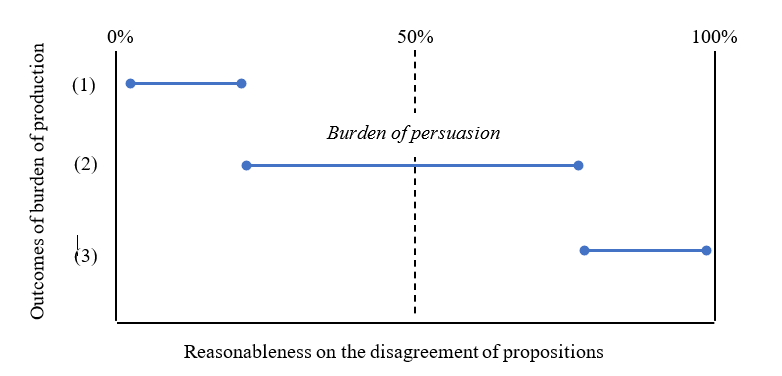

If one translates the scenario to the regulatory framework, the burden of production is instrumental to enforcement. The regulator must prioritise the instances where it must exercise its punitive and non-punitive tools to steer the target’s conduct in the regulation’s direction. Thus, the burden of production pre-determines that exercise: if the target demonstrates there is no reasonable discussion to be held with the regulator because compliance is self-evident and does not trigger further controversy, there is no point in opening a further investigation on that conduct. The burden of production acts, in these instances, as a means of screening cases, just as the figure below demonstrates:

The burden of production, which may take the form of the disclosure or the sharing of information by the regulated entity pre-determines the burden of persuasion to the extent that the less reasonable arguments presented by the regulated entities (Scenario 1) will not serve as the basis to access any kind of dialogue or contention with the regulator. Reasonableness over the parties’ disagreement is low and, as such, the target does not meet the burden of production. That automatically means that the legal consequence remains uncontested on the undertaking’s side.

In those scenarios where the disagreement between the parties is highly reasonable (Scenario 3), no further discussion with the regulator is warranted, either. The regulator’s expenditure in these types of cases would be inefficient since blatant infringements with the law are self-evident. However, the middle ground cases where the party manages to overcome the standard of scenario 1 without reaching scenario 3 (in fact, scenario 2) constitutes the remit of uncertainty surrounding the legal consequences of the case. Iterations must prevail between the parties so that the regulator and the courts may decide what legal consequences are most adequate. The parties will simply compete to make their points in line with the standard of proof set out in the law because the burden of production has been overcome, and the reasonable disagreement between the parties may fall to one side or the other.

In the context of digital regulation addressing market power, the burden of production stays with the regulatory targets throughout their interactions with the enforcer. The EU’s Digital Markets Act (DMA), the UK’s Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act (DMCC) and Japan’s Smartphone Act capture digital market power head-on by introducing hybrid enforcement systems where the need for disclosing information does not shift back and forth. An informational imbalance prevails between a digital platform’s grip over its ecosystem and rules vis-à-vis the regulator. Therefore, the regulation’s addressees must demonstrate how they comply with the regulations’ provisions by engaging with them on the merits, in two fundamental ways. First, they unveil the information which may previously have fallen beneath the regulator’s line of action. Second, they impose an enhanced obligation upon the targets to reverse the factual presumption that they do not comply with the legal requirements of the regulations.

Before the disclosure of information, the regulator decides whether those statements are entirely credible or whether it should pursue any further enforcement action. The burden of production does not fall back to the regulator because those declarations do not produce any legal effects on it. In fact, this is precisely the point where burdens of production in the context of digital regulation resemble most of those of US litigation. Burdens of production do not operate as burdens of proof shifting between the parties. Instead, they pre-determine the configuration of the parties’ iterations. In turn, the regulator picks its battles when its targeted intervention may bring the most impact to meeting the broader objectives of the regulation, especially in those cases where undertakings overcome the burden of production and enforcement must be nailed down via the burden of persuasion.

Consequences: information asymmetries and limited observability

Introducing the burden of production as a means to disintermediate information asymmetries between private regulatory powers and public regulators may, in fact, generate synergies to overcome the black-box rationale. In the absence of regulation, self-regulated entities tend to argue against any type of interference because they have more knowledge and better enforcement mechanisms than public authorities to face them. De-regulation is of the essence to ensure the most beneficial market outcomes, they argue. If left unfettered and unattended, information asymmetries arise as the situation where those private parties hold more information than the public regulator generates. Information asymmetries drive the misallocation of resources as well as transactional risks against regulators, the whole argument goes.

The burden of production impinges on this assumption and mandates transparency with the regulator regarding the information and enforcement these platforms perform across markets. By doing that, it creates informational and adaptability advantages. On one side, the regulator is preliminarily provided with sufficient information to capture the real nature of these targets’ dynamics by generating these informational advantages. On the other, adaptability advantages enable the regulator and the target to exchange their views on compliance without the direct and automatic application of a command-and-control regulatory structure. Instead, tit-for-tat iterations take place as an ongoing process where regulators and addressees engage in an experimental learning process adapted to strategic uncertainty, bearing in mind the dynamic nature of information asymmetries.

Notwithstanding, for information disclosures to be effective, much more is needed than simply imposing the legal requirement via regulation. From a managerial perspective, the undertakings must place the responsibility for disclosing information with those who possess the most information about risks and their potential control methods. For it to be feasible, it must be, therefore, less costly and more effective to comply with the mandatory disclosure requirements than to be subject to the imposition of regulatory standards or sanctions. In short, the exchange of information must report more benefits than the costs of not doing so. It is not particularly clear that this might be the case in the face of the different types of regulation capturing digital market power. The table below shows the regulators’ potential reactions to their lack of compliance with the mandated disclosure requirements:

| Digital Markets Act | Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act | Smartphone Act | |

| Punitive responses | – | Penalties for failure to comply with investigative requirements (§87(1)(a)). | Fines (Article 53). |

| Non-punitive responses | Requests of information (Article 21); Power to carry out interviews and take statements (Article 22); and Powers to conduct inspections (Article 23). | Power to require information (§69); Power of access (§71); Power to interview (§72); Power to enter business premises with and without a warrant (§74 and 75). |

In this context, both the UK’s and Japanese approaches to addressing the force of the burden of production are much more prone to aligning the undertaking’s incentives to submit complete information to their regulators. The DMCC and the Smartphone Act establish the possibility of the enforcer sanctioning the target’s unwillingness to meet the burden of production without the need to demonstrate any other substantive violation of the regulation. On the contrary, the DMA is not sufficiently equipped to address this risk as a standalone infringement with punitive mechanisms to incentivise undertakings to engage in full disclosure of their activities by providing the most accurate and appropriate depiction of their business models and functioning.

The burden of production is not a silver bullet mechanism ending with all enforcement problems relating to the original information asymmetries justifying the adoption of the regulation. Since there are a multitude of information asymmetries, there are, in turn, a multitude of enforcement challenges that need addressing. Narrowing information asymmetries is not an end in itself. It is a means to an end. This means increasing the observability of a target’s conduct in a particular context. However, the burden of production may not always deliver positive outcomes. More information does not necessarily mean increased observability will derive from it. In this same vein, transparency does not necessarily entail scrutiny by a specific forum. This is nothing especially new for regulators: targets of the regulation will be prone to insulating certain tenets of the regulation from transparency, which impacts most of their functioning.

Key takeaways

Disintermediating private regulatory power is no small feat to achieve. Digital regulation addressing market power in different jurisdictions proposes a refurbished version in the allocation of burdens to tackle such a challenge. Instead of the customary burdens of proof being imposed on targets, legislators have orchestrated a different artefact: the reversal of the burden of production against the addressees of these regulations. The difference is quickly apparent. Burdens of production do not seek to come to a conclusion in terms of the dialectical exchange with the regulator, but to set the terms of the discussion by asking whether the parties must hold a dialogue to persuade the other party.

The paper demonstrates, by taking stock of three of the main digital regulations proposed at the global stage (the DMA, the Japanese Smartphone Act and the DMCC), that such a burden of production does not necessarily entail that asymmetries of information will vanish from the regulatory perspective. Not only that, but the observability of conduct may still be at large even if the regulator tries to narrow asymmetric information dynamics. In turn, the burden of production does not challenge nor promote a regulation’s capacity to make platforms to account. It stands as a neutral mechanism which may provoke reactiveness or passivity on the target’s side. Boiling down a regulation’s effectiveness to such an aspect is not particularly promising nor aligned with the incentives of targets to iterate and substantially engage in a triangular and dialectical exchange with public regulators.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Competition Law Blog, please subscribe here.