Five years ago, the EU adopted the Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) Regulation as a key trade measure to address an increasingly complex geopolitical stage. Since it became applicable, in 2020, the number of FDI regimes in place in Europe has almost doubled (from 14 to 24), leading to an aggregate screening of over 4,000 transactions by the European Commission and the EU Member States authorities.

The geopolitical stage has not been particularly favourable to global trade and investments in recent years, and the EU’s adoption of investment screening mechanisms (such as the FDI Regulation and the Foreign Subsidies Regulation) might have played a role in this downward investment trend.

Are investors’ concerns justified, though? Our review of the data available in key jurisdictions shows that FDI rules have led to red tape, investor concerns and related regulatory costs on investors. However, a very limited number of deals are subject to in-depth reviews, commitments and prohibitions. For the vast majority of transactions subject to FDI proceedings, the greatest challenge for investors remains the handling and coordination of proceedings, minimising document and information disclosures, and obtaining timely approvals.

In this review and outlook of the EU’s FDI regime, we take stock of the first five years of the EU FDI Regulation, and we give tips to clients as to how to approach and handle FDI proceedings in the future.

Brief recap on the EU FDI Regulation

The EU’s FDI Regulation was adopted in order to identify and address risks that foreign investments could pose for security or public order beyond the EU Member State where the investment is made.

Before the FDI Regulation was adopted, there was no comprehensive framework at EU level for the screening of foreign direct investments on the grounds of security or public order. At national level, some EU Member States had screening procedures that allowed them to review large foreign investments from third countries, but these were not a significant majority in the EU. In contrast, major trading partners of the EU, such as the U.S., had already established similar frameworks, such as the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRRMA) 2018.

Today, the vast majority of the EU Member States have put in place an FDI screening mechanism. FDI proceedings play their role in ensuring that specific transactions will not affect the public interest, as defined by national authorities. However, the emergence of this patchwork of national FDI authorities and procedures might have come at a cost…

A chilling effect on (certain) foreign investments

The FDI Regulation introduces significant challenges for foreign trade and investments. It inspired national legislators and introduced a framework for the emergence of numerous FDI rules in the EU; as of October 2024, 24 EU Member States had an FDI screening mechanism, with the remaining three (Croatia, Cyprus, and Greece) having made significant progress towards implementing them. Notwithstanding this, the FDI Regulation failed to introduce common substantive rules and criteria to structure these mechanisms, leading to fragmentation.

It is difficult to predict the specific impact of the EU’s FDI regimes at a macro-economic level, especially in the context of generally decreasing net FDI flows. A number of data points do show that investors exerted caution regarding FDI rules since 2020, when the FDI Regulation became applicable. For example, in 2020, foreign investors made approx. 1,800 requests to EU Member State authorities for authorisation of their investments, of which 80% were found to be inapplicable (e.g., the request had been made out of an abundance of caution, but actually did not fall under the respective local FDI rules).[1] By 2023, 44% of FDI requests in the EU were found to be inapplicable, still a significant number that reflects investors general risk-averse approach and wariness of FDI regimes.[2]

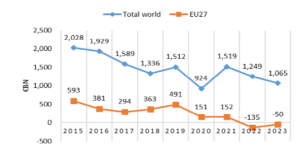

Official data also shows that foreign direct investments into the EU have taken a downwards turn or have offered a negative net balance since 2021.

World and EU inward net FDI flows

Source: OECD data, cited in European Commission Report, Fourth Annual Report on the screening of foreign direct investments into the Union, 17 October 2024

In 2022 and 2023, national FDI regimes captured investments originating predominantly from the U.S. and the UK, both in terms of acquisitions and greenfield operations. A much lower rate of deals was also captured from foreign investors in Switzerland, China and Hong Kong, Singapore and the United Arab Emirates.[3]

The data may be considered to reflect a slight deterrent effect of the FDI Regulation on foreign deals and investors, particularly those originating from the Middle East, Asia and Africa. The number of investors originating from these regions has been traditionally small, but 2017 data showed a smaller ratio between U.S.-UK-Canada transactions and transactions originating in Middle East, Asia, and Africa (between 2:1 and 4:1)[4] compared to the ratio of 8:1 we saw in 2023. 2017 data also reflected an upward trend in the number of deals originating from the Middle East, Asia and Africa, which has since been interrupted and reverted.

Are concerns of third-country investors justified?

Investors commonly raise concerns regarding the emergence of FDI-like regulations, and their likely impact on global transactions. However, are the concerns in the EU regarding the FDI Regulation warranted?

An analysis of the EU-wide data available reveals that, from the thousands of transactions subject to FDI screening in the EU since 2020, only 1-2% have been prohibited and less than 5% were aborted by the parties. The vast majority of deals notified for FDI authorisation are authorised unconditionally, with approx. 15% of the deals being subject to a condition, remedy or commitment of some type.[5]

In reviewing these data, one should take into account the fact that some FDI regimes in the EU apply to intra-EU deals (e.g., Spain, until 31 December 2024, Denmark, France), or even national transactions (e.g., the Netherlands, Norway). Oddly enough, it is some of these pure European deals that have raised most concerns in some territories. For example, in Spain, the two most renown investment prohibitions/withdrawals since the regime came into force in 2020 concerned acquisitions from other EU investors: Vivendi (notified acquisition of up to 29.9% of PRISA, notified in 2021, then withdrawn) and Ganz-Mavag Europe (notified acquisition of Talgo, notified and prohibited in 2024).

In France, several high-profile deals have been blocked under the FDI regulation. In 2020, the French government prevented the acquisition of night vision company Photonis by US-based Teledyne, despite negotiations that included conditions such as a minority stake for Bpifrance and veto rights over European operations. In 2021, the Canadian company Couche-Tard abandoned its takeover bid for Carrefour in the face of opposition from the French government. More recently, in 2023, Flowserve’s acquisition of Canadian company Velan and its French subsidiaries was blocked due to national security risks related to France’s nuclear sector. Last month, shortly after Sanofi announced talks to sell its subsidiary Opella to the American private equity firm CD&R, the French government warned that it would consider using its investment screening and veto powers if CD&R did not maintain management and production in France. These cases reflect France’s increasingly protectionist stance on foreign investments.

Preparing and coordinating FDI proceedings in the EU

Despite the introduction of investor screening procedures, such as FDI and the concentration module of the Foreign Subsidies Regulation (FSR), the EU remains an attractive region for foreign investors. The threat of an unlikely prohibition, or of conditions or remedies being imposed on a foreign investor, is most of the times theoretical, and does not necessarily depend on the nationality or country of residence of the foreign investor. The biggest costs and risks continue to be those associated with the analysis, coordination and handling of FDI approvals.

To minimise these costs and risks, investors are encouraged to engage early on with counsel in order to confirm and prepare any necessary FDI filings, further to the analysis of relevant factors:

- Are the relevant jurisdictions triggered by the presence or assets or a formal establishment in the territory, or by the mere generation of revenue (e.g., Italy, Estonia, Lithuania, Czech Republic)?

- Do the relevant jurisdictions have an investor criterion (e.g., third-country investors, non-OECD investors), a sector-related criterion (e.g., highly specialised technologies), or both?

- Do the activities of the establishments or revenues generated in the relevant jurisdictions relate to target sectors (e.g., manufacturing, supply), or to mere support/overhead activities (e.g., marketing, sales)?

- Does the investor have any precedent, or is it willing or in need of setting any precedent, regarding the filing for FDI approval in particular jurisdictions?

- What are the sanctions, penalties or other consequences resulting from a failure to make an FDI filing for a transaction (e.g., nullity of the contract)?

- Are formal or informal consultations available for investors to resolve easy cases and questions in an expedited manner (e.g., Spain, Netherlands, Italy)?

Depending on the activities of the companies involved in a transaction, and the possible jurisdictions concerned, foreign investors can generally avoid the need to make a request for FDI authorisation. Informal and formal consultations (where available) can lead to positive responses from authorities in periods between one week and one month. Even the most complex transactions can be handled without complications, provided authorities are informed about the absence of public interest concerns, and the positive externalities of the deal (in terms of investments and economic and social impact).

What lies ahead

Despite its short life, a new FDI Regulation was announced in June 2023. The Bill proposes changes that are deemed to reflect new geopolitical and security challenges, as well as address the gaps and shortcomings identified during the application of the FDI Regulation. In some instances, however, this harmonisation effort might come at the cost of eliminating high thresholds, informal consultations or other procedural advantages that characterised certain jurisdictions:

- The new FDI Regulation will oblige all EU Member States to have a screening mechanism in place. This will have a limited impact, as 24 EU Member States already have FDI screening procedures, and the three outstanding Member States (Greece, Croatia and Cyprus) are in the process of setting up theirs.

- The new FDI Regulation will harmonise national rules, particularly at a procedural level, to make cooperation with other Member States and the Commission more effective and efficient. It is still unclear whether this harmonisation will come at a cost, e.g., in relation to informal consultations.

- The new FDI Regulation will identify a minimum sectoral scope that all EU Member States are required to screen, while leaving Member States freedom to go beyond the minimum scope, depending on their own national security interests.

- The new FDI Regulation will extend the scope of EU screening to cover transactions within the EU, where the direct investor is ultimately owned by third-country individuals or entities.

****

[1] See European Commission, First Annual Report on the screening of foreign direct investments into the Union, 23 November 2021.

[2] See European Commission, Fourth Annual Report on the screening of foreign direct investments into the Union, 17 October 2024.

[3] See European Commission, Fourth Annual Report on the screening of foreign direct investments into the Union, 17 October 2024.

[4] See European Commission, Commission Staff Working Document on Foreign Direct Investment in the EU, 13 March 2019, especially Figure 2.8.

[5] See European Commission, First, Second, Third and Fourth Annual Reports on the screening of foreign direct investments into the Union, published between 2021 and 2024.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Competition Law Blog, please subscribe here.

I completely hope you continue to post blogs because the blog was quite valuable in many ways and was very simple to understand.