This year, we kick off our ‘main developments in competition law and policy’ series with this special treat!

Main Developments in Competition Law and Policy 2018-2024: Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Qatar, Palestine, Saudi Arabia (the KSA), Syria, United Arab Emirates (the UAE), and Yemen

1. Introduction and Background

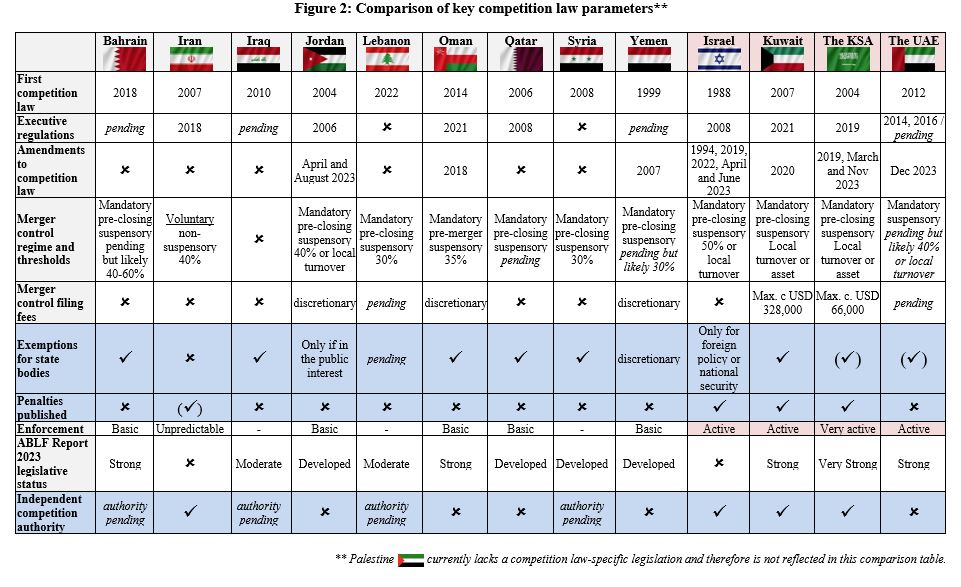

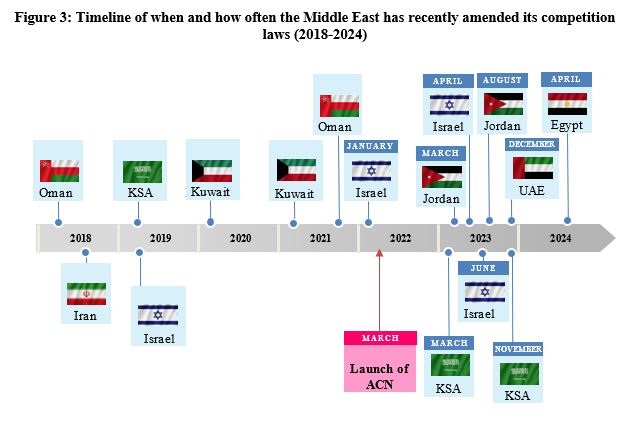

Antitrust regulation has been a relatively recent phenomenon in the Middle East compared to the well-established legal frameworks in the United States (the Sherman Act, 1890) and the European Union (EU) (Treaty of Rome, 1957).[1] The region’s national competition laws were all introduced (well) after the EU rules and many have been influenced by them: Middle Eastern countries introduced their first competition laws between 1988 and 2022, starting with Israel (1988) and ending with Lebanon (2022), highlighting a gradual regional adoption of such laws over three decades. (Tunisia was the first Arab country that adopted competition specific legislation in 1991.)

According to the latest report by the United Nations (UN) which evaluates the robustness of Arab competition legislation against international standards (“ABLF Report”), the Arab region advanced its ranking from “Moderate” in 2020 to “Developed” in 2023.[2] In particular, for the six Arab countries making up the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, the KSA, and the UAE), the average score enhanced from “Developed” to “Strong” due to legislative amendments in Kuwait, Oman, and the KSA.[3] Only two countries, Egypt and the KSA, outranked others and obtained the highest score “Very Strong” in 2023.

While the ABLF Report confirms a trend for increased competition legislation across the Middle East, its classifications do not reflect the enforcement level of competition laws.

We view the Turkish Competition Authority as active and engaged, comparable to its counterparts in the EU or US, and acknowledge its evolving approach to complex economic reasoning and theories of harm in its decisions. Meanwhile, we observe substantial divergence across the Middle East, ranging from no practical enforcement (e.g., Iraq and Syria) or only basic enforcement (e.g., Bahrain, Iran, Jordan, Oman, Qatar, Yemen) to an increasingly sophisticated and rigorous approach (especially the KSA).

This article covers the following selected 14 countries: Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Qatar, Palestine, the KSA, Syria, the UAE, and Yemen (together the “Middle East” or the “region”). References to the “Arab region” or “Arab countries”, on the other hand, comprise the 22 Arab League member states (Algeria, Bahrain, Comoros, Djibouti, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, the KSA, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, the UAE, Yemen). For the benefit of comparison, we occasionally draw comparisons with the EU, Turkish, and Egyptian competition law frameworks to provide additional context and insights.

This article analyzes key competition law and policy advances in the Middle East, by setting out the legislative evolution and delving into recent developments (2018–2024). We will (i) first discuss the jurisdictions whose competition regime we view as still in the early stages of development, followed by (ii) jurisdictions whose competition authorities we observe to be increasingly rigorous, and (iii) a deep dive into:

- the KSA, where enforcement has continuously strengthened since its antitrust reform in 2019; and

- the UAE, which has revamped its competition law at the end of last year, 2023.

We will conclude with a forecast for the region. In brief, considering the recent uptick in antitrust developments, coupled with continued projected economic growth, enforcement of competition rules in the Middle East will only strengthen. To the extent that this will safeguard competitive markets, this is to be welcomed. Given the KSA’s and the UAE’s priority of creating a conducive investment climate, fears of an unduly interventionist approach by antitrust regulators in the Middle East seem misplaced, at least for now. That said, the broad jurisdictional scope of the KSA’s merger control, which often triggers filing obligations even for transactions with a limited direct nexus to the KSA, remains an important consideration.

2. Jurisdictions whose competition regime is still in the early stages of development: Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Oman, Qatar, Syria, and Yemen

Consumer Protection Directorate of the Ministry of Industry, Commerce & Tourism – إدارة حماية المستهلك في وزارة الصناعة والتجارة

The Kingdom of Bahrain’s first comprehensive competition law, Law No. 31 of 2018 Concerning the Promotion and Protection of Competition, was introduced in 2018.[4] In January 2019, Royal Decree No. 8 of 2019 stipulated that the Consumer Protection Directorate of the Ministry of Industry, Commerce & Tourism is responsible for enforcing the law pending the appointment of the Competition Authority.

Competition law

Key aspects of Bahrain’s competition law include the prohibition of anti-competitive arrangements, such as price-fixing (Article 3) and collusive bidding (Article 3). The law addresses abuse of dominance, defining a “dominant position” as the ability to prevent effective competition in the market, which applies to entities with over 40% market share or groups with over 60% market share (Article 8). While the law prohibits the abuse of such dominance, it does not bar entities from holding a dominant position. Companies in a dominant position are prohibited from engaging in practices that unfairly limit competition, including but not limited to imposing unfair trading conditions or engaging in predatory pricing.

The competition law provides certain exemptions including for facilities and projects owned or managed by the state (Article 2(b)) and on grounds of public policy (Article 15).

Fines for failure to comply with any aspect of the competition law are up to 10% of the party’s total annual turnover in Bahrain for the period in which the breach occurred (to a maximum of three years) (Article 49). The competition law states that further guidance should be provided by the authority on the calculation of fines (possibly in the implementing regulations).[5] No fines (for antitrust or merger control related violations) have been published to date.

Merger control

The competition law and Regulation No. 72 of 2019 (Regulatory Controls on Economic Concentrations) provide a mandatory and suspensory pre-closing merger control regime. However, Bahrain has not yet adopted the requisite implementing regulations and therefore there are currently no notification thresholds.[6] The latest ABLF Report nonetheless, and somewhat surprisingly, upgraded the status of Bahrain’s competition legislation from “Developed” in 2020 to “Strong” in 2023, due to minor advancements across the examined components (including in its competition enforcement practices and merger regulatory regime).[7]

The competition law generally prohibits an economic concentration that results in the significant reduction of competition in the market. Absent any concrete notification thresholds but given that the current Regulatory Controls on Economic Concentrations are already applicable, merging parties may consider notifying before closing, any transaction that is likely to significantly impede competition in Bahrain to avoid fines post-closing.

Iran – unpredictable enforcement[8]

Competition Council – شورا و مرکز ملی رقابت

Iran’s Competition Council was created to achieve the objectives of “promoting competition and prohibiting monopolies” and has far-reaching powers, e.g., there is no time limitation on when the authority may commence a review.[9] The Council holds sole authority to investigate and make decisions on anti-competition procedures, initiating probes as necessary (Article 62). The Council is said to operate independently from the government, with its 15 members—experts in law, economy, trade, and finance—appointed by Iran’s President and removable only upon loss of legal capacity. The additionally created National Competitive Council is an independent government institution that manages the Council’s professional, executive, and other affairs.[10]

Competition law

While there is only limited transparency and little access to the relevant law, key aspects of Iran’s 2007 Law on Implementation of General Policies of Principles of Article 44 of the Constitution (the “Privatization Act”) include the prohibition of anti-competitive practices such as exclusive dealing, price discrimination and dumping (Articles 47 and 48).[11] The Competition Council can punish infringements of the competition law with fines and other remedies (pursuant to Article 61). The competition law applies broadly across economic sectors, excluding those tradespeople and businesses engaged in small-scale retail and regulated under the Guild Regime Act (Article 50). Unlike most competition laws in the Middle East, the Privatization Act does not exclude governmental entities from its scope and it also does not provide for maximum fines. [12]

Merger control

Iran is the only country in the Middle East with a voluntary, non-suspensory merger control regime (since 2007), i.e., there is no obligation to notify a transaction before or after its completion. As a result, there is no fine for failure to file.

The Executive Instructions of Articles 47, 48, and 49 of the Privatization Act were ratified in 2018 but still leave various gaps and uncertainties particularly with respect to acquisitions. While any merger that leads to extreme market concentration (i.e., above 40% market shares and the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index is more than 4000) is explicitly prohibited, also acquisitions that “disturb” market competition are prohibited.[13] No criteria are given for the latter.

Indeed, with one exception, there is no publicly available information about the authority’s activities. The one merger control decision that is available concerned the combination of two major Iranian online discount companies, Takhfifan and Netbarg. In December 2022, the authority ordered the transaction to be unwound three years after its completion. This decision was prompted by a competitor complaint. The decision did not set out any reasoning other than that it created an unacceptable concentration in the market. It is not clear from public sources whether the parties appealed to the Competition Board of Appeal.[14]

Accordingly, despite the lack of clear rules, merging parties may wish to engage (formally or informally) with the Iranian Competition Council if they contemplate a significant acquisition in Iran which may trigger customer or competitor complaints to the authority.

Council for Competition and Antimonopoly Affairs – مجلس شؤون المنافسة ومنع الاحتكار

Iraq’s Competition and Prevention of Monopolies Law (14 of 2010) “aims to regulate the competition and prevent the harmful monopolistic practices in the society by investors, producers, marketers or others in all economic activities” (Article 2).[15]

To date, Iraq has not yet established its competition authority (which is to be named Council for Competition and Antimonopoly Affairs) nor any implementing regulations. As a result, Iraq’s competition law remains unenforced, with its stipulated penalties, including imprisonment of one to three years or fines of c. USD 2,300, currently not being applied.[16] There is no indication as to when the dedicated authority might be established.

Competition law

Iraq prohibits any transaction or agreement that would create or increase a market share of 50% or more (Article 9). The law also encompasses provisions against anti-competitive practices such as price-fixing and collusion, aimed at ensuring market fairness. A market share of 50% or greater constitutes a dominant position. The law excludes governmental entities from its scope.

Merger control

However, unlike Iran which provides for a voluntary regime, Iraq has not introduced any merger notification regime at all. The latest ABLF Report downgraded the status of Iraq’s competition legislation from “Developed” in 2020 to “Moderate” in 2023.[17]

Directorate of Competition of the Ministry of Industry, Trade and Supply – مديرية المنافسة في وزارة الصناعة والتجارة والتموين

Jordan’s Competition Law No. 33 of 2004 replaced Competition Temporary Law No. 49 (2002) in September 2004 and strives to “protect and promote competition in Jordan”.[18] The Economic Concentration Instructions No. 2 of 2006 followed thereafter.[19]

In July 2022, the Jordanian government proposed amendments to the competition law including additions to the list of anti-competitive practices, increased penalties, and clarifications on the concept of economic concentration, abuse of dominance, and the powers of the directorate. In March 2023, the parliament approved the proposal and on May 16, 2023, the Amended Competition Law No. 12 of 2023 came into effect.[20] On August 3, 2023, the Council of Ministers Decision No. 43223 supplemented the amended law to introduce merger control thresholds. The latest ABLF Report upgraded the status of Jordan’s competition legislation from “Moderate” in 2020 to “Developed” in 2023.[21]

The Directorate of Competition of the Ministry of Industry, Trade and Supply is in charge of enforcing the competition law, but does not have sanctioning or remedial powers and must refer cases to the public prosecutor for the imposition of penalties. Among the key changes to Jordan’s competition law are the following:

- The Competition Affairs Committee has been created as the advisory body of the Directorate.

- However, the Minister of Industry, Trade and Supply has the power to (i) order the parties to undertake necessary steps to restore the pre-transaction structure and to (ii) annul the directorate’s merger control approval which may be subject to appeal before the administrative court.

- Also, Jordan’s Minister of Industry, Trade and Supply may issue exemptions to competition rules “if in the public interest”.

- Although the latest amendments provide more guidance, lack of transparency and independence in competition law enforcement remain. Indeed, former Minister of State for Economic Affairs, Yusuf Mansur, heavily criticized the latest amendments for being “new, deformed and paralyzed”, arguing that enforcement should not lie in the hands of a government ministry but in the Directorate.[22]

Competition law

Article 3 of the amended law provides for the competition law’s application to “all economic activities conducted inside Jordan or outside it if they impact the internal market”.[23]

The new law establishes key definitions, including market and dominant position, and broadens the scope of “economic activity” to encompass sectors such as IT and professional services (Article 2). It prohibits anti-competitive practices, including price fixing, market division, and restrictions on production and distribution (Article 5(a)), while granting exemptions under Article 5(b) for agreements with limited market impact, provided they do not involve price fixing or market division.

The competition law further prohibits abuse of dominance, including price fixing, imposing market barriers, suspending purchases, manipulating supply to create shortages or surpluses, and selling below cost. (Article 6(a)). The law now clarifies the concept of “dominant position” by listing specific factors to assess market dominance, including market share, financial capacity, access to supply chains, relationships with affiliates, and barriers to competitor entry. It introduces a 40% market share threshold for dominance, considering an enterprise dominant unless it proves exposure to effective competition. Unlike the old law, which only referenced this threshold for economic concentration approval, the amended law explicitly uses it to define dominant market status.[24]

The legal maximum fines have doubled to c. USD 141,000. As fines have to be issued by the court, they are a matter of public record. Publicly available sources do not show that fines have previously been imposed and from experience, the Directorate has not applied to the court for fines for failure to notify or gun-jumping.[25]

Merger control

Jordan has a mandatory and suspensory pre-closing merger control regime. Among the key changes to Jordan’s merger control regime are the following:

- Merger control clearance is required for transactions where the parties’ combined market share is above 40% or where the parties’ combined local revenue exceed c. USD 9.8 million, or where at least one party has local revenue of c. USD 2.8 million.[26] These turnover thresholds are remarkably low in comparison to those in other Middle Eastern countries, but similar to those in Kuwait.

- The party(ies) making the notification must pay the fees incurred by the directorate to publish the transaction details in two daily newspapers.

- The amended competition law empowered the Minister of Industry, Trade and Supply to issue instructions on “all matters related to economic concentration” in the Official Gazette, based on recommendations from the Committee (Article 10(f)).[27] These instructions have not yet been issued.

National Competition Authority – الهيئــة الوطنية للمنافسة

Lebanon’s first comprehensive competition legislation, Competition Law No. 281 of 2022, was issued in March 2022. [28] The latest ABLF Report upgraded the status of Lebanon’s competition legislation from “Weak” in 2020 to “Moderate” in 2023.[29] The National Competition Authority has exclusive competence in competition matters and must approve sector concentration operations, requiring cooperation and technical input from sector regulators before final approvals (Article 6).

However, since the National Competition Authority responsible for enforcing the competition law has not yet been created, Lebanon’s competition regime is not yet in force. It is unclear when this might change.[30]

Competition law

Chapter 2 of the new Lebanese competition law prohibits anti-competitive practices and agreements, including collusion on prices, restricting goods flow, market sharing, production limits, bid collusion, and blocking market entry (Article 7). Dominant market positions are defined as those with a minimum market share of 35% (individual) or 45–55% (groups), and abuses like price manipulation, discriminatory contracts, and exclusionary practices are prohibited (Article 9). Certain license conditions and restrictive vertical agreements, which harm competition, are also barred (Articles 8 and 11). Exceptions exist for agreements that benefit economic development, improve production, support small enterprises, or boost competitiveness in international markets (Article 7).

Merger control

Lebanon established a mandatory and suspensory pre-closing merger control regime. Merger control clearance is required for transactions where the parties’ combined (or individual) market share is above 30% of the relevant market in the last three fiscal years (Article 14). Article 22 imposes sanctions for unreported or prematurely executed concentration operations. Failure to report requires filing or reverting to pre-concentration status, with fines up to 5% of turnover and operation suspension. Completing a concentration before approval similarly incurs fines and suspension. Omitted or false information can lead to fines, approval withdrawal, and re-reporting.

Competition Protection and Monopoly Prevention Centre – مركز حماية المنافسة ومنع الاحتكار

Oman’s first competition specific legislation, Royal Decree No. 67 of 2014 Promulgating Competition Protection and Monopoly Prevention Law, was enacted in 2014.[31] Originally, the Public Authority for Consumer Protection was in charge of enforcing the competition law. This changed in 2018 with the entry into force of Royal Decree No. 2 of 2018 introducing the Competition and Monopolies Prevention Centre Law. This law (i) created a dedicated competition regulator, the Competition Protection and Monopoly Prevention Centre (under the auspices of the Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Investment Promotion), and (ii) changed the merger control regime.[32]

In January 2021, Ministerial Decision 18/2021 issued the executive regulations for Oman’s competition law to offer more clarity to the existing legal framework.[33] The latest ABLF Report upgraded the status of Oman’s competition legislation from “Developed” in 2020 to “Strong” in 2023.[34]

Competition law

Oman’s competition law prohibits practices that limit competition, including price-fixing, limiting production, market sharing, and bid-rigging (Article 9) and prohibits abusive dominance, such as selling below cost to eliminate competitors, and refusing supply access (Article 10). Dominance is defined as having over 35% market share (Article 4).

Penalties for violations include fines between 5% and 10% of the annual turnover from the last fiscal year and imprisonment from three months to three years, depending on the infraction’s severity (Articles 19 and 20). Fines primarily target anti-competitive practices; penalties such as imprisonment and 5%–10% of annual turnover are imposed for violations like price-fixing and abuse of dominance (Article 19). For economic concentration (merger control), non-compliance with reporting or accurate information requirements incurs capped administrative fines of up to c. USD 260,000, rather than turnover-based penalties, reflecting a procedural focus (Article 20).

Oman competition law exempts activities (i) relevant to the public facilities fully owned or controlled by the state or (ii) relating to research and development conducted by any public or private bodies (Article 4). It also permits temporary exemptions from competition rules for agreements or practices that reduce initial costs, benefit consumers, or support restructuring, quality improvements, technical progress, Omani SMEs, or environmental initiatives (Article 5).

Merger control

Oman has a mandatory and suspensory pre-merger notification system, requiring clearance for transactions with a post-merger market share of at least 35% in Oman (Article 11).[35] The Ministry has 90 days to approve, conditionally approve, or reject applications, with automatic approval if no decision is made within this period (Article 12).

As is the case for the UAE, Kuwait, Bahrain, and Qatar, there is no publicly available information in Oman about the track record of its competition law enforcement. It is thus not clear how Oman’s competition authority operates in practice and whether it has already imposed fines or remedies, and/or blocked any deals.[36]

However, it appears Oman is trying to become more active in its competition law enforcement. For instance, the Oman News Agency reported in October 2023 that the competition authority organized a workshop to “exchange knowledge, experience and create[ing] a greater awareness of the role and importance of the competition”. More than 100 competition law experts from different governments and private stakeholders attended. The chairman of the board of directors of the competition authority stated that the objective is “to recognize local and global developments and applying the best international practices in competition”.[37]

Competition Protection and Antimonopoly Committee – لجنة حماية المنافسة ومنع الممارسات الاحتكارية

Qatar’s Law No. 19 of 2006 Concerning Protection of Competition and Prevention of Monopolistic Practices[38] was issued in 2006 and its Executive Regulations No. 61 of 2008[39] followed thereafter. The latest ABLF Report showed no change in the “Developed” status of Qatar’s competition legislation in 2023, reflecting the absence of legislative developments since 2008.[40]

The Competition Protection and Antimonopoly Committee is the national competition enforcement authority and its vision is to “work towards free competition based on advanced rules far from monopoly practices”.[41] The committee is affiliated with the Minister of Economy and Commerce and includes economic, financial and legal experts.

Competition law

Qatar’s competition law prohibits anti-competitive practices, including price manipulation, market division, limiting production, and bid-rigging (Article 3), while dominant firms are barred from practices that restrict competition, such as refusing supply or unfairly setting conditions (Article 4). To date, the authority has not offered explicit guidance on the definition of a dominant market position (see further below).

The Qatari competition law applies to all entities (including activities that take place outside of Qatar that have an effect on competition in the Qatari market) except Qatari state owned bodies/entities or entities subject to state direction or supervision (Article 6). Parties can also seek a special resolution from the Minister of Economy and Commerce to exclude a transaction from the competition law and executive regulations, on grounds of consumer welfare.

A violation of the Qatari competition law can be penalized by a fine of no less than c. USD 27,000 and no more than c. USD 1.37 million. In all cases, the court shall confiscate all profits resulting from activities in violation of the provisions of the competition law (Article 17).[42] The court could issue fines and they would therefore be a matter of public record. We are unaware of any fines for failure to notify or gun-jumping being applied for by the committee to the court.[43]

Merger control

Qatar has a mandatory and suspensory pre-closing notification regime. However, as of today, the competition law, the executive regulations, and committee decisions do not identify any exact criteria for triggering a notification obligation:

- The law and regulations do not explicitly address a change of control as a trigger for a merger filing. Although the law suggests merger control might apply to change of control transactions, the authority may still require notification for transactions without a change of control. Specifically, it involves acquiring assets, rights, or shares, or merging entities in a way that creates a dominant market position, where one or more entities can effectively control or influence prices and the availability of goods or services, limiting competitive options for others in the market (Article 10).

- The executive regulations state that the Qatari competition authority will assess whether a transaction is notifiable based on: (1) its potential impact on competition in Qatar’s market; (2) the benefits to consumers; (3) any increase in efficiency and improvement in product and service quality; and (4) the frequency of similar transactions in the relevant market. Based on (1) above, transactions where the parties have or obtained a 40% market share could be seen as one notification threshold, given that this establishes a dominant market position as defined by another law, namely by Article 288 of the Commercial Companies Law No. 11 of 2015.[44]

- Ultimately, notification thresholds are, as a matter of practice, determined by the authority on a case-by-case basis, e., considering the potential impact of a particular transaction.

Given that the Qatari merger control regime thus far remains “largely inactive”, there is little practical guidance on how the authority will apply the law.[45] Absent guidance from the authority, parties should consider whether to approach the regulator for acquisitions that result in a dominant position in a market in (or including) Qatar, even if there is no substantive overlap. The competition law mandates that applications be processed within 90 days of submission to the committee; if not addressed within this period, the application is automatically approved (Article 10).

There have not been any recent changes to the legislation or implementing regulations and significant uncertainty remains (especially as regards the jurisdictional merger control thresholds). Due to the absence of public information about the committee’s antitrust enforcement history, it is difficult to ascertain how active it is.

Palestine currently lacks a competition law-specific legislation and as such does not have a merger control regime in place:

- In May 2017, ESCWA organized a capacity-building workshop in Amman, Jordan for Palestinian officials to develop a competition framework, enhancing their capacity to implement competition policies and fostering interest in competition’s role in private sector and economic development.[46]

- There is thus no ABLF Report, except on Palestine’s Consumer Protection Law No. 21/2005, amended in 2018, which addresses consumer rights, product safety, supplier obligations, and redress mechanisms.[47]

- At a July 2020 OECD Competition Law & Policy Live Event, Mr. Jamal Abu Farha, Director General of the Competition General Directorate in Palestine, stated that “Palestine does not have a competition law at the moment”. He explained that Palestinian authorities have adopted an open market policy and signed several trade treaties with countries such as Turkey, the USA, and EU countries. Despite ongoing efforts to finalize a competition law since 2003, no independent competition enforcement body has been established given Palestine’s political challenges and limited financial resources. [48]

Syria – no enforcement

Syrian Competition Protection and Anti-Monopoly Commission – هيئة المنافسة ومنع الاحتكار

Syria’s Law No. 7 of 2008 Competition and Antitrust Law was issued in 2008 “to promote the Syrian market as a potential base for local and foreign investors”.[49] The latest ABLF Report upgraded the status of Syria’s competition legislation from “Moderate” in 2020 to “Developed” in 2023, due to advancements in its anti-dominance and monopolization laws and merger regulatory regime.[50]

Competition law

Syria’s competition law prohibits anti-competitive practices, including price-fixing, bid-rigging, market division, and limiting production or market access (Article 5). A dominant position is defined as a market situation where an entity, alone or with others, has substantial control over a market segment, enabling it to limit market access, reduce competition, or influence market conditions (Article 6). Abuse of dominance, such as selling below cost to harm competitors, discriminating in similar contracts, and imposing unfair trade terms, is also restricted (Article 6). Syria’s Competition Law specifies a 30% market share threshold for dominance solely for economic concentrations under the merger control regime and thus cannot be taken as definitive guidance for abuse of dominance cases outside this context. (Article 9).

Violations of the law may result in a fine of 1–10% of the annual total sales of goods or revenues of services (Article 23).[51] State-owned enterprises (“SOEs”) and sovereign activities are exempted from the provisions of the competition law.[52]

Merger control

Economic concentration, defined as transactions that enable an entity to control another entity’s operations, requires prior clearance if the resulting market share exceeds 30%, with approval granted if competition is not significantly harmed (Article 9).

There is limited publicly available information regarding the activities of the Syrian Competition Protection and Anti-Monopoly Commission, including due to ongoing political and humanitarian challenges.

Public Authority to Promote Competition and Prevent Monopolies and Commercial Fraud – جهاز حماية المنافسة ومنع االحتكار

Yemen’s Republic Decree Law 19/1999 on Promoting Competition and Prevention of Monopolies and Commercial Fraud aims to ensure a “free competitive trade framework so that no consumers’ interests are harmed or commercial monopolies are created”.[53] In 2007, the Ministerial Decree 128/2007 on the Regulation of Competition and Prevention of Monopolies, issued by the Ministry of Industry and Trade, created the Public Authority to Promote Competition and Prevent Monopolies and Commercial Fraud. The latest ABLF Report showed no change in the “Developed” status of Yemen’s competition legislation in 2023, reflecting the absence of legislative developments since 2007.[54]

Competition law

Yemen’s competition law prohibits anti-competitive practices, including price-fixing, market division, production restrictions, and bid-rigging (Article 7). Abuse of dominance, such as selling below cost to harm competitors, price discrimination, tying sales to other products, and withholding supplies, is also forbidden (Article 8). The law does not specify a particular market share threshold for defining economic concentration or dominance.

Yemen’s competition authority may impose fines ranging from c. USD 40 to a maximum of c. USD 400 and supplementary penalties, such as a suspension or revocation of local licenses, closure of business premises, and blacklisting for breaches of the competition law (Article 22). The authority also reserves the right to order the reversal or annulment of transactions. Beyond penalties imposed on transaction parties, the authority can hold directors, general managers, and auditors of violating entities personally liable for any damages resulting from or associated with the failure to notify the authority in a timely manner.

Exemptions can be granted by the competent authorities on a case-by-case basis (Article 4). However, these exemptions are very rare and require significant political endorsement.[55]

Merger control

In 2007, Yemen introduced its mandatory and suspensory pre-closing merger control regime. However, the decree is vague and does not provide guidelines on its implementation. For instance, there are no fixed merger control notification thresholds but instead, reference is made to vague definitions of market impact, i.e., “concentration is prohibited if it leads to restrain or weaken competition” (Article 9). Local practitioners state that the authority in practice applies a market share notification threshold of at least 30%.[56] As a result, even those transactions that do not meet the 30% perceived/practiced market share threshold can be notifiable if they potentially have a competitive impact.

There have been no significant legislative changes or efforts to address merger control in Yemen since 2007. There have not been any noteworthy transactions notified in Yemen in recent years.[57] In addition to the lack of clear standards and absence of decisions published by the authority, the effectiveness of competition law enforcement in Yemen is limited by the broader socio‑political context of political instability and armed conflict.

3. Jurisdictions whose competition authorities have become increasingly rigorous: Israel, Kuwait, the KSA, the UAE

Israel – active enforcement[58]

For an in-depth analysis of the ICA’s enforcement practices and activity, please refer to the latest developments published as part of this Kluwer Blog Series. For comparative and completeness purposes, however, we set out the following:

Israeli Competition Authority – רשות התחרות

With the entry into force of Economic Competition Law 5748 in 1988, Israel was the first country in the Middle East to implement competition specific legislation.[59] The Israeli Competition Authority (“ICA”) was established in 1994 with the passage of the Antitrust Law Amendment and the addition of Article 41 to the law.[60] The ICA is “an independent professional authority working to protect the public from harms to competition and to promote competition, for the good of the public”.[61]

The publication of the related Guidelines of the General Director of the Israel Antitrust Authority For Reporting and Evaluating Mergers followed 20 years later, in 2008.[62] Since then, the ICA has published multiple additional laws and guidelines (including, e.g., on the merger control process, the calculation methodology of financial sanctions, and the promotion of competition in the food sector, to mention but a few,[63] and most notably in 2019 and 2022).[64]

Merger control

Israel has a mandatory and suspensory pre-closing notification system. Any transaction in which one company acquires “substantial influence” over the decision-making process of another company is deemed a “merger”. This includes acquiring over 25% of rights related to appointing directors, voting, dividends, or shares. Acquiring a company’s main assets may also be seen as a merger. There are three alternative threshold tests (one being a 50% market share threshold and the other two are based on local turnover) and meeting any of them triggers a filing, provided that at least two of the merging parties have “sufficient nexus to Israel” within the meaning of the guidelines.[65] Israel’s Minister of the Economy can grant exemptions where necessary for foreign policy or national security purposes. There is no filing fee. The ICA processes transactions that evidently do not raise competitive concerns in the “bright green” expedited review track and frequently clears them within five working days. [66]

Comparative remarks

Along with the Turkish Competition Authority, we see the ICA as among the most mature and well‑established competition authorities in the Middle East. The ICA works closely with authorities in Europe and the US and is an active member of the International Competition Network.[67] Israel is among the three countries in the region (together with Turkey and Egypt) that is a member of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and its Competition Committee. On the other hand, Israel, Iran, and Turkey are the only countries in the Middle East (broadly defined) that are not members of the recently launched Arab Competition Network (“ACN”), which will be discussed in the final section.

Unlike most countries in the region (except the KSA), the ICA publishes penalty decisions on its website. [68]

Kuwait passed its first competition law in 2007 (Law No. 10 of 2007 on the Protection of Competition) and created the Competition Protection Agency under the Ministry of Commerce and Industry in 2012 to enforce it.[69] Articles 4 to 6 of the implementing regulations clarify that the agency is financially and administratively independent.[70]

In 2020, Kuwait enacted a new law, the Protection of Competition Law (Law No. 72 of 2020),[71] as well as implementing regulations under Resolution No. 14 of 2021.[72] In September 2021, the agency issued Resolution No. 26 of 2021 which specified the new pre-merger notification thresholds (based on Kuwaiti turnover/asset thresholds).[73] The latest ABLF Report classified Kuwait’s competition legislation between 2020 and 2023 as “Strong”.[74]

Competition law

Kuwait’s competition law prohibits anti-competitive agreements, including price-fixing (Articles 5-6) and abuse of dominance which however is not defined by a threshold. The new law introduced new enforcement powers to the authority (e.g., to impose fines of up to 10% of a company’s annual turnover including for obstructing an investigation) (Article 34). [75]

Certain competition law exemptions exist for transactions involving fully state-owned entities (i.e., activities of public utilities and SOEs that provide basic goods and services to the public, as established by a decision of the Council of Ministers (Article 3))sectors exempt from merger control by statute, or research and development activities in Kuwait. [76] However, clearance from sector-specific authorities may still be required.

Merger control

The new law replaced the previous merger control regime (premised on a 35% combined market share test) with a mandatory and suspensory pre-closing notification regime.

The merger control thresholds are low in comparison to those of other jurisdictions in the region but similar to those in Jordan, namely combined annual sales in Kuwait of c. USD 2.5 million and combined assets in Kuwait of c. USD 8.2 million. While the single party threshold specifies domestic turnover, Ministerial Decree 26/2021 does not state whether the combined party threshold includes worldwide turnover. In practice, the authority considers only domestic turnover for both thresholds.[77]

No market share threshold applies (but this information must be provided as part of the notification form). Given that these thresholds refer to combined values, they can be met by the acquirer only—there is no clear exemption for transactions that involve a target with no direct local nexus to Kuwait.

Failure to notify or suspend transactions under Kuwait’s merger control may lead to fines of up to 10% of annual turnover, doubled for repeat offenses. Although the CPA has not penalized merger control violations yet, recent fines—including 1% for a steel manufacturer and up to 5% for supermarkets over anti-competitive practices (see below)—show its willingness to enforce substantial penalties. Both cases involved companies with only Kuwaiti turnover, and the CPA’s decisions did not clarify if fines are based on domestic or worldwide turnover, leaving this point unresolved.[78]

The agency will calculate the merger filing fee as 0.1% of either the paid capital or the value of the assets of the parties in Kuwait, whichever is lower. This fee is capped at c. USD 328,000, making it the highest in the region, however, in practice, filings fees are likely to remain below this maximum given that they its calculation is based on paid capital or assets in Kuwait rather than revenues in Kuwait. By way of context and comparison, the maximum filing fee cap in the KSA was recently almost halved from c. USD 106,000 to c. USD 66,000.[79]

The agency was historically dormant and relatively inactive compared to other jurisdictions in the region. However, since the issuance of the new competition law four years ago, the agency has consistently increased its level of enforcement and investigative activity. The agency has started publishing announcements of its activities e.g., its merger control approvals (or conditions), fines, public outreach initiatives.[80] For instance:

- The agency has started contacting companies to inquire about transactions that were not filed.[81]

- To date, there is no announcement of a denial or rejection of any economic concentration applications.

- In November 2022, the agency imposed a fine of c. USD 806,000 on an unnamed steel distribution company (equivalent to 1% of the company’s total revenues achieved during the fiscal year 2020/2021), for the company’s failure to provide information in response to the agency’s request within the allocated 30 days.[82] The request followed from the agency’s market study evaluating increased steel prices. In January 2023, fined the same company c. USD 5.7 million (equivalent to 7% of its revenues achieved during the 2022 fiscal year) for withholding products to create scarcity and drive up prices, violating competition rules.[83]

- In November 2021, the agency announced its conditional approval of Bahraini company Kalaam Telecom’s acquisition of Kuwait-based Zajil Telecom for c. USD 54 million, subject to the agency monitoring the companies’ prices and quality of services for a period of one year post-closing.[84] The agency also obliged the companies to provide copies of their customer contracts within a month after closing, and not to engage in any refusal to deal, withholding products, or tying arrangements.

- In 2022, the Kuwaiti competition authority signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the Saudi competition authority to hold regular meetings on merger control and competition issues and to exchange information. Initial meetings have taken place, but it is unclear if a continuous information exchange mechanism for filed transactions has been established.[85]

- In March 2023, the agency issued its highest-ever fine of c. EUR 26 million against 14 supermarkets for individually abusing their dominant positions by coercing suppliers into offering them free goods.[86]

4. Deep-dive into the very active Saudi competition regime

General Authority for Competition – الهيئة العامة للمنافسة

The KSA enacted its first competition law in 2004.[87] In October 2017, Council of Ministers Resolution No. 55 renamed the “Council of Competition” to the “General Authority for Competition” (“GAC”). In September 2019, the new competition law promulgated under Royal decree No. M/75 of 29/06/1440H[88] and the corresponding implementing regulations[89] came into effect, replacing the previous law. This amendment marked a major shift in the Saudi competition law framework. Ever since, the GAC started positioning itself at the forefront of competition law enforcement in the region.

The GAC is solely responsible for overseeing and implementing the competition regime aimed at protecting and encouraging fair competition, while combating monopolistic practices that could harm lawful competition or consumer interests. Unlike most competition authorities in the Middle East (with the exception of Israel, Kuwait, and Turkey), the GAC officially operates independently from the government. Article 2(1) of the GAC regulation grants it separate legal status as well as financial and administrative autonomy. Importantly, this independence extends beyond the institution itself. The implementing regulations mandate that GAC officers adhere to strict impartiality rules and avoid conflicts of interest while performing their duties (Article 67).[90]

In 2021, a royal order appointed former royal advisor Ahmed bin Abdulkarim Al Khulaifi as the chairman of the GAC.[91] His previous roles at the Saudi Central Bank demonstrate the government’s commitment to establishing a modern competition law regime as part of its Vision 2030 program.[92]

The GAC issued two sets of merger guidelines: the first in April 2020, clarifying the calculation of the notification threshold, and the second in July 2021, providing comprehensive guidance on the merger control regime.[93] Indeed, the latest ABLF Report upgraded the status of the KSA’s competition legislation from “Developed” in 2020 to “Very Strong” in 2023. [94] Egypt and the KSA are the only two Arab countries that the ABLF Report gave its highest ranking. It seems likely that if the Turkish and Israeli competition laws were covered in the ABLF Report, they would also be in the top ranks.

In line with most competition laws in the Middle East, albeit in a more restricted and nuanced way, Saudi competition law exempts public sector corporations or companies fully owned by the state, provided they are exclusively authorized by the government to offer products and services in a specific field (Article 3).[95] The GAC may exempt certain practices if they result in improvements to quality, innovation, or consumer benefit that outweigh competitive restrictions. Exemptions are granted only when they do not eliminate competition or competitors. Exemptions are reviewed and may be extended if they continue to provide net consumer benefits without distorting competition excessively. [96]

Below is a brief overview of the KSA’s key competition law aspects:

- Prohibited Anticompetitive Practices and Agreements: Agreements between firms that undermine competition are prohibited, regardless of whether they are formal or informal, written or oral. These practices reduce consumer welfare and market efficiency by limiting competition. The implementing regulations specifically include four categories of practices that are deemed “per se violations”: (1) price-fixing or setting sales conditions; (2) blocking market access for certain firms; (3) dividing markets by geography, customer type, distribution points, or time; and (4) colluding in tenders or bids, except when joint bidding is transparently necessary for the project and does not harm competition.[97]

- Abuse of Dominance: Firms or groups holding a dominant market position (defined as having a 40% or greater share, or the ability to control market conditions like prices or demand) are prohibited from engaging in practices that restrict competition. Abuse can include actions like setting unfair purchase or selling prices, or limiting production to harm competitors. Specifically, the implementing regulations deem two cases “per se violations”: (i) when a firm either forces another firm to avoid certain business relationships or (ii) conditions the sale of its products on accepting unrelated obligations or goods. Such practices violate market fairness by distorting competition. [98]

Merger control regime

The KSA has a mandatory and suspensory pre-closing merger control system. The GAC requires notification of economic concentrations that meet its turnover thresholds and jurisdictional test.

The GAC’s guidelines require an economic concentration to comprise both (i) the transfer of ownership of a type specified in the guidelines or a joining of two or more managements and (ii) a change in control of one or more undertakings.[99] The guidelines mention (several times) that “undertaking” is a broader concept than the term “company”, and that the competition law is of “very wide application”.[100] Likewise, the GAC considers that “economic activity” is a “wide concept” that “refers to any activity consisting of offering products or services in a market” whereby it is “not necessary that the activity earns a profit or be intended to earn a profit”.[101]

In March 2023, the GAC doubled the notification threshold from c. USD 26.6 million to c. USD 53.3 million. Further amendments followed in November 2023, when the GAC introduced new local nexus thresholds. Accordingly, the GAC requires notification of an economic concentration (other than a joint venture where the old thresholds continue to apply)[102] if it meets all of the following cumulative conditions:

- the combined annual worldwide turnover of all parties exceeds c. USD 53.3 million (200 million Saudi Riyals),

- the target has at least a c. USD 10.6 million (40 million Saudi Riyals) annual worldwide turnover, and

- the combined annual Saudi turnover of all parties exceeds c. USD 10.6 million (40 million Saudi Riyals).[103]

As is evident from its guidelines, the GAC intends to follow “standard international practice”, explicitly referring to the “practice in the European Union and its Members States”.[104] The GAC will ask if the transaction will “have the effect or likely effect of substantially lessening competition in a relevant market”. The GAC’s test is forward-looking and will take into account market shares and concentration levels before and after the completion of the transaction.[105]

It would be challenging to obtain approval for a merger that reduces competitive constraints or incentives for competitive rivalry among the remaining market participants. This will be assessed on a case-by-case basis. The GAC will view a transaction as reducing competition if it results in an increased market power that changes the parameters of competition e.g., price, quality, range/variety etc., in a way that is detrimental to customers. However, only a “substantial” lessening of competition will be in contravention of the competition law.[106]

The increased notification threshold aims to reduce unnecessary merger control filings in the KSA and should therefore be viewed positively. However, the absence of a robust local nexus test means many foreign-to-foreign transactions still technically trigger filing requirements:

- Article 3 of the competition law states that it applies to “practices occurring outside the [KSA] that have an adverse effect on fair competition within the [KSA]”.

- According to its guidelines, the GAC will require economic concentrations taking place outside the KSA to be notified only where there is a “sufficient nexus” between the economic concentration and a market inside the KSA.

To fall within the GAC’s jurisdiction, a transaction’s “potential effect” must be “direct, substantial, and reasonably foreseeable” on competition in the KSA.[107] Importantly, the GAC will generally consider it sufficient if one or more of the foreign undertakings has sales in the KSA. “For clarity, a direct effect is not limited to direct sales and may take place by way of indirect sales (e.g., sales by way of a distributor).”[108] However, sales in the KSA are not necessary to establish a sufficient nexus with a market in the KSA. Ultimately, the GAC decides on a case-by-case basis the existence of a sufficient nexus to a market in the KSA. In case of doubt, the GAC encourages parties to approach it.[109]

From our experience, it typically takes about two and a half months to obtain clearance from the GAC if there are no substantial competitive concerns, but the precise timing varies depending on the number of requests for information (“RFIs”).[110] Also the experience and efficiency of the reviewer matter as well as whether the filing involves a “sensitive” sector such as pharmaceuticals, medical devices, or courier services, which typically receive more RFIs. The timelines for preparing an EU merger control filing and obtaining approval, particularly for complex transactions, are generally longer than in the KSA. In the EU, in-depth reviews often take several months to complete, and this does not account for the additional time required for pre-notification engagement with the European Commission (“EC”), which has no statutory time limits. By contrast, there is no equivalent pre-notification process in the KSA, streamlining the overall timeline.

There are two established routes to file with the GAC (in either case, there is no scope for any pre-notification):

- Short Form Filing (No-Objection Filing): The GAC introduced this expedited process without filing fees, in 2021. It involves completing an electronic form available on the GAC’s e-portal, which requires less information than the long form. Typically, the GAC issues its decision within 20 working days, subject to its assessment and the volume of RFIs.[111] Applicants usually annex a formal letter setting out the rationale for not submitting a long filing, g., emphasizing that the transaction will not result in a dominant market position or that the transaction does not involve a significant overlap in the KSA.[112]

- Long Form Filing (Economic Concentration Filing): This more comprehensive process requires the parties to complete a detailed form and additional submission formalities, including extensive commercial, financial, and marketing information, along with an economic report.[113] Upon submission, the GAC assesses the completeness of the filing and then issues an invoice for the filing fee. Once the fee is paid, a statutory 90-day review period commences, during which the GAC must render a decision.[114] If the GAC fails to decide within this period, the filing is deemed cleared. From experience, the GAC generally issues the invoice within two to three weeks and makes a decision within four to eight weeks post-payment, though this timing varies.

Unlike most countries in the Middle East that do not charge filing fees, the GAC imposes hefty filing fees for merger control notifications. The GAC calculates fees as 0.02% of the combined worldwide turnover of the parties, up to a capped maximum of c. USD 66,000 (which used to be almost double c. USD 106,000 until June 2023).[115]

Fines and enforcement activity

The GAC can impose fines of up to 10% of a company’s total global annual turnover or a fine of c. USD 2.6 million (i.e., 10 million Saudi riyals).[116] Alternatively, the GAC can decide to impose a fine not exceeding three times the profits gained in case of an antitrust infringement.[117]

Criminal sanctions are also possible but have to date not been imposed, likely being a last resort. The competition law also allows individuals or entities to take legal action if they can prove they have been harmed by a violation. Therefore, infringements of the Saudi merger control regime may face penalties from the GAC and civil action from affected parties.[118]

The GAC’s market surveillance unit monitors the international financial press (e.g., the Wall Street Journal, Financial Times, Bloomberg). Investigations therefore often involve transactions reported in the financial press and include at least one well-known company or brand. Additionally, as a member of the ACN, the GAC is notified of any filings made to other member authorities.

In early 2024, the GAC issued four circulars designed to increase competition law compliance:

- In February 2024, the GAC issued a circular stressing notification requirements and penalties for non-compliance under the merger control regime.

- In March 2024, the GAC issued three further circulars on (i) the consumer and economic benefits of enforcing antitrust and merger control laws, (ii) summarizing key legal prohibitions, and even (iii) urging the public to report violations.

Despite a whistleblower section on the GAC’s website, there is little public awareness. The GAC is addressing this, as, currently, the program lacks anonymity, requiring personal information, including an email address, to complete the form.

Another way the GAC stands out from (almost) all competition authorities in the Middle East is the fact that it publicly discloses its ever-so-increasing enforcement activities. Since 2009, the GAC’s annual reports have evolved significantly in length and detail, shifting from an Arabic-only publication to a bilingual Arabic-English publication in recent years, with the latest comprehensive reports containing extensive statistics on competition efforts and internal metrics. Along with Israel and Turkey, the GAC is only one of three competition authorities in the region that publish annual reports on their activities.[119]

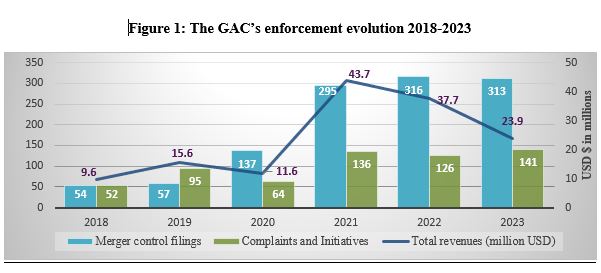

As illustrated by Figure 1 and in accordance with data from its annual reports, the GAC’s activity level has recently reached a peak:

- In 2023, the GAC received 313 economic concentration requests, 141 complaints and launched initiatives, and had a total of c. USD 23.9 million in revenues (including from fines imposed on competition law violators).

These statistics are impressive not only in comparison to other countries in the Middle East, but even when comparing to the EU. In the EU (which covers (now) 27 Member States), the number of merger control notifications also varies around 300–400 filing annually (i.e., in 2023, the EC received 356). On the other hand, and naturally so, the EC’s total competition-law related fines are well above those collected by the GAC.[120]

The fact that the GAC’s budget for 2022 (c. USD 26.6 million) was roughly 15% of the EC’s budget for 2022 (c. USD 176.8 million) highlights the significant difference in scale and resources.[121] Despite the smaller scale, the GAC’s budget is substantial relative to its national scope, suggesting a strong commitment to competition regulation within the KSA. To further contextualize this, the current population size of the KSA makes up not even 8% (c. 37 million people) of the EU’s (c. 449 million).[122]

The GAC first fined a foreign business in late 2020, penalizing PepsiCo and Al-Jamia Beverages Company Ltd. (each c. USD 2.6 million). The fines were later reduced to c. USD 1.35 million on appeal in 2022.[123] Since then, investigations have increased significantly. In 2022, the GAC carried out 299 dawn raids[124] (i.e., one dawn raid every business day) and conducted investigations on 126 companies (33 of which were indicted).[125] In 2023, the GAC further increased its enforcement activities, with 548 dawn raids conducted, averaging 2.2 raids every business day. [126]

Below we give some prominent and recent examples, which demonstrate that the GAC’s default approach is to levy the prescribed maximum fine of c. USD 2.6 million if it is not possible to estimate the annual sales:

- In February 2023, the appellate court in Riyadh upheld the enforcer’s highest-ever bid‑rigging fine of c. USD 2.6 million against Duja Jeddah Contracting, a company that colluded to rig a tender for construction services at a major domestic airport.[127]

- In April 2023, the appellate court in Riyadh upheld the GAC’s decision to fine 14 local cement makers a total of c. USD 37 million for colluding to raise prices and divide the market in the country.[128] The seriousness of the infringement is reflected in the fact that all 14 offenders received the maximum fine. This represents the GAC’s largest-ever cartel fine on 14 local cement makers for colluding to raise prices and divide the market.

- In June 2023, the GAC fined First Mills, a former state-owned flour producer c. USD 2.6 million for using exclusivity clauses in distributor contracts, a rare ruling on abuse of dominance. The infringement occurred before the company’s privatization in 2019 and thus demonstrates the GAC’s openness to also investigate and fine anticompetitive conduct by state bodies.[129]

- In July 2023, the GAC fined Saudi Gulf Environmental Protection Company, a Saudi waste management company c. USD 2.6 million for charging predatory prices, which barred rivals from entering the market.[130]

- In January 2024, the GAC filed charges against 79 establishments (automobile agents, distributors, and car showrooms) “for violations such as agreeing to fix prices and dividing markets according to geographic regions among others, which led to reducing competition and affecting the interests of consumers”.[131] The GAC decided to initiate criminal cases against 64 establishments and study settlement requests from the remaining 15 entities.

- On May 6, 2024, the GAC imposed individual fines ranging from c. USD 26,663 to c. USD 266,632 on several water bottling plants and commercial firms for colluding to fix prices and share customers.[132] On June 5, 2024, the GAC announced fines totaling nearly c. USD 4 million against six companies in the car and goods transport sector for violating the competition law by agreeing to increase transportation charges.[133] Both decisions are final following rulings by the competent court and illustrate the GAC’s focus on customer-facing enterprises.

- On June 13, 2024, the GAC granted judicial immunity to two establishments that disclosed partners involved in violations.[134] On June 14, 2024, the GAC initiated an investigation into alleged price-fixing among four breast-milk substitute product firms.[135]

Merger control-related decisions

The GAC has blocked two transactions since the adoption of the new merger control regime in late 2019, but only one on substantive competition concerns. Both prohibition decisions relate to acquisitions of Saudi consumer-facing companies:

- In December 2021, the GAC rejected German-based Delivery Hero’s planned acquisition of Saudi-based food delivery app, The Chefz, based exclusively on procedural grounds. The GAC said that the parties provided insufficient information to allow them to assess the transaction.[136]

- In February 2022, the GAC prohibited Saudi-listed National Gas and Industrialization Company (“GASCO”) from acquiring a majority stake in Saudi-based Best Gas Carrier Company, on substantive grounds, namely to prevent vertical integration. The GAC wanted to enhance competition, achieve general consumer welfare, and ensure an optimal distribution of resources in the economy. The proposed vertical integration would have enabled GASCO (who already has a monopoly of the gas supply chain) to become a leading player in offering liquid petroleum gas solutions.[137]

To put the high number of merger filings and the abovementioned prohibitions into context on average, almost half (40%) of the submitted merger control notifications to the GAC between 2021 and 2023 were deemed non-reportable. In 2023, the GAC approved 172 notifications, deemed 128 unreportable, and did not reject any application.[138] The GAC’s annual reports do not reveal why so many filings were deemed to fall outside the scope of the competition rules. The GAC’s 2021 annual report outlines three main criteria for a notification requirement: (1) turnover thresholds, (2) sufficient nexus with a market in the KSA, giving the GAC jurisdiction, and (3) change of control or control due to ownership transfer in one or more enterprises. We assume most filings were unreportable due to not meeting criterion (2), the jurisdictional nexus to the KSA. This is because, until November 2023, local nexus turnover thresholds were not part of the merger control test. Additionally, criteria (1) and (3) are delineated more clearly, whereas criterion (2) often requires case-by-case assessment by the GAC according to its guidelines.

When factoring in only the examined applications over the past three years, less than 1% of all transactions reviewed are prohibited (0.37%), confirming that rejections remain rare. By way of comparison, at EU level, the EC approved 322 transactions out of 356 in 2023, imposed commitments on 10, and only prohibited one.[139] Accordingly, also at EU level, less than 1% of deals are prohibited (0.5%) and c. 3% of deals were cleared conditionally in 2023.

In total, the GAC has conditionally cleared only four transactions: one in 2019 and three in 2023. This confirms the GAC’s increased use of remedies. Conditional approvals can include commitments from parties to maintain competitive prices, provide copies of agreements, and appoint monitoring trustees for compliance. The GAC usually imposes these for a period of three years:

- In November 2019, the GAC conditionally approved Uber’s c. USD 3.1 billion acquisition of UAE-based Careem’s mobility, delivery, and payments businesses. This transaction, initially notified under the pre-September 2019 competition law, was cleared under the current competition law, with Uber agreeing to eight behavioral commitments. These commitments included capping taxi ride prices, limiting surge rates, and allowing drivers to work for competitors. No divestment were required.[140]

- In May 2023, the GAC conditionally approved the c. USD 35.5 million acquisition of a majority stake in Direct Financial Network (“Direct FN”), a financial technology company, by Tadawul Advanced Solutions Company (“Wamid”), a subsidiary of Saudi Tadawul Group Holding Company (which also owns Saudi Arabia’s stock exchange). The commitments include ensuring fair pricing for goods and services provided by Wamid to Direct FN, non-preferential pricing for Wamid data supplied to Direct FN, and sharing copies of agreements between the parties with the GAC.[141]

- In August 2023, the GAC conditionally approved Arabian Contracting Services Company’s (also called Al Arabia)’s c. USD 276 million acquisition of rival Faden Media Agency. The GAC required Wave Media Company, a subsidiary, to be placed in a regulated fund. The remedies aim to keep the market open to new and expanding businesses. Al Arabia, the largest in the sector with over 60% market share, is partly owned by MBC Group. Faden Media is owned by Saudi royal Prince Abdulaziz Al Saud.[142]

- In September 2023, the GAC conditionally approved Jahez International Company for Information Systems Technology’s proposed 100% acquisition of The Chefz, but the transaction was never completed.[143]

Between September 2019 (when the new regime came into force) and early 2022, the GAC imposed gun jumping fines in four cases. By the end of 2022, this number rose to 15 and the GAC settled over 60 such cases.[144] The GAC’s 2022 annual report revealed that the information and communications and transformative industries sectors were the sectors where most unreported transactions were scrutinized.[145] Settlement cases rose to 39 in 2023. Indeed, in February 2024, for the first time under the new competition law, the GAC fined two Saudi companies Panda Retail Co. (a Saudi grocery retailing company) and Doorstep for Telecommunications and IT (each c. USD 107,000) for failure to notify their transaction during the pandemic.[146]

The GAC’s 2021-2023 annual reports illustrate a notable focus on certain sectors and violations. In 2021, the report noted a growing emphasis on abuse of dominance, particularly in the health insurance and automotive sectors. By 2022, one-third of the GAC’s complaints involved the wholesale and retail trade, along with the repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles.

In 2023, the GAC examined more than three-quarters of the complaints it received (i.e., dismissing only one quarter), with the wholesale and retail sectors making up 27.7% and the manufacturing sector 20.4%. The latest 2023 report highlights a significant focus on price fixing, both among competitors (horizontal) and in resale price maintenance (vertical), which accounts for nearly half of all identified violations. Furthermore, in 2023, the GAC investigated potential violations in the automotive, pharmaceutical, and poultry sectors. It also conducted sector-specific studies in the agriculture, fish, and construction markets.

Interestingly, the GAC’s 2023 annual report revealed a drastic rise in the number of exemption from competition law application requests, from one in 2022 and 2021 respectively, to 16 in 2023. It approved 10 requests. The vast majority of these requests were related to obtaining approval for closing deals prior to securing merger control approval (while the rest appeared to relate to obtaining comfort letters stating that antitrust rules do not apply). Also, these requests mostly pertained to the legal sector (38%), followed by the automotive and military industries (each making up 15%).

The GAC has investigated several foreign-to-foreign transactions for failure to file, with one case being prosecuted, though unsuccessfully, before the competition tribunal.[147] According to the 2022 annual report, the GAC received only 20 applications for joint venture projects, constituting 11% of the economic concentration requests in 2022. Joint ventures also only constituted 12% of the unreported deals investigated by the GAC in 2022. This suggest that the GAC’s enforcement appetite is first and foremost geared towards mergers and acquisitions and those entities that are active in the KSA.

Concluding remarks on the KSA

While the GAC’s efforts to publicize its activities are applaudable and unparalleled in the region, the GAC’s reports remain high-level and are not fully transparency on the reasoning behind the GAC’s decisions.

We keep monitoring the GAC’s practice closely and recommend clients to remain vigilant of the GAC’s heightened scrutiny of market practices and transactions when doing business in the KSA.

5. Deep-dive into the active UAE competition regime

Competition Committee – لجنة تنظيم المنافسة

The UAE introduced its first competition specific legislation Federal Law No. 4/2012 in 2012 to guarantee fair competition and combat monopolistic practices.[148] In 2014 and 2016, the UAE issued three implementing regulations that clarify certain substantive and procedural aspects.[149] Recently, the UAE revamped its competition law and enacted Federal Decree-Law No. 36/2023. The new law came into effect on December 29, 2023, replacing any conflicting previous rules (Article 39).[150] It similarly aims to stimulate the environment to “enhance effectiveness, competitiveness, consumer interest, and achieve sustainable development” in the UAE (Article 2).

This revision signifies a fundamental shift in the UAE’s approach to regulating its market and align it more closely with both international and regional trends. The latest ABLF Report upgraded the status of the UAE’s competition legislation from “Moderate” in 2020 to “Strong” in 2023. [151] As a reminder, this report was based on legislation up until August 2023 and therefore does not yet factor in the latest amendment of December 2023 and the additional regulatory changes anticipated in 2024.

Regulations, decisions, and laws established under Federal Law No. 4/2012, including the formation of the Competition Committee, remain effective until replaced in accordance with the provisions of the new competition law (Article 39). The Council of Ministers was meant to issue the implementing regulations by July 31, 2024 (within six months from the date of entry into force of the new competition law, January 31, 2024; per Article 38). However, this did not occur by the date of this article’s publication (December 2024) and it is unclear when the implementing regulations will be published.

At present, the primary regulatory authorities overseeing competition matters, including merger control, are the Competition Department and the Competition Committee, both under the Ministry of Economy (Articles 13-14 of the old law):

- The Competition Committee, chaired by the undersecretary of the Ministry of Economy, oversees UAE competition law policy. It advises the Minister of Economy on legislation, proposes competition policies, and reviews appeals of decisions.

- The Competition Department handles day-to-day law implementation, investigating anticompetitive behavior, evaluating exemptions, and coordinating with national and foreign authorities. The Ministry also acts as the Committee’s executive secretariat.

According to the new competition law, a “Competition Regulatory Committee” will be formed under the Minister’s supervision, with its structure and operations to be determined by a Cabinet decision based on the Minister’s proposal (Article 16). Similar to the old committee, the powers of this new authority include proposing policies to protect competition, studying implementation issues, recommending legislation, advising on exemptions, preparing annual reports, and addressing other competition-related matters referred by other authorities (Article 17).

The latest ABLF Report recommended that “the full independence of the Competition Committee should be guaranteed without interference or decision-making powers for the Ministry of Economy”.[152] The new authority however continues to operate under the UAE Ministry of Economy (i.e., only the Ministry of Economy has the competence to initiate investigations or respond to complaints).[153]

Broader competition law scope

The UAE’s competition law prohibits agreements between firms that restrict competition, such as price-fixing, territorial or customer allocation, limiting production, or collusive tendering, as these practices harm market efficiency and consumer choice (Article 5). It also prohibits dominant firms from using their position to unfairly disadvantage competitors, including through unfair pricing, limiting access to essential resources, tying sales to unrelated products, or obstructing market entry (Article 6). An establishment is considered dominant if it has the power, independently or with others, to control or influence a relevant market, with specific thresholds for dominance to be determined by the Council of Ministers and criteria for determining same forthcoming in the implementing regulations (Article 6(2)).

The new competition law expanded the list of prohibited abusive practices and introduced for the first time the concepts of “abuse of the position of economic dependency” (Article 7) and predatory pricing (Article 8). The latter prohibits establishments from setting prices below cost to drive competitors out of the market. The former prohibits exploiting an economic dependency without valid justifications, e.g., through unjust pricing, discrimination, coercion, refusal to deal, unreal prices, linked contracts, and market control. Both concepts appear to operate in addition to and independently of the “abuse of dominant position” concept (Article 6). By way of comparison, under EU law, both practices are primarily addressed under (and not separately from) the abuse of dominance concept.[154]

The new competition law applies to all entities involved in economic activities within the UAE and those overseas activities impacting the UAE market (Article 3). It broadly defines economic activity, covering “every activity primarily related to production, distribution, provision of products and goods, or performance of services in the State” (Article 1). Unlike the old law, there are no longer any exemptions for (i) small and medium establishments, (ii) all federal or local government entities, and (iii) those undertakings controlled or at least 50% owned by federal or Emirate governments (Article 4).

In line with the old law, any agreements, practices, or actions related to specific goods or services that are regulated by another law are excluded from the application of competition rules, as long as that law includes relevant competition provisions and is overseen by a sectoral regulatory body (federal or local). However, if the sectoral body requests and the Ministry agrees, the Ministry can take over regulation (Article 4).[155]

The key differences lie in the details: the new law no longer provides a specific list of automatically excluded sectors.[156] Instead, it places greater emphasis on the responsibility of sectoral regulatory bodies to manage “the rules and procedures for considering anti-competitive practices and cases of their exemption and Economic Concentration operations” (Article 4). This introduces more uncertainty for businesses that previously relied on clear exemptions. Without a predefined list of excluded sectors and further guidance, companies must now engage more actively with sectoral regulatory bodies and stay informed about the specific competition law provisions that may apply to them. This shift could lead to a greater need for legal consultation and a more proactive approach to compliance, as businesses navigate the potential overlap between sector-specific regulations and the broader competition law.

Also, certain exemptions may still be available on a case-by-case basis. For instance:

- Establishments owned by the federal or Emirate governments can still be exempt if a specific exemption decision is issued by the Council of Ministers or Emirate government respectively (Article 4).[157]