The Digital Markets Act (DMA) was initially designed according to a centralised system of enforcement. At least, that was the configuration the European Commission presented within its first draft of the regulation. During the legislative process, the DMA’s enforcement system slightly pivoted to a quasi-centralised system of enforcement. National competition authorities (NCAs) of the Member States regained some lost ground by being recognised with the power to support the European Commission in some of its enforcement actions.

My latest working paper precisely explores this interplay between the powers that national competition authorities may exercise in monitoring the DMA’s enforcement and the European Commission’s own role as the sole enforcer of the regulation, as recognised under Recital 91. The paper terms this shift as the decentralisation of the regulation’s enforcement system since we can observe a subtle reshuffling of the enforcement cards, away from the monolithic perspective of the EC as the DMA’s sole enforcer.

Two key arguments demonstrate this point. On one side, NCAs and other public bodies are called to cooperate and enhance the EC’s enforcement in a secondary and supporting role. Although we might think that the NCA’s role in enforcing the regulation’s provisions is unimportant, the letter of law demonstrates that they hold relevant powers in completing the EC’s enforcement strategy. On the other side, enforcement at the national level is not a one-sided matter where the DMA vests powers upon national authorities. The Member States have also taken it upon themselves to complete the regulation’s mandate by adopting legislative developments at the national level fleshing out some of the practical implications of the DMA in their territory.

National (competent) authorities steering the wheel of a ‘secondary and supporting’ role to the European Commission’s centralised approach

In principle, the EC is the DMA’s sole enforcer, given that it assumes all the regulation’s enforcement actions in a direct way. In most cases, the EC does have the last word on what enforcement strategy it wishes to pursue. However, when one has a closer look at the letter of the law, there may well be more authorities involved in the regulation’s enforcement.

At face value, the DMA does acknowledge the supporting and secondary role of national competition authorities (NCAs) in monitoring the regulation’s enforcement at the national level. Article 38(7) recognises this possibility by declaring that NCAs may monitor compliance with the obligations under Articles 5, 6 and 7 DMA at the national level. The DMA places two clear limitations to the exercise of these powers: i) the NCA must have sufficient competence and investigative powers to do so under national law, and ii) once those investigatory tasks are completed, the NCA must report its findings to the EC. Even though the provision is particularly aimed at providing the NCAs the adequate legal basis for those cases where it may not be completely whether the gatekeeper’s conduct breaches the DMA or antitrust rules, the regulation remains silent with respect to the need of the Member States to explicitly regulate those powers. In the second section of the post, we will come back to this same point, given that most Member States have responded in the same direction to this call.

Furthermore, NCAs are also recognised with the powers to conduct inspections or interviews at the national level when the European Commission requests it to, under Articles 22 and 23 DMA. In a similar vein, NCAs may receive complaints from third parties, business users or consumers regarding the gatekeepers’ violation of any of the provisions of the DMA under Article 27 DMA.

In any case, the reach of the national component within the DMA’s institutional framework is even larger. The DMA recognises different powers upon distinct public bodies, and not necessarily only upon NCAs. Different concepts are streamlined across the regulation, such as national authorities, national competent authorities, competent national competition authorities or competent authorities of Member States. At face value, the national component of the DMA’s enforcement crystallises into two main groups. First, the public authorities scattered across the Member States. Second, the Member States in themselves.

Within the first group of authorities with powers to enforce the DMA in some way or another, the regulation streamlines up to six different concepts. For instance, the DMA’s recognition of the monitoring of enforcement at the national level uses the concept of a ‘national competent authority of the Member State enforcing the rules referred to in Article 1(6) DMA’. In turn, Article 14(1) DMA mentions the concept of a ‘competent national competition authority’ under national merger rules, whereas Article 14(5) DMA references the term ‘competent authorities of the Member States’ as those which may use the information received under the DMA for the purposes of applying Article 22 EUMR.

From the six different concepts, there seems to be a clear predilection on the side of the EU legislator for a concept that one can easily associate with the concept of NCAs: national competent authorities of the Member States enforcing rules referred to in Article 1(6) DMA. Article 1(6) DMA establishes the complementarity between the application of EU competition law and the regulation. Complementarity stems, in the DMA’s own words, from the different legal interests protected under the regulation and antitrust rules. For the purpose of considering what authorities apply these rules, it seems as if only the competition authorities of the Member States in the sense of Regulation 1/2003 should be considered. Article 1(7) DMA follows upon the complementarity imposed under Article 1(6) by highlighting that the national authorities shall not take decisions which run counter to a decision adopted by the Commission under the DMA, transplanting the wording and sense of Article 16(2) of Regulation 1/2003 into the regulatory framework. Therefore, the designation of national competent (not competition) authorities applying the rules referred to in Article 1(6) DMA corresponds to the NCAs of each Member State. The most substantive provisions conferring powers upon national authorities use this concept, such as those instances where the authorities cooperate with the European Commission in conducting dawn raids on their own territory and their capacity to receive direct complaints or the power to conduct an investigation on non-compliance with Articles 5, 6 and 7.

This does not necessarily mean that NCAs are exclusively called to intervene within the DMA’s distribution of powers. Other national authorities, such as data protection supervisory authorities, consumer protection authorities, and national courts are also key to sustaining the DMA’s enforcement, although they may not seem like such apparent candidates stemming from the initial configuration of the DMA’s centralised system of enforcement. For instance, national courts must ensure that the regulation is applied consistently when faced with private enforcement claims at the national level based on violations of the regulatory instrument under Article 39 DMA. Furthermore, much-needed cooperation is needed between the European Commission and data protection supervisory authorities, since several of the DMA’s mandates are data-related obligations. One such example is that of the European Commission’s decision to open a non-compliance procedure for Meta’s potential violation of Article 5(2) DMA due to the introduction of its pay or consent mechanism as a technical implementation to the regulation (see a comment on the EC’s enforcement strategy here).

On top of this complex network of authorities intervening in the regulation’s enforcement, the Member States themselves are also called to play a major role in securing and futureproofing the DMA. For instance, according to Article 41 DMA, it is not up to the NCAs to ask for the European Commission to open a market investigation into the designation of a gatekeeper or to flexibilise the list of CPSs under Article 2 DMA. Member States are directly referenced within the provision, and they hold the powers to do so, not NCAs. Although in most cases the Member State’s (one could guess, the Ministry of Economy or Justice) views and approach towards enforcement and futureproofing the DMA may align with that of the NCAs, the competition authorities hold no say in securing the regulation’s prevalence.

Against this multi-dimensional enforcement framework, it was only reasonable to expect action on the side of the Member States in trying to flesh out what public bodies within their territory should enforce what provisions are in line with the powers vested in them by the DMA. And action we got.

The DMA legislative developments adopted at the Member State level

The DMA is a regulation. As with any other regulation, it is directly applicable in all the Member States. The regulation only addresses the need for transposition as far as the whistleblower tools and the potential application of collective action mechanisms are concerned (on the need for transposition, see here). Therefore, it is not entirely clear why most of the Member States (twenty-one out of the twenty-seven) have chosen to adopt (or propose) legislative amendments to complement the DMA via their national legal regimes. Only six Member States have chosen not to do so, namely Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Estonia, Lithuania and Portugal.

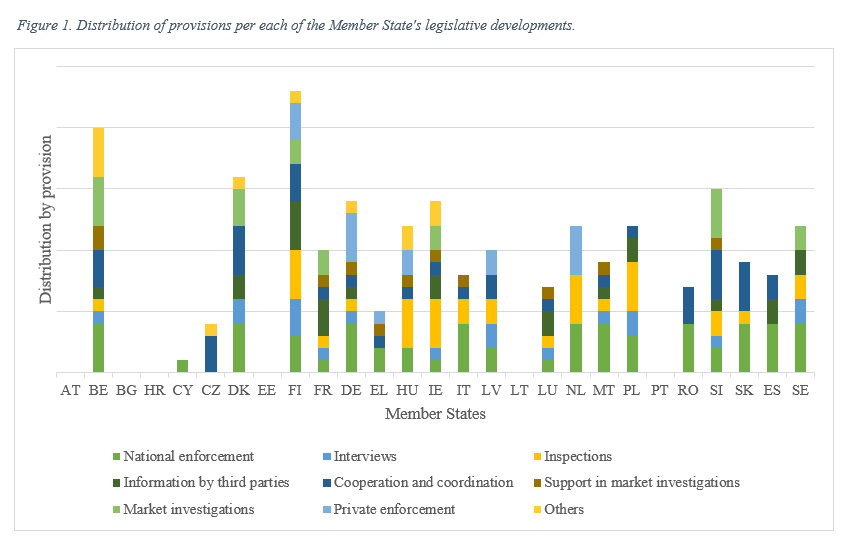

Given that none of the regulatory instrument’s provisions compel the Member States to transpose the powers into their legal regimes, each of them has chosen what powers it prefers to attribute its public bodies as if choosing from the range of provisions established by the DMA. One could guess that the Member States would especially focus on fleshing out the powers vested upon their NCAs via their monitoring capacity under Article 38(7) DMA since that is the most consequential provision impacting their capacity to directly apply the regulation’s provisions. On top of that, Article 38(7) DMA is the only provision within the regulatory instrument to require direct attribution of powers to the NCAs under national law. Few exceptions such as Cyprus or Romania have adopted these legislative developments for the particular purpose of granting those powers to their NCAs in isolation from any other provision. Most of the regulatory intervention at the Member State level tips towards the granting to the NCAs a vast array of powers. The most popular provisions to be fleshed out within the legislative developments are those related to the NCA’s assistance to the European Commission in conducting inspections at the national level as well as in the concretisation of the cooperation and coordination mechanisms set out under Article 38 DMA.

By this token, the legislative developments adopted at the Member State level move far away from being homogeneous in terms of their content. A high-level analysis of them shows a heterogeneous set of national laws that do not, in reality, add nothing new to the powers vested upon the NCAs, as shown in the figure below:

If one turns to the reality of the gatekeepers designated until now, the picture turns more black-and-white. The seven gatekeepers (Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Booking.com, ByteDance, Meta and Microsoft) hold different nationalities of origin, but they are based for their European operations in three Member States. All gatekeepers have established an Irish subsidiary of their parent companies for the handling of their EU operations, with the exception of Amazon, which is established in Luxembourg and Booking.com, with its establishment in The Netherlands.One can, therefore, expect most of the substantial enforcement at the national level to take place in these three Member States. For instance, it only seems reasonable that inspections will be conducted within the gatekeeper’s subsidiaries in those Member States. The application of Article 38(7) DMA will only concur in those cases where, for example, roll-out functionalities in some Member States and not others, but it seems as if those cases will be rare. Thus, it is especially important to know what those Member States’ stance has been in terms of adopting legislative developments to attribute some of their public authorities with powers to enforce the regulation’s provisions. Ireland and Luxembourg have already adopted amendments to this effect, whereas The Netherlands has not passed any legislative development relating to the granting of powers to its NCA (although it may be finally adopted in the near future since it was one of the first Member States to present a legislative development of this type). Therefore, it may well be the case that in the absence of a legislative development, the Dutch competition authority will not be able to assist the EC upon its request to conduct an inspection of Booking.com’s premises. In a similar vein, no legal path will be available to the EC to conduct such an inspection since the Dutch NCA will not have a legal basis sustaining a request for judicial authorisation to conduct such a dawn raid.

Furthermore, some of the Member States, such as Belgium, Finland and Ireland, have taken a preference to cover as wide a scope of action as possible, whereas others, such as The Netherlands, Romania or Spain have decided to interfere as little as possible with the EC’s enforcement action, given its role as the DMA’s enforcer. The divergence between the distinct legislative developments may entail that each of the NCAs draws upon the DMA’s provisions differently. Whilst some may stand as ‘activist’ NCAs in seeking to remain at the forefront of the DMA’s enforcement, others seem to be more preoccupied with the limitations that the regulation imposes upon them in their supporting role of enforcement.

In this context, the twenty-one legislative developments adopted (or proposed) at the Member State level contribute to the further decentralisation of the DMA’s enforcement system. This aspect may not be particularly harmful to ensure contestable and fair markets across the European Union, but it may undermine the other key objective of the regulation: to address fragmentation in the internal market regarding digital rule-making and enforcement.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Competition Law Blog, please subscribe here.