Introduction

Nowadays, it is not uncommon for Spanish courts to have to rule on disputes where there is uniformity in the facts and the applicable legal rules. In civil courts, mass litigation arose as a result of nullity suits filed by consumers in banking and financial matters regarding contracts for the subscription of banking products (preferred shares, subordinated debentures, swaps, etc.) and for the abusiveness of certain clauses incorporated in mortgage loans (floor, IRPH, multi-currency, early maturity, expenses, etc.) or in credit card contracts (usury). The proliferation of lawsuits stems from the scattering and fragmentation of potential plaintiffs in those cases. Lacking any adequate mechanism for consolidating actions, both plaintiffs and defendants have readily adjusted to this emerging landscape, further contributing to this trend.

Spanish Judges have adopted measures to “standardize” the judicial response to a plurality of repeated cases, even if this is detrimental to the judgment and individualized assessment of each claim. Frequently, the treatment prescribed by the courts for mass litigation resorts to equality as a response, the top Court in Civil And Commercial matters (Supreme Court chamber 1) has repeated in different contexts in which it have faced massive claims when deciding them: “the aspiration of justice is now connoted by the requirement to give equal or equivalent treatment to equal or equivalent situations, and to facilitate the predictability of judicial solutions in order to provide greater legal certainty to the market” (Honor protection-debtors’ lists: LG 2.2 of judgments of 11/3/24, ES:TS:2024:1324, ES:TS:2024:1322; LG 2.4 of judgment of 11/1/24, , ES:TS:2024:64; Revolving credit card-usury: LG4.4 of judgment of 15/2/23, ES:TS:2023:442; repeated in other judgments, ES:TS:2023:5478, LG 2.2; ES:TS:2024:833 and ES:TS:2024:746).

Thus, equal treatment of plaintiffs in analogous situations is prefered to safeguard legal certainty and give predictability to the judicial response. This standardization of judicial decisions is a pragmatic solution that guarantees their coherence, facilitating the judicial task against the tedium of resolving similar lawsuits individually, even if it is detrimental to a concrete assessment of the different arguments and the varied evidentiary efforts in each process. Until recently, the appeal to mass litigation as a special context whose efficient resolution requires an equal solution for a plurality of similar matters was concentrated in banking/financial and honor protection matters, but recently the Spanish Supreme Court has extended this treatment to claims for damages caused by the truck cartel.

Mass competition damages litigation

The Spanish Supreme Court’s response to the truck cartel damages claims can only be understood as the judicial reaction at the dawn of mass litigation of harm caused by anticompetitive conducts. The Court has decreed a standard response to these claims, inspired by the principle of equality. Exercising equal justice, the Court has resolved the downward standardization of damages awards. Several milestones can be identified in the evolution of the Court’s jurisprudence on the case:

- At first, the rulings on appeals from the “first wave” affirmed the entitlement of all claimants to receive a minimum compensation, irrespective of the inadequacy of their assessment of the overcharge.

- Subsequently, in more than two hundred orders handed down en masse, the Court has mechanically extended the above solution to a number of similar disputes.

- Finally, in the judgments handed down last march deciding a new batch of appeals, the Court subjected the claimants’ expert report to severe and rigorous criticism, revising the positive assessment that several appellate courts had made of it, and prescribed an equal solution for all claimants with reference to the rulings of the “first wave”.

Theoretically at least, it remains possible that in future rulings on this matter (including those resolving the claims filed against Scania) the Supreme Court could find other expert reports convincing. However, as long as this is not the case, the judicial estimate of the damage will be the same for all (i.e., 5% of the purchase price of the cartelized vehicle).

Right of every claimant to a minimum compensation: the “first wave” judgments

In its initial rulings on damages compensation in the truck cartel, the Supreme Court did not expressly allude to mass litigation. Even so, such character was present in the maritime reference to the courts’ facing “waves” of claims, an expression which was repeated in many of them.

In “first wave” rulings (here) the Supreme Court established the right to damage compensation of any claimant: the cartel caused harm to the purchasers of medium and heavy trucks, consisting in the payment of a surcharge over the price that would have resulted had the infringement not occurred. In addition, given the insufficiency and inadequacy of the calculation submitted by the claimants (not a proper expert report, but a collection of data and information “heavily inspired” by metadata studies on the harm caused by cartels), the Court ratified for all of them an estimate of the harm in 5% of the purchase price of the cartelized trucks (plus interest from the time of purchase). The Court ignored the manufacturers’ severe criticism of the pseudo-report submitted by the claimants, considering that: “the evidentiary activity deployed by the plaintiff, specifically the presentation of the expert report with the claim, despite the fact that said report is not convincing, in this case and in view of the state of the matter and of the litigation when the claim was filed, can be considered sufficient to rule out that the absence of sufficient proof of the amount of the damage is due to the plaintiff’s inactivity” (LG 6.24 of ES:TS:2023:2492, which is repeated in the remainder).

At that time, it remained to be seen what would happen with the claims based on true expert reports (here), when some of them had been considered convincing by a good number of Courts and (although some of them had reduced the proposed calculation due to inaccuracies or weaknesses detected). The Supreme Court has ruled on the matter in eight new judgments issued on March 14, 2024 that resolve appeals filed against the judgments of the Provincial Courts of Almería, Álava, Cáceres, Coruña, Oviedo, Valladolid, and Zaragoza (Table 1) which I will delve into in more detail later.

Table 1. Supreme Court judgments of March 14, 2024

| Nº | Rapp. | Reference | Parties | Judgment appealed | No. Trucks | At the end (5%) |

| 370/24 | Sancho | EN:TS:2024:1287 | Ttes. Gelado and Riesco v. MAN | Oviedo 23/11/22, ES:APO:2020:4760, Covián (8%) €25,855.32 | 4 | €16.150,57 |

| 372/24 | Vela | EN:TS:2024:1285 | E.S.G.. v. Renault | Zaragoza 20/4/21, ES:APZ:2021:1426, Martínez Areso (full) €23,465.23 | 1 | €3.906,58

|

| 373/24 | Sarazá | EN:TS:2024:1286 | Hormidesan v. Daimler | Cáceres 4/5/21, EN:APCC:2021:451

González Floriano (full) €172,555.28 |

6

concrete. |

€25.935,00 |

| 374/24 | Sarazá | EN:TS:2024:1288 | Excavations Pérez Lois et al. v. MAN | Coruña 8/2/21,EN:APC:2021:21 González-Carreró (2/3 amount claimed) €61558.22 | 5 | €21.155,03 |

| 375/24 | Candle | EN:TS:2024:1289 | Gilmartín Servicios Integrales et al v. MAN | Valladolid 11/3/21, EN:APVA:2021:357 Martin Verona (full) €56153.98 | 2 | €8.728,00 |

| 376/24 | Sancho | EN:TS:2024:1291 | Y v. Daimler | Oviedo 15/6/21, EN:APO:2021:2181

Soto-Jove (8%) €5769.71 |

1 | €3.606,07 |

| 377/24 | Sancho | EN:TS:2024:1292 | Transportes Viana v. Daimler | Álava 19/5/22, EN:APVI:2021:492 Villalaín (full) €120271,230 | 5 | €17.836,31 |

| 381/24 | Sancho | EN:TS:2024:1290 | F v. Renault | Almeria 6/4/21, roll 185/20, Calero, Dismissed | 1 | ND (€4,100) |

As will be seen, the issues being tried are the same in the first seven rulings (in all of them the claimant based his claim on the Caballer report), while the last one (ES:TS:2024:1290) exclusively examined the claim’s rejection by the Almeria Provincial Court due to lack of standing to sue the purchaser of a truck under a leasing contract (now it must take up the matter again to resolve the rest of the issues raised).

Mass decisions on cassation appeals: inadmissibility and express dismissal of appeals

One demonstration of how the Spanish Supreme Court is handling the mass litigation context resulting from the claims for damages caused by the truck cartel can be observed in the mass resolutions of appeals through writs and orders.

In fact, between the judgments of last June and those of March of this year, the Supreme Court has issued more than two hundred orders and rulings that definitively resolve the appeals filed: either upholding the appeals and reversing the appealed judgments, or rejecting the appeals, on the understanding that the issues raised had already been resolved in the judgments of June 2023. For the time being, all the orders upholding appeals refer to seventeen rulings of the Valencia Provincial Court that rejected claims on the grounds that they were time-barred (Table 2), which lead the Supreme Court to return the proceedings so that the Court of Appeals can rule again on the appeals.

Table 2. Supreme Court Orders (Rapp. Sarazá) upholding cassation appeals

| Date | ECLI | Parties | Plaintiff’s expert | Valencia Provincial Court Judgment |

| 5/2/24 | EN:TS:2024:1491A | Grupo Bertolín SA v. MAN | pseudo | 29/9/20 EN:APV:2020:3475 ( De la Rua) |

| 19/2/24 | EN:TS:2024:2131A | S v. AB Volvo | Zunzunegui | 24/11/20 EN:APV:2020:4272 (Martorell) |

| 19/2/24 | EN:TS:2024:2133A | Transbenifayo SL v. DAF | Pseudo | 9/12/20 EN:APV:2020:4789 (Andrew) |

| 15/4/24 | EN:TS:2024:4770A | PM v. DAF | Zunzunegui | 9/12/20 EN:APV:2020:4780 (De la Rua) |

| 5/2/24 | EN:TS:2024:1467A | B v. MAN | Naider | 9/1/21 EN:APV:2021:125 (Andres) |

| 19/2/24 | EN:TS:2024:2125A | V and JR v- Daimler | N.D. | 19/1/21 EN:APV:2021:157 (Martorell) |

| 19/2/24 | En:TS:2024:2129A | L v. AB Volvo | Zunzunegui | 2/2/21 EN:APV:2021:478 (De la Rua) |

| 19/2/24 | EN:TS:2024:2130A | Ttes. and Exc. Risueño v. Daimler | ND | 2/2/21 EN:APV:2021:471 (De la Rua) |

| 19/2/24 | EN:TS:2024:2127A | Xirvella Trans Rius et al v. MAN | ND | 16/2/21 EN:APV:2021:558 (De la Rua) |

| 19/2/24 | EN:TS:2024:2128A | Concret Union v. AB Volvo | Zunzunegui | 30/3/21 EN:APV:2021:929 (De la Rua) |

| 15/4/24 | EN:TS:2024:4771A | Concret Union et al v. MAN | Zunzunegui | 30/3/21 EN:APV:2021:950 (Pedreira) |

| 18/3/24 | EN:TS:2024:3537A | M v. Daimler | pseudo | 21/6/21 ES:APV:2021:2571(Pedreira) |

| 15/4/24 | EN:TS:2024:4768A | Ttes. J. Villaescusa v. MAN | Zunzunegui | 20/7/21 EN:APV:2021:3073 (De la Rua) |

| 15/4/24 | EN:TS:2024:4769A | Cementos La Unión v. AB Volvo | ND | 25/10/21 EN:TS:2024:4769A (Andrew) |

| 15/4/24 | EN:TS:2024:4767A | Transrocamar v. Renault Trucks | PQAxis | 3/12/21 ES:APV:2021:4863(Martorell) |

| 18/3/24 | EN:TS:2024:3539A | Transrocamar v. Volvo Trucks | PQAxis | 21/12/21 EN:TS:2024:3539A (Martorell) |

| 18/3/24 | EN:TS:2024:3538A | Transrocamar v. MAN | PQAxis | 25/1/22 EN:APV:2022:109 (Martorell) |

Although they are not published in CENDOJ, there are many inadmissibility orders of cassation appeals. In them, the Court deems that the issues raised by the appellants were resolved in the judgments of the “first wave”, closing the way to appeals against judgments handed down by several provincial courts (Murcia, Palencia, Pontevedra, Soria, and Valencia) that had followed only the judicial estimate of overcharge in 5% of the purchase price of the cartelized trucks. Surprisingly, perhaps by mistake, the Supreme Court has also issued a dozen rulings rejecting appeals filed against appellate judgments with higher estimates of the overcharge or even fully estimating the quantification presented by the plaintiff (Table 3).

Table 3. Supreme Court rulings rejecting appeals against estimates higher than 5%

(or judgments that fully upheld the claimant’s report)

| Judgment appealed | Date | Parts | Report | Reference |

| 15/10/20 (ES:APA:2020:3024) Soler | 22/11/23 | J. v. AB Volvo | pseudo | EN:TS:2023:15782A |

| 15/6/22 (EN:APAL:2022:1026) Calero | 10/4/24 | Trans Fernan SL v. Traton | PQAxis | 6393/22 |

| 23/4/21(ES:APVI:2021:105) Guerrero | 29/11/23 | X v. IVECO | Caballer | 4514/21 |

| 26/5/21 (ES:APCC:2021:544) González Floriano | 10/1/24 | JDM v. Daimler | Caballer | 7444/21 |

| 15/1/21 (ES:APSS:2021:1) Hillinger | 29/11/23 | Serbitzu Elkartea SL et al v. IVECO | Caballer | 3727/21 |

| 22/6/21 (EN:APVA:2021:960) Martin Verona) | 31/1/24 | Manuel Soto Rodriguez SL v. Daimler AG | Caballer | 8137/21 |

| 30/3/21 (ES:APZ:2021:864) Martínez Areso | 29/11/23 | Carreras Grupo Logístico SA v. IVECO | Caballer | 3948/21 |

| 30/3/21 (ES:APZ:2021:272) Martínez Areso | 29/11/23 | Frio Aragón SL et al v. IVECO | Caballer | 3941/21 |

| 30/3/21 (ES:APZ:2021:273) Martínez Areso | 13/12/23 | Pikolin SL v. IVECO | Caballer | 3928/21 |

| 16/12/21 (EN:APZ:2021:2724) Fernández Llorente | 14/2/24 | Transportes Callizo SA et al v. IVECO | Caballer | 1119/22 |

These rulings reflect the extensive activity of the Spanish Supreme Court in order to “massively” dispose of the appeals filed in cassation. The underlying procedural dynamics can be explained by the new regulation of civil cassation appeals introduced by Decree-Law 5/23, which introduced a change in the processing of appeals filed after its entry into force, in an attempt to accommodate the operation and processing of civil cassation to the “incessant increase in litigation“.

All of the above seemed to follow the idea -which, to a certain extent, was latent in the judgments of the “first wave”- that the Supreme Court would not review the evidentiary assessment made by the lower courts. Naturally, to the extent that the evaluation criteria of the hearings did not coincide, this implied the existence of disparate judgments depending on the court that resolved each appeal and the expert report used by the claimant. In some cases, with the same expert report for the quantification of the overcharge, claimants obtained different awards depending on the place where they had filed their claim. Although this disparity in the evidentiary assessment did not go unnoticed, given the repetition and the massive nature of the claims, the limitations of the cassation appeal procedure for the review of appellate judgments led to believe that the Supreme Court would not review the disparate evidentiary assessments of the lower courts (here).

Downward egalitarianism: the judgments of March 14, 2024

Considering the truck cartel damage claims as part of mass litigation requires standardized and uniform treatment for all claimants, an equal judicial response for all claimants. This provides legal certainty and predictability for the interested parties, facilitating the courts’ tasks and reducing litigiousness, as this should curb new lawsuits and reduce appeals. Since the outcome of the judicial dispute can be anticipated, it makes no sense for the parties to continue litigating (or appealing).

In order to reach the above situation, it was essential for the Supreme Court to correct any evidentiary assessment that had considered the expert report submitted by the claimants to be convincing. This explains why, in its second set of rulings on the matter, the Court corrects the evidentiary assessment of the lower courts. Its rulings place the principle of equality at its frontispiece:

“the present case, immersed in a broader phenomenon, that of mass litigation, which forces the reconsideration of the solutions usually adopted in another context of individual litigation, there are a series of circumstances that lead us, for the sake of the principle of equal treatment of that multitude of litigants (art. 14 EC), to enter into a minimal assessment of the suitability of the report submitted by the plaintiff for the accreditation of the overpricing” (reproduced in LG 7.3 EN:TS:2024:1287; LG 2.2, EN:TS:2024:1285; LG 4.2, EN:TS:2024:1286; LG 4.2 EN:TS:2024:1288; LG 3.2 EN:TS:2024:1289; LG 9.3 EN:TS:2024:1291; LG3.2 EN:TS:2024:1292).

In this context of mass litigation, the Supreme Court corrects the appellate courts’ assessment of the expert evidence because:

“It is an unavoidable reality that there are thousands of proceedings in which actions for damages are brought for the overcharge in the purchase of vehicles affected by the “truck cartel”, in which the same report provided in the present lawsuit by the plaintiff (prepared by Caballer, Herrerías and others) has been used to calculate the overcharge, without prejudice to slight adaptations. In all these cases, similar, if not identical, objections have arisen which, being predictable of all the reports provided, have been assessed in different ways by the courts of first instance: in some cases, these objections have been admitted, which has resulted in the court’s estimation, recognizing an evidentiary effort; in others, the acceptance of some of these objections has justified the court to make some adjustments to the report and modify its conclusions; and in others, the objections have been rejected and therefore the conclusions of the report have been accepted in their entirety. In this context, being as we were saying very similar the objections raised in all those lawsuits, this court of cassation, within its unifying functions of the judicial interpretation and application of the legal system (arts. 123.1 of the Constitution, 53 and 56 of the Organic Law of the Judiciary and 1.6 of the Civil Code), it cannot ignore the relevance of that disparity, which is not given by the singularity of what was judged in each case, but by the disparity of criteria of the courts of instance on the same questioned reality”

(reproduced in LG 7.3 EN:TS:2024:1287; LG 2.2, EN:TS:2024:1285; LG 4.2, EN:TS:2024:1286; LG 4.2 EN:TS:2024:1288; LG 3.2 EN:TS:2024:1289; LG 9.3 EN:TS:2024:1291; LG 3.2 EN:TS:2024:1292)

In order to safeguard the principle of equality, unlike what happened with the compensation for the damages in the paper envelopes cartel (in which the Supreme Court accepted different assessment criteria of the same expert report – and, subsequently, different damages awards – by the Madrid and Barcelona Courts, cf. ES:APM:2020:1 and ES:APB:2020:186), the Supreme Court now acts a judicial “third instance” that reviews the evidentiary assessment criteria of the Provincial Courts. To this end, it criticizes as illogical and erroneous their assessment of the expert report in the appealed judgments and then, to the extent that it had already ruled on the quantum of compensation in its “first wave” judgments, an extreme egalitarianism leads it to correct any alternative estimate, ignoring the claimant’s evidentiary effort.

Necessity of an equal assessment of the expert report: “en masse” correction of the error of the appellate courts

It is unusual for the Supreme Court to correct the assessment of evidence made by lower courts. In this case, moreover, it is a “mass” correction of the evidentiary assessment: more than half of the commercial courts that have ruled on truck cartel damages (42) and twenty provincial courts considered the Caballer report to be convincing. The purpose of this “mass correction” is to standardize the criteria for the evaluation of the expert report.

Based on the weaknesses and inaccuracies of the Caballer report (which it has, and I say this with confidence, as I have collaborated with lawyers who used it as a quantification in their lawsuits), its evaluation by the Supreme Court is presided over by the objective of giving equal treatment to all claimants who use it as a basis for their claims, regardless of the court before which they litigate.

The rigorous evaluation of the Caballer report by the Supreme Court contrasts with the benevolence that it dispensed to the pseudo-expert report in the judgments of the “first wave”. The High Court accepts the objections of the manufacturers, which leads it to discard it. It makes no sense, and it would be irrelevant for me to examine here the objections raised by the Supreme Court; in the end it is its decision that matters (“Roma locuta, causa finita“).

Even so, it is surprising that it considers illogical and erroneous the assessment of the report made by a multitude of lower courts and that it ignores the detailed reasons in the appealed judgments why the provincial courts considered the Caballer report to be convincing (e.g., A Coruña; LG 6 of ES:APC:2021:21; Zaragoza, LG 8 of ES:APZ:2021:1426; and Valladolid, LG 7 of ES:APVA:2021:357).

Apart from econometric juggling, given the temporal and geographical extension of the cartel (which limited the possible geographical and temporal comparisons), it is difficult to think of a better counterfactual to the cartelized market (medium and heavy trucks) than that of light trucks (and vans). In other jurisdictions with more experience in this type of claims, markets much further away from the cartelized market have been used for this purpose (KVR 66/08, Wasserpreise Wetzlar) without detracting from the comparability.

It is also striking that the Supreme Court has criticized that the calculation of the overcharge in the Caballer report is made “taking the gross prices of the manufacturers […] for its subsequent application to the final prices, without such automatic transfer being justified” when in other passages of the judgments it points out -responding to the manufacturers- “if we start from a gross price higher than the one that would have resulted from a competition not distorted by the cartel, the final price will also be higher” (LG 5.20, ES:TS:2024:1286; ES:TS:2024:1288, repeated in others). This is a gross contradiction, if one follows in its entirety the thesis on the “tidal effect” of the truck cartel (to which the Court referred in the “first wave” judgments) any change in gross prices is passed on to net prices (“it is as if the tide lifts all the boats. Each of the boats may keep rising and falling with the waves, but even the lowest boat is at a higher level and that’s the higher prices truck buyers pay“), without the “dispersion in discounts” altering that conclusion (here).

In the context of the truck cartel and with the difficulties involved in the quantification damages in this case, apart from the possible defects, I believe that the Caballer report is a “reasonable and technically founded hypothesis based on verifiable and not erroneous data” (LG 7.3, ES:TS:2013:5819). The rigor of the evidentiary requirement applied by the Supreme Court is excessive. In my humble opinion, it should be sufficient “to propose a hypothetical, but acceptable quantification“, “that is useful for the quantification of the damage, not that the proposed estimate is incontrovertible at all points“, “a minimally founded quantification, even if the judge has not granted it sufficient power of conviction” (as held by judge Eduardo Pastor “Actions ‘follow on’: the judicial estimate of the damage in the recent practice of Spanish case law” Revista Derecho Mercantil 317 (2020) 7). It was surely that same approach inspiring his assessment of the Caballer report, fully upholding the claim (e.g., ES:JMV:2019:1265, ES:JMV:2020:5922).

Finally, the Supreme Court seems to forget that in the proceedings in which the appealed judgments were issued, the Caballer report was the only attempt before the court to quantify the overcharge. In its severe criticism of the report, the Supreme Court departs from its own doctrine that “it is not enough that the expert report provided by the infringing party merely questions the accuracy and precision of the quantification made by the expert report carried out at the request of the injured party, but it is necessary that it justifies a better-founded alternative quantification” (LG 7.3 in fine, ES:TS:2013:5819).

Equality in the judicial estimation of the harm: 5% for all claimants

Having established the insufficiency and lack of conviction of the claimants’ expert report, the Supreme Court denies any possible judicial estimation of the harm that differs from the one it initially granted in the “first wave” judgments. No half measures are possible.

Until recently, several provincial courts modulated their estimation of the overcharge and the compensation awarded depending on the expert report submitted by the claimant, the Supreme Court has now ruled that there is no room for variations in the judicial estimation if the claimant’s quantification is not considered convincing. There is no room for variations in the judicial estimation based on different expert reports submitted by the claimants if they are not considered fully convincing, nor is it possible for the courts to consider any of the elements contained therein to reach alternative estimates (something that I had argued in the past, e. g., here and here). According to the Supreme Court, there is no deviation from this rule: “all other things being equal, the percentage shall be a common 5%” (LG 6.13 ES:TS:2024:1287 and LG 9.3 ES:TS:2024:1291).

On the other hand, in several of the appealed judgments, the Provincial Courts had estimated percentages higher than 5% of the trucks’ purchase price. The Supreme Court lowers all the estimates to that figure and orders that the judicial estimate be the same and, at least in this case, it will always be 5% of the purchase price “as long as it is not proven that there are extraordinary circumstances, specific to the case in question, that justify raising that minimum percentage” (LG 6.13 ES:TS:2024:1287 and LG 9.3 ES:TS:2024:1291).

In sum, despite the fact that the Supreme Court has emphasized the breadth and flexibility of the judges’ power to estimate the harm in these cases, it states unequivocally that this power cannot entail different estimates of the overcharge: if the expert reports are not accepted, the estimate of the damage must necessarily be the same for all claimants.

Judicial estimation “off the top of my head”

The judgments of the “first wave” upheld the judicial estimation of the harm as a power of the courts that existed before the Damages Directive. Now the Supreme Court clarifies that “the judicial estimate has to be reasonable and the parameters or circumstances that are claimed to be taken into consideration do not fulfil the function of verifying the exact appropriateness of the quantification, but serve to show that it is reasonable and not arbitrary” (LG 6.13 ES:TS:2024:1287 and LG 9.3 ES:TS:2024:1291).

The 5% of the purchase price that has become the preponderant judicial estimate of the overcharge of the truck cartel in the Spanish courts after several rulings of the commercial court 3 of Valencia (ES:JMV:2019:34 and ES:JMV:2019:187). As I have said before:

“This estimate has no quantitative link with the truck cartel, since it is based on qualitative references related to the characteristics of the infringement sanctioned by the Commission (duration of the cartel, concentration and market share of the cartelists, high amount of fines) and to the particularities of the cartelized goods, which are not very useful to inspire an objective quantification of the eventual damage (see Almacén de Derecho 5/12/20). Even if reluctantly, the common reference as ultimate foundation is the statistical information from academic metadata studies on the damage produced by other cartels collected in the 2013 European Commission Guide for the quantification of antitrust damages, pp. 48-49 (taken from the OXERA report, Quantifying antitrust damages towards non-binding guidance for courts, pp. 90-92). The use of this source for the quantification of the compensable harm (overcharge caused by the cartel) presents numerous problems, the most obvious being that what is included therein is a wide range of possible overcharges (ranging from 0% to 70%), thus laying the groundwork for disparity in any harm estimate using this source. […]

Without playing with numbers, and if one reads the explanations accompanying the table in the OXERA report and in the European Commission’s Guide: “in the case of European-wide cartels, which will be the ones affected by the European Commission’s decisions, it seems that presuming that the cartel, taking into account operational and detection costs, has not sought a profit of at least 10%, is a really conservative position as empirical evidence shows that the profit obtained is usually substantially higher” (as warned by the judgment of the commercial court 1 of Alicante of 4/3/22, PRR v. IVECO Spa, ES:JMA:2022:2175, par. 294 in fine).”

The 5% estimate was set in the absence of any attempt of quantification related to the case by the first claimants, extending in a standardized manner as a uniform parameter that is used to resolve successive claims regardless of the data and in the correctness of the models used by each of them” (Almacén de Derecho 11/22/22).

The Supreme Court affirms that the estimation of the overcharge at 5% of the purchase price of the cartelized truck is the foreseeable minimum (following “a generality of courts” and the Solomonic solution of the CAT in Royal Mail/BT in its only judgment in the case, which I commented here).

That was also the estimate accepted by the appellate courts that the Court ratified last year in the judgments of the “first wave”, with no more basis than the “good eye” (more poetically the commercial court 3 of Valencia, speaks of a “judicial estimate on the sky of luck“, par.165 ES:JMV:2022:9610). It is an imprecise and intuitive measure: neither little (“insignificant” or “merely testimonial” says the Supreme Court) but nor much (it is less than a third of what the injured parties usually claim).

Future competition damages litigation

The solution prescribed by the Spanish Supreme Court for the compensation of damages caused by the truck cartel exacerbates the principle of equality. In view of the impossibility of presenting a convincing quantification of the overcharge caused by the cartel, it provides the parties and the judges and courts with a uniform standard that gives an equal response to all claims. After last March’s rulings, there is little relevant else to expect from the litigation and appeals on this case; now it is possible to easily anticipate the judicial criterion, so it makes no sense for litigation to continue. It is true that the claims filed against Scania are formally different from the previous ones, but I do not see how a different solution can be reached with respect to them.

Finally, although the Supreme Court’s pronouncements are limited to damages caused by the truck cartel, some lessons can be drawn from them for other cases of mass tort litigation.

Lessons for victims/complainants

Since the calculation of the overcharge in many of these cases is very difficult and the Supreme Court has concluded that the judicial estimate of the damage must be the same for all those who do not make a convincing quantification, the incentives to invest in evidentiary efforts above the minimum established in each case are reduced. As I anticipated in a previous post: “any equal judicial estimate, which disregards variations in the evidentiary effectiveness of the claimants, deters any investment in evidentiary activity/effort. Obviously, that effect is exacerbated if what is extended to all claimants is the minimum estimate of the damage” (here).

In infringements such as the truck cartel in which “in addition to the difficulties inherent to the quantification of the harm in competition cases referred to in paragraphs 17 and 123 of the aforementioned Practical Guide, there are those derived from the special characteristics of the truck cartel” (LG 6.11 of ES:TS:2024:1287, repeated in the rest of the judgments), it makes little sense for the claimant to make an evidentiary effort above the minimum. Any additional effort will not bring him any benefit, since the judicial estimate will be unique, fixed, and equal for all claimants. This is the only realistic aspiration.

In addition, the minimum effort for the judicial estimation to proceed is determined by the assessment made concerning the first claimants (“prior tempore, potior aestimatio“). In the case of the truck cartel, given that the Supreme Court set a minimal effort in the “first wave” judgments, any investment above the price of the pseudo-expert report is a waste. It is unclear whether the criterion set then was due to a temporal circumstance (“the time when the claim was filed, so as not to fall into a retrospective bias“, par. 6.19 of ES:TS:2023:2492) or if it extends to those cases of modest amount of compensation claimed with respect to the cost of access to the data necessary for the calculation of the damage and the preparation of the expert report (par. 6.21 of ES:TS:2023:2492, “Disproportion that would make the plaintiff’s legal claim clearly uneconomical“). The latter seems to be the criterion according to most of the judgments that judicially estimate the damage in the automobile cartel (see here), well-illustrated in the affirmation by the Audiencia de Madrid that for the minimum damage to be estimated it is sufficient: “that the plaintiff has tried, with more or less success in the choice of the expert, to make a certain effort to reach a minimum standard of proof on the specific damage suffered and its quantitative scope” (FD6 of judgment of 7/21/23, Maqueda Gallego and Alvarez v. Toyota, ES:APM:2023:13066).

In the end, apart from the incentives in terms of the plaintiffs’ evidentiary effort (and the limitations introduced for its assessment in a context of mass litigation), fixing by judicial arbitration a minimum and conservative measure of compensation, completely disconnected from the harm, may have the serious effect of dissuading injured parties from pursuing claims, thus moving away from the objective of compensating the victims of the infringement.

Lessons for infringers/defendants

In view of the scenario drawn by the Supreme Court, the greater the difficulty in calculating damages, the more the infringers should invest resources in refuting the claimants’ expert reports and in arguing that the infringement did not cause harm (not in vain, the “no-harm infringement” is an all too common defense in the experience in Spain, see here). This investment is crucial in the initial phase, when the first claims are resolved (and when the plaintiffs’ expert reports are weaker), since what is decided then will affect the judicial standard to be projected in future decisions. Given the existing disproportion in the means and resources of the parties, the investment of resources by the infringers in proving the inaccuracies of the claimants’ expert reports will pay off, allowing the compensation fixed by the courts to be reduced to a minimum.

In the case of the truck cartel, manufacturers will compensate 5% of the purchase price of the cartelized trucks. Despite there are no compelling reasons to limit the estimate to that amount, that is the figure established by the Supreme Court for all claims. Moreover, it is unlikely that the judicial estimation of the overcharge in the claims against Scania will be different (it was the same cartel -see LG 2.2 of ES:TS:2024:1288-, the defendant’s report denies the existence of harm and the claimants’ reports are usually very similar, so they will not be considered convincing either).

In the end, to the extent that the solution adopted by the Supreme Court limits to a minimum and prudent overcharge (established by judicial arbitration) the maximum liability that infringers will have to face, it not only encourages them to invest resources in making this figure as low as possible, but also weakens the complementary function that compensation for damages should have to dissuade infringers from committing new infringements.

Takeaways for the judicial estimation of the harm

The judicial estimation of the harm needs to be the same for all claimants. No variation is possible according to variations in their evidentiary effort. According to the Supreme Court, the evidentiary effort cannot determine variations in the judicial estimation of the harm. It must lead to a figure -unique- resulting from the legitimate judicial discretion. Equality requires that it is not possible for different courts to make a different valuation of an expert’s report arriving at different judicial estimates. Nor are different judicial estimates possible with respect to different expert reports.

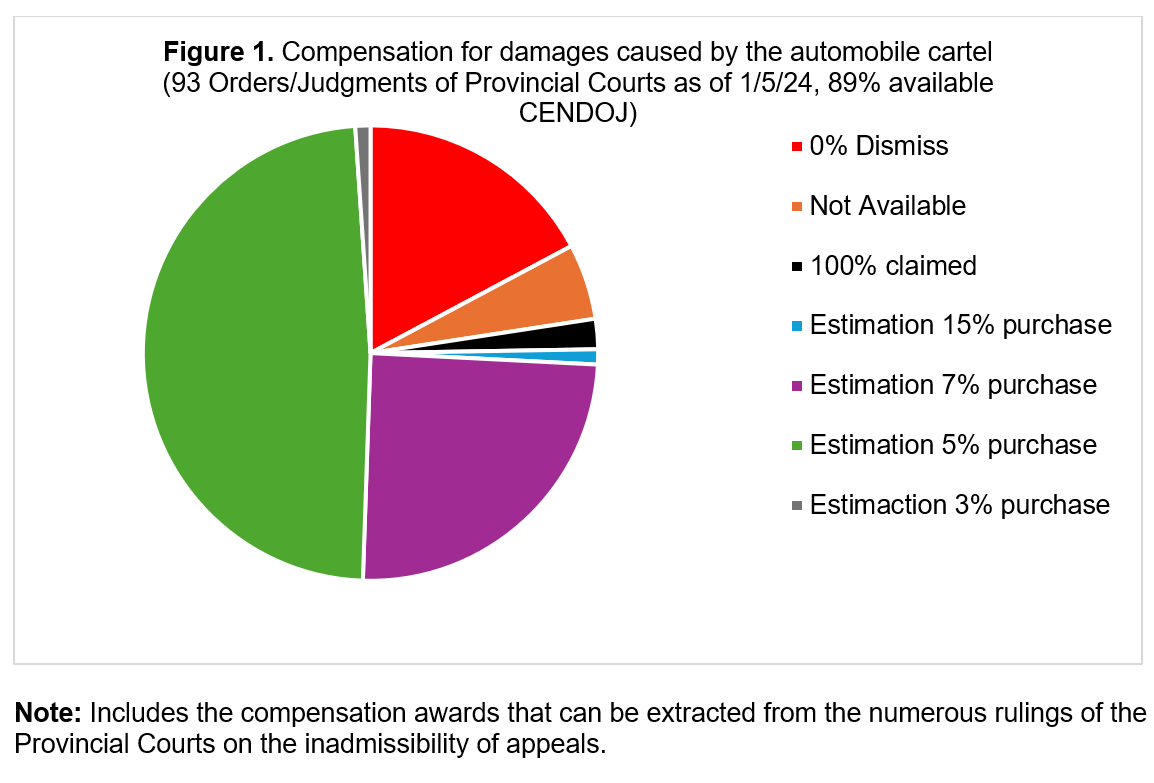

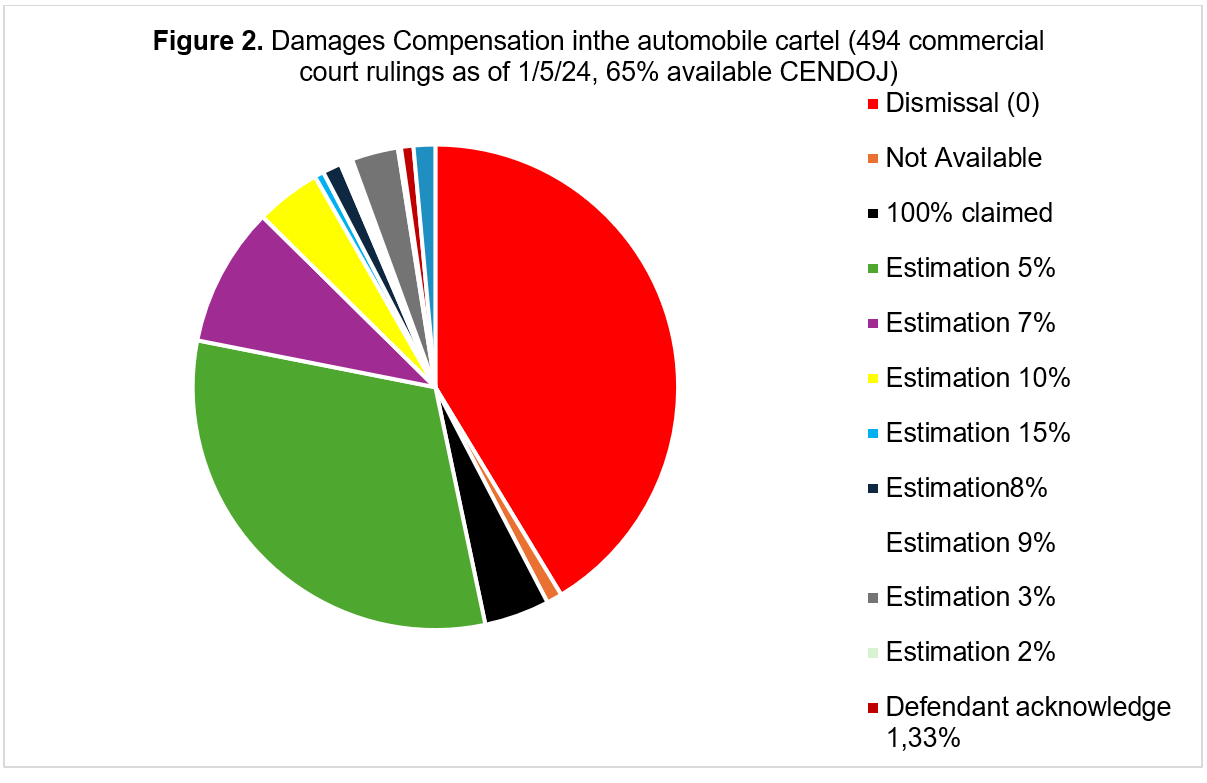

In addition, the 5% of the purchase price as a measure of compensation has a remarkable expansive power (even for other non-antitrust offenses, e.g. Dieselgate). That is the only possible aspiration of the victims in the truck cartel after the judgments issued by the Supreme Court on 14/3/24. Without any solid supporting basis, the estimation of an overcharge of 5% of the purchase price of the automobile is also the predominant one in the judgments on the damages caused by the automobile cartel (see figures 1 and 2 with the compensation awarded by more than 70 commercial courts and 17 Provincial Courts, although the particularities of the appeals due to the non-appealability of the commercial courts judgments make the situation more complex to assess).

Conclusions

As has occurred in mass litigation in other matters, the Spanish Supreme Court has practised equal justice in resolving claims for damages caused by the truck cartel. Given that there are thousands of litigations in which there are similarities in the facts and applicable rules, the prescription of a standardized and uniform solution ensures consistency and predictability in judicial decisions and provides legal certainty.

The Spanish Supreme Court has used the “broad brush” of the principle of equality in drawing the judicial response to the truck cartel damages litigation. Based on the rulings handed down by the Court last March, litigation, in this case, should decrease, as it is easy to anticipate the courts’ response: compensation of 5% of the purchase price of the cartelized truck for all claimants who make a minimum effort to quantify the overcharge.

Regardless of the solution given to this case, as I have outlined in the final part of this post, the “egalitarian tide” drawn by the Supreme Court provides undesirable incentives to claimants and infringers. This makes it difficult for private enforcement of competition law – at least in “mass litigation” – to serve the purpose of deterring infringement, facilitating the claims of injured parties, ensuring them full compensation for the harm suffered.

* The contributor serves as an academic consultant of CCS Abogados, the law firm representing claimants in the judgments herein commented. The views and opinions expressed in this post are his own, and do not necessarily reflect the position of CCS.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Competition Law Blog, please subscribe here.

The Spanish Supreme Court’s ruling on the truck cartel damages claims prioritizes equal treatment and standardized compensation. While this approach offers legal certainty and simplifies mass litigation, it raises concerns about the thoroughness of individual assessments and evidentiary efforts. This outcome underscores the need for legal practitioners to adapt their strategies in mass litigation, with claimants focusing on minimum evidentiary thresholds and defendants challenging expert reports early on. Ultimately, finding a balance between efficiency and individualized justice remains a challenge in these complex cases.