Below we cover the main competition law developments in Spain in 2023, concerning (i) institutions and legislation, (ii) antitrust, (iii) mergers, and (iv) State aid. The selection, as usual with these lists, is partly subjective.

Institutions and Legislation

Royal Decree-Law 5/2023 Reforms the Spanish Competition Law

On 29 June 2023, Royal Decree-Law 5/2023 approving a series of reforms to the Spanish Competition Act was published. The main amendments introduced by the reform were the following:

Changes to the time limits in procedures before the CNMC. In merger control proceedings, the duration of review under the simplified procedure has been reduced from one month to 15 working days (provided that a pre-notification draft was submitted to the CNMC prior to formal notification). The duration of the consultation process to determine whether a transaction is notifiable has been reduced from three months to one month and the duration of the in-depth review has been extended from two to three months from the date of the decision to initiate an in-depth/phase II investigation. With regard to infringement proceedings, the deadline to respond to the statement of objections and the draft decision has been extended from 15 days to one month and the overall duration of the investigation has been extended from 18 to 24 months.

Clarification of the CNMC’s role in collaborating with the European Commission (‘Commission’) in the enforcement of the Regulation 2022/1925 on the Digital Markets Act (‘DMA’) – a possibility which is legally foreseen in Article 38 DMA. The reform establishes that the CNMC may carry out investigations in Spain of potential violations of the DMA in Spain, provided it informs the Commission before adopting any formal investigative measure. In the context of these investigations, the CNMC is entitled to send RFIs, carry out inspections and use information received from third parties under Article 27 of the DMA. Respecting the exclusive competence held by the Commission to enforce the DMA, the reform clarifies that the CNMC shall not initiate or continue an investigation if the Commission initiated an investigation of its own based on the same facts. In any event, the CNMC shall share with the Commission the conclusions of its investigations and may use any findings to initiate a separate infringement proceedings under the Spanish Competition Act.

Streamlining of certain administrative procedures (for example, establishing that the draft infringement decision shall include the proposed sanction and an assessment of the evidence) and elimination of others (such as the report that the Competition Directorate had to submit to the Council of the CNMC once an infringement proceeding had been investigated).

The CNMC Approves Criteria Governing the Prohibition of Companies from Contracting with the Public Sector

On 13 June 2023, the CNMC approved the criteria applicable to the prohibition of contracting with the public sector. Such prohibition was introduced in 2015 in the national public procurement rules as a sanction that could be imposed on undertakings and individuals that have committed a serious competition infringement. National public procurement rules established that the duration and scope of such prohibition could be determined in the relevant CNMC infringement decision or via a separate procedure instituted by the Minister of Finance. As of the entry into force of Notice 1/2023 (the “Notice”), the CNMC will specify this in its decision, taking into account the nature of the infringement and the potential impact of the prohibition on the markets. The Notice sets out general criteria to determine the duration of the prohibition to contract with the public sector (which will be guided, among others by the seriousness and the duration of the infringement and its impact on the market with a maximum of three years established by public procurement rules), the products and services affected, the geographic scope of the prohibition (guided by the product and geographic market affected by the infringement, although narrower or wider depending on the circumstances) and the specific public administration / public sector entities with whom it is forbidden to contract.

Antitrust

The CNMC Closes Complaint against Amazon, Booking and TripAdvisor over False Reviews (Opiniones Falsas Plataformas)

The CNMC closed a complaint against Amazon, Booking and TripAdvisor and, therefore, decided not to initiate proceedings over a potential infringement of Article 3 of the Spanish Competition Act, which prohibits undertakings from distorting competition through unfair acts that affect public interest (Opiniones Falsas Plataformas, S/0053/19). The CNMC began to scrutinize the three platforms following a complaint received from the Organisation of Consumers and Users (‘OCU’) on November 26, 2019, alleging that they had carried out acts of unfair competition by publishing false reviews of their products and services on their websites.

Within these three platforms, users can publish reviews and opinions over the products or services sold or offered. Reviews and opinions allow consumers to form opinions about a product or service before consuming or purchasing them. Therefore, these publications constituted, in view of the OCU, a fundamental tool to evaluate the efficiency of these platforms.

The CNMC ultimately found that the publication of false reviews would, in any event, be carried out by third parties and thus, the alleged conduct could not be attributed to the platforms. The CNMC also analysed the various internal mechanisms to avoid the publication of false reviews and opinions and found that all three platforms had implemented reasonable and proportionate measures to counteract the issue, including mechanisms to delete false reviews and penalise profiles publishing them. Accordingly, the CNMC concluded that there was insufficient evidence of a potential infringement of Article 3 of the Spanish Competition Act and closed its investigation. However, the OCU provided evidence that sellers and intermediaries could contact users to incentivize them to publish fake positive reviews in exchange for economic compensation or by gifting them the product they intended to buy. As a result, the CNMC indicated that this conduct could violate consumer protection regulations and referred the complaint to Spain’s Directorate General for Consumer Affairs. This case illustrates the interconnectedness between competition and consumer protection issues.

The CNMC Imposes Second-Highest-Ever Fine on Apple and Amazon for Restricting Competition on Amazon’s Website in Spain (Amazon/Apple Brandgating)

The CNMC fined Apple and Amazon with c. €194 million for agreeing certain clauses in the contracts regulating Amazon’s conditions as an Apple reseller that affected the sale of Apple products on Amazon’s website in Spain by restricting competition from third-party resellers of these products and other products competing with Apple (Amazon/Apple Brandgating, S/0013/21). The fine on Apple amounts to €164 million, making it the highest fine that the CNMC has imposed on a single company, and the combined fine is the second highest ever after the CNMC’s 203.6-million fine on construction companies of 2022 (see D. Pérez de Lamo and X. Quer Zamora, KCL 2023, “Main Developments in Competition Law and Policy 2022 – Spain”).

According to the CNMC, first, Apple and Amazon agreed to restrict the number of re-sellers of Apple products on Amazon’s website in Spain by providing that only a limited number of distributors pre-selected by Apple would be allowed to sell Apple products (‘brand-gating clauses’). The CNMC found that up to 90% of re-sellers that had previously used the Amazon website for the retail sale of Apple products were excluded from the main e-commerce platform in Spain. Second, Apple and Amazon agreed to limit advertising space on Amazon’s website in Spain for products competing with Apple (‘advertising clauses’). When a user searches for a specific brand on Amazon’s search bar, products from competing brands appear too. The CNMC found that Apple and Amazon had agreed that, when a user searches for “Apple” on its search bar, only Apple products would be shown in the results page. Third, Apple and Amazon agreed to limit the possibility for Amazon to undertake marketing campaigns to customers who had bought Apple products on its website in Spain with competing products from other brands without Apple’s consent (‘marketing limitation clauses’).

The CNMC Fines Four Companies and Six Executives for Bid-Rigging Up to a 100 Public Contracts in the Defense Sector (Licitaciones Material Militar)

The CNMC fined four companies in the defence sector (Comercial Hernando Moreno Cohemo, S.L.U., Star Defense Logistics & Engineering, S.L., Grupo de Ingeniería, Reconstrucción y Recambios, JPG, S.A., and Casli, S.A.) and six of their executives for colluding in tenders of the Ministry of Defense concerning the supply, maintenance and modernization of military equipment (Licitaciones Material Militar, S/0008/21). The illicit agreements affected up to a 100 public contracts amounting to c. EUR 60 million, which mainly related to the maintenance of military vehicles and camping material. The sanctioned companies, along with the six executives, participated in a network of pacts including non-compete agreements, coordinated bids, and formed temporary joint ventures to ensure access to the tenders on an equal footing. The CNMC fined the four companies with EUR 6.2 million for two separate conducts, each constituting a single and continuous infringement of Article 1 of the Spanish Competition Act, and the six executives with individual fines ranging from EUR 34,000 to 60,000. In addition, the CNMC imposed a ban on contracting with the public sector as foreseen under Article 71.1.b) of Law 9/2017, of 8 November 2017, on Public Procurement on three of the four companies, subject to the State Public Procurement Advisory Board (‘SPPAB’) determining the scope and duration of the ban. Nonetheless, the CNMC positively noted the implementation of ex post compliance programs and requested that the companies refer back on the developments of these within six months, based on which the CNMC would potentially ask the SPPAB to impose a pecuniary penalty only. This precedent continues the CNMC’s firm track record against bid-rigging practices (see D. Pérez de Lamo, X. Quer Zamora and C. Rubio Bañeres, KCL 2022, “Main Developments in Competition Law and Policy 2021 – Spain”; see also D. Pérez de Lamo and X. Quer Zamora, KCL 2023, “Main Developments in Competition Law and Policy 2022 – Spain”).

Mergers

Transactional Activity and Merger Statistics

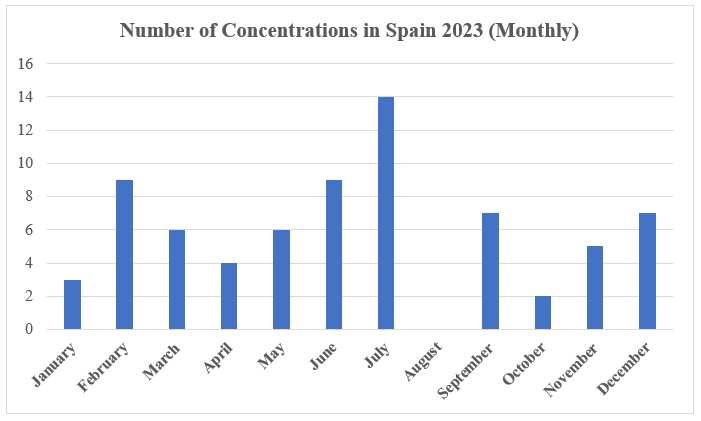

The CNMC reviewed a total of 72 concentrations in 2023, spread monthly as follows:

2023 was an average year in terms of transactional activity (see full list), which distances from the record 108 concentrations that the CNMC reviewed in 2021 (see D. Pérez de Lamo, X. Quer Zamora and C. Rubio Bañeres, KCL 2022, “Main Developments in Competition Law and Policy 2021 – Spain”).

The CNMC authorized the vast majority of concentrations in phase I without commitments (64); a minority of concentrations in phase I with commitments (3) and in phase II with commitments (2); and closed a few notifications before concluding the administrative procedure (3). The three concentrations authorized in phase I with commitments were Ebiquity / Mediapath (C/1406/23), Wonderbox / Smartbox (C/1361/22) and Alcampo / Activos Día (C/1363/23). The two concentrations authorized in phase II with commitments were Logista Publicaciones / Distrisur (C/1348/22) and Grimaldi / TFB (C/1305/22).

The CNMC Triggers Commission Review of Qualcomm / Autotalks under Art. 22 EUMR

The CNMC, alongside the Belgian, French, Italian, Dutch, Polish and Swedish Competition Authorities, initially requested the Commission to review Qualcomm’s acquisition of Autotalks under Article 22 of the EU Merger Regulation (‘EUMR’) (see CNMC Press release of 22 August 2023). Another eight competition authorities joined the request and the Commission accepted the referral on 17 August 2023 (M.11212). Qualcomm is a US multinational operating in the development and sale of semiconductors and software. Autotalks is a company specialising in automotive semiconductors.

State Aid

While State aid is European, there were a number of noteworthy judgments from the EU Courts with an important “Spanish component”, namely (i) Lico Leasing (C‑649/20 P, C‑658/20 P and C‑662/20 P), (ii) Spanish Goodwill (T-826/14, T-12/15, T-158/15 and T-258/15, T-252/15 and T-257/15, T-253/15, T-256/15 and T-260/15) and (iii) EDP España and Naturgy v Commission (C‑693/21 P and C‑698/21 P).

The Court of Justice Concludes Decade-Long Litigation Over the ‘Spanish Tax Lease System’ (Lico Leasing)

In 2011, following complaints, the Commission opened a formal investigation against a Spanish Tax Lease System (‘STLS’), which essentially enabled shipping companies to purchase ships built by Spanish shipyards at a 20-30% rebate (SA.21233). In 2013, the Commission concluded that three out of the five tax measures conforming the STLS amounted to State aid under Article 107(1) TFEU and declared them illegal and partially incompatible, thus ordering Spain to recover the advantages (Commission Decision of 17 July 2023, hereafter, the ‘Decision’). The Commission found that the SLTS granted an advantage to economic interest groupings (‘EIGs’) and their investors, which then partly transferred the advantage to shipping companies that purchased a new ship.

Spain, Lico Leasing SA and Pequeños y Medianos Astilleros Sociedad de Reconversión (‘PYMAR’) lodged actions for annulment against the Decision. In the first ruling of the Lico Leasing saga in 2015, the General Court upheld the applicants’ arguments that the Commission had erred in concluding that the aid was selective (Spain and Others v Commission, T-515/13 and T-719/13).

The Commission appealed to the Court of Justice, which set aside the General Court’s ruling in 2018, finding, in particular, that the General Court had erred in applying the concept of selectivity, and referred the cases back to the General Court to rule on the matter and the remaining pleas (Commission v Spain and Others, C-128/16).

In 2020, the General Court dismissed the actions for annulment lodged by Spain, Lico Leasing and PYMAR (Spain and Others v Commission, T-515/13 and T-719/13 RENV). In particular, the General Court found that (i) the STLS was selective insofar it granted broad discretionary powers to the Spanish tax authorities when applying the tax scheme (paras. 88-102), and (ii) the Commission did not err in ordering the recovery of the tax advantages from the EIGs and their investors alone, even if the tax advantages had been partly transferred to the shipping companies (paras. 127-132). In addition, the General Court dismissed the applicants’ arguments that the Commission had failed to state reasons, infringed of the principles of equal treatment, legitimate expectations and legal certainty in ordering the recovery of the aid.

Spain, Lico Leasing, PYMAR, and 29 other entities that had intervened in the first appeal before the Court of Justice, appealed again the General Court’s renvoi judgment to the Court of Justice. On 2 February 2023, the Court of Justice dismissed all grounds of appeal except one (failure to state reasons on the identification of the beneficiaries of the STLS for recovery), and gave final ruling on the cases, annulling the Decision in part (Spain and Others v Commission, C‑649/20 P, C‑658/20 P and C‑662/20 P). Regarding the assessment of selectivity, the Court of Justice recalled that discretionary aid measures confer a selective advantage (paras. 48 and 57). Accordingly, the three-step methodology (i.e., reference framework / difference of treatment / justification) to assess whether a tax measure of general nature confers a selective advantage is not applicable to the STLS (para. 48). The relevant national law – as interpreted by the Court and not having been contested in time by the applicants (paras. 65-67) – afforded significant discretion to the tax authorities when applying the STSL and, therefore, granted a selective advantage (paras. 58-60). The Court also rejected that the General Court had to examine whether the exercise of discretion by the Spanish tax authorities actually granted a selective advantage (paras. 63-64). Regarding the definition of the beneficiaries in the recovery order, the Court of Justice found that the General Court had provided insufficient reasons to reject the appellants’ challenge that the STLS transferred the advantage from the EIGs and their investors to the shipping companies (paras. 117-120). In particular, the General Court merely indicated that the Decision had identified the EIGs and their investors as the beneficiaries of the aid and that this finding was not disputed; the Court of Justice, however, found that such a challenge was necessarily implicit in the applicants’ arguments (para. 118). Accordingly, the Court of Justice set aside the judgment of the General Court and gave final ruling on this point, finding that it was apparent from the Decision, and the rationale of the STLS, that the latter intended to transfer part of the advantage also to the shipping companies and not just the EIGs and their investors (paras. 131-139).

The General Court Gives Another Twist to the ‘Spanish Goodwill’ Saga

In late 2001, Spain introduced a provision in its Corporate Tax Law providing that in the event an undertaking taxable in Spain acquires a shareholding greater than 5% in a non-resident company and retains it for at least one year, the resulting goodwill may be deducted via amortization from the taxable base. However, that deduction did not apply to acquisitions of shares in Spanish companies. The Commission found that this difference amounted to illegal and incompatible State aid because it conferred an unjustified advantage to Spanish companies in the context of competitive takeover bids (SA.22309). The Commission thus ordered the recovery of the aid in its decisions of 2009 and 2011. These decisions were extensively litigated before EU Courts for a decade, concluding with two highly relevant judgments of the Grand Chamber of the Court of Justice versing on the concept of selectivity, where the Court essentially found that a derogation from the reference framework, despite its ‘general’ scope, may still be selective if it favours some undertakings vis-à-vis others (see D. Pérez de Lamo, X. Quer Zamora and C. Rubio Bañeres, KCL 2022, “Main Developments in Competition Law and Policy 2021 – Spain”). The actions brought against the Commission decisions of 2009 and 2011 were thus unsuccessful.

In 2014, the Commission adopted another decision where it assessed a new interpretation of the tax scheme by the Spanish authorities in the form of a binding opinion, and concluded that this interpretation extended the possibility of deducting financial goodwill to indirect acquisitions of shareholdings in non-resident companies, which amounted to new aid, and thus declared it illegal and incompatible (SA.35550). Spain and multiple companies challenged the Commission’s 2014 decision. The General Court stayed these cases pending the outcome of the first litigation proceedings mentioned above, which concluded in 2021. On 27 September 2023, the General Court annulled the 2014 decision, finding in essence that the indirect acquisitions of shareholdings were already covered by the 2009 and 2011 decisions (T-826/14, paras. 51-67), and therefore, in adopting the 2014 decision, the Commission had withdrawn two valid decisions that conferred a legitimate expectation on Spain to implement the tax scheme (even if declared incompatible), and on private operators not to have to repay part of the illegal aid (T-826/14, paras. 77-81). Accordingly, the General Court annulled the 2014 decision in its entirety (T-826/14, para. 82).

The Court of Justice Defines the Obligation to Reason the Selectivity of an Aid Measure when Opening a Formal Investigation (EDP España and Naturgy v Commission)

In 2007, Spain established a ‘remuneration for capacity’ scheme aimed to promote investment in the production of electricity, which included an ‘environmental incentive’ for coal-fired power stations to install new sulphur oxide filters to reduce emissions.

In 2015, the Commission launched an investigation into the capacity mechanism market in multiple Member States. In 2017, the Commission initiated a formal investigation into the Spanish environmental incentive scheme (Commission decision of 27 November 2017 in SA.47912).

In 2018, Naturgy Energy Group (‘Naturgy’), an undertaking involved in the generation of electricity through coal-fired power stations, among others, which benefited from the Spanish incentive scheme, challenged the Commission’s decision to open a formal investigation (T-328/18). EDP España, another beneficiary of the Spanish incentive scheme, intervened in support of Naturgy. Naturgy argued, among others, that the Commission had infringed its duty to state reasons concerning the selectivity of the Spanish environmental incentive scheme. The General Court dismissed Naturgy’s action recalling that the decision to open the formal procedure may be limited to summarizing the relevant issues, including a preliminary assessment of the qualification of the measure as State aid, and explaining the doubts as to its compatibility with the internal market (T-328/18, paras. 60-65). In particular, the General Court concluded that the Commission had sufficiently reasoned why the Spanish incentive scheme favoured certain coal-fired power plants over others or over power plants generating electricity from other technologies (T-328/18, paras. 68-74). The General Court noted that “if the arguments of the applicant and the interveners were to be accepted, […] this would result in the blurring of the boundary between the decision to open the formal examination procedure and the decision to close that procedure” (T-328/18, para. 74).

Both Naturgy and EDP España appealed the judgment of the General Court (C‑693/21 P and C‑698/21 P). The appellants argued that the standard to state reasons is the same for the Commission regardless of whether the decision adopted opens or closes the formal investigation procedure, relying on Comunidad Autónoma de Galicia and Retegal v Commission (C‑70/16 P), and that the General Court had erred in discarding this precedent as irrelevant. The appellants argued further that the Commission has the obligation to assess the selectivity of the measure by analyzing the comparability of the beneficiaries with other entities pursuant to Commission v Hansestadt Lübeck (C‑524/14 P). The Court of Justice found that, even if, in a decision opening a formal investigation procedure, the Commission undertakes a preliminary assessment of the relevant measure, the Commission has to determine whether the aid measure constitutes State aid (C‑693/21 P and C‑698/21 P, para. 64). As the qualification of the measure as State aid deploys legal effects, including the suspension of the measure and the duty for national courts to draw the appropriate conclusions in case of infringement of the said standstill obligation, the Commission is required to disclose its reasoning “in a clear and unequivocal fashion” (C‑693/21 P and C‑698/21 P, paras. 65-67). The Court of Justice also found that, contrary to the General Court’s findings, (i) the precedent Comunidad Autónoma de Galicia and Retegal v Commission was relevant, even if it concerned the duty to state reasons for the Commission in a decision closing a formal investigation procedure; and (ii) the Commission was obliged to undertake the comparability analysis pursuant to Commission v Hansestadt Lübeck (C‑693/21 P and C‑698/21 P, paras. 68-72). However, none of the above was clear from the General Court judgment and the Commission 2017 decision (C‑693/21 P and C‑698/21 P, paras. 73-78). Accordingly, the Court of Justice set aside the judgment of the General Court and annulled the Commission 2017 decision to open the formal investigation procedure (C‑693/21 P and C‑698/21 P, paras. 82-84).

*The views expressed are our own and do not reflect the views of our employer/firm.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Competition Law Blog, please subscribe here.