The EU Artificial Intelligence Act (EU AI Act) is a landmark EU-originated legislative proposal to regulate artificial intelligence based on its potential to cause harm. Therefore, it can also be labelled as a risk-based regulation, meaning that the regulative burden and duties increase with the specific AI systems’ potential to cause harm.

For close watchers of the EU AI Act, May 2023 has been remarkable, as the European Parliament (EP) has officially finalized its position to enter into the so-called trilogues with the European Commission and the Council of the European Union (the Council).

The EU AI Act categorizes AI systems based on their likelihood to cause harm, and most of the regulatory duties are brought upon the high-risk AI systems. Although this categorization answers ‘which’ AI systems are regulated, there is another question at the same level of importance: ‘who’ will be held liable for a lack of compliance with the EU AI Act.

The EU AI Act puts the main burden on ‘providers’ who are the developers of AI systems and who “have an AI system developed with a view to placing it on the market or putting it into service under its own name or trademark, whether for payment or free of charge”, as articulated by the Article 3 of the proposed EU AI Act . However, there is another group of providers who are more numerous and are the key to ensuring the safe and fair use of AI systems: users, or (with the new name given by the EP) AI deployers.

In this blog post, I will provide a short analysis and summary of how entities who would deploy high-risk systems (deployers) will be regulated (or not) by the EU AI Act.

Firstly, who is a deployer in the EU AI Act?

Article 3 of the proposed AI Act, dating back to 21 April 2021, defined who qualified as a user of an AI system as follows: “user means any natural or legal person, public authority, agency or other body using an AI system under its authority, except where the AI system is used in the course of a personal non-professional activity”.

The EP’s compromised EU AI Act text (the EP version) coined users as deployers, given that the term could create confusion, as in most cases users are not responsible for the compliance of certain products. The definition has not changed except for the naming in the EP version of the EU AI Act. Therefore, for the remainder of this blog post, I will use the term deployer when referring to those who will use AI systems for professional purposes.

It is very important at this stage to state that the users of the high-risk systems will outnumber those who produce and provide high-risk AI systems due to the complex and demanding nature of AI development. Therefore, your work organization, future employer, banks, and even supermarkets can qualify as users under the upcoming EU AI Act if they want to deploy high-risk AI systems.

Little focus has been given to their responsibilities until now, although they will have a big part in ensuring and monitoring compliance with the EU AI Act and preventing harm arising from AI systems.

What is a high-risk AI system in the EU AI Act?

Article 6 of the proposed EU AI Act provides its methodology to regulate high-risk AI systems. High-risk AI systems are subject to a group of strict obligations including a detailed certification regime, but are not deemed so fundamentally dangerous that they should be banned.

This group of AI systems include:

- AI systems intended to be used as a safety component of a product, or themselves a product, which is already regulated under the NLF (e.g. machinery, toys, medical devices) and other categories of products harmonised EU law (e.g. boats, rail, motor vehicles, aircraft, etc.). (Annexes II-A and II-B).

- In Annex III [1], an exhaustive list of eight high-risk AI systems, comprising:

- Critical infrastructures (e.g. transport) that could put the life and health of citizens at risk;

- AI systems intended to be used for biometric identification of natural persons;

- Educational and vocational training, that may determine the access to the education and professional course of someone’s life (e.g. automated scoring of exams);

- Employment, workers management and access to self-employment (e.g. automated hiring and CV triage software);

- Essential private and public services (e.g. automated welfare benefit systems; private-sector credit scoring systems);

- Law enforcement systems that may interfere with people’s fundamental rights (e.g. automated risk scoring for bail; ‘deep fake’ law enforcement detection software; ‘pre-crime’ detection);

- Migration, asylum and border control management (e.g. verification of the authenticity of travel documents; visa processing);

- Administration of justice and democratic processes (e.g. robo-justice’; automated sentencing assistance).

- The Commission can add new sub-areas to Annex III through a delegated act if they pose an equivalent or greater risk than the systems already covered, but cannot add entirely new top-level categories.

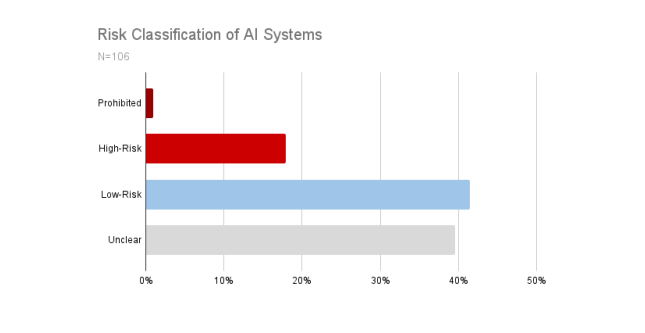

It is important to note that the classification in the EU AI Act comes with confusion. According to a study conducted by appliedAI Initiative GmbH among 106 selected AI systems, only 18% certainly qualify as high-risk and nearly %40 are yet to be defined or subject to the final text’s interpretation.

AI Act: Risk Classification of AI Systems from a Practical Perspective, appliedAI.

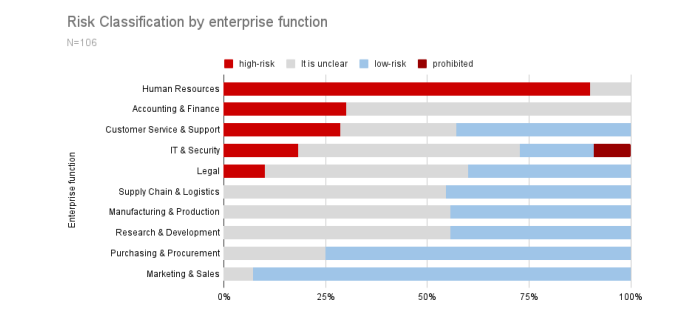

Most of the high-risk AI systems in the proposed EU AI Act fall under HR, Accounting and Finance, Customer Service and Support, IT Security and Legal categories.

AI Act: Risk Classification of AI Systems from a Practical Perspective, appliedAI.

Deployers: What do they have to comply with?

The proposed AI Act regulated the obligations of deployers when a high-risk system is used by them, mainly in Article 29. According to Article 29 of the proposed EU AI Act, deployers would have to;

- Use the high-risk AI systems in accordance with the instructions of use, issued by the providers;

- Would have to comply with sectoral legislation, if any other act of Union law is applicable when deploying a high-risk AI system (e.g. a bank may have to comply with additional approval or control over a loan-system support AI system);

- Ensure that the input data is relevant in view of the intended purpose of the high-risk AI system when the user controls input data;

- Monitor the high-risk AI system’s compliance with its own terms of use and suspend/report its use when they have identified any serious incidents within the meaning of Article 62;

- Keep the logs of the AI systems in an automatic and documented manner;

- Conduct a Data Protection Impact Assessment for the use of the relevant system.

Similarly, under Article 52, deployers were required to comply with extra transparency measures for certain AI systems such as emotion recognition systems, biometric categorisation systems, and generative AI models that produce image, audio or video content that appreciably resembles existing persons. There are no new changes to this article in the EP version of the EU AI Act.

Most of the obligations stated above require minimum effort on the side of deployers. Therefore, it is safe to say that the initial version of the EU AI Act brought very limited implications for the deployers of high-risk AI systems. There are several reasons for that:

- Innovation and investment incentives always come into play when talking about legal obligations, especially with the increasing regulatory burden coming with the “EU Strategy for Data” (DMA, DSA, AI Act, Data Act, DGA, possibly e-Privacy Regulation, Cyber Resilience Act and more…);

- Brussels is a melting pot of the world’s lobbying scene and the EU AI Act has taken its toll on this fact. A report published by Corporate Europe Observatory on 23 February 2023 has shown how several tech companies have engaged with European legislators in order to promote self-assessments and less regulatory load around AI systems.

On the other side of the spectrum, European Digital Rights (EDRi) has published a call to urge the legislators to involve more obligations for the user side when a high-risk AI system comes into play.

According to EDRi; the initial version of the EU AI Act imposed minimal obligations for deployers and EDRi has called the legislators to include i) more obligations on users and especially ii) a fundamental rights impact assessment detailing the specific information in the context of the use of an AI system.

Where do we stand today in terms of deployers’ obligations?

The EP version of the EU AI Act has imposed significant changes to the obligations of deployers of high-risk AI systems. Article 29 of the EP version of the EU AI Act explains the general obligations of deployers of high-risk AI systems:

Instructions of use: mostly unchanged

The obligation to “take appropriate technical and organisational measures” to use high-risk AI systems in accordance with their “instructions of use” issued by the providers remains mostly unchanged. Instructions of use refer to the information provided by the provider relating to the intended purpose and proper use as well as the necessary precautions to be taken.

However, there is an important twist relating to the significance of “instructions of use“: if the deployer makes a substantial modification to the high-risk AI system in a way that it remains a high-risk AI system in accordance with Article 6 of the EP version of the EU AI Act, “deployers” become “providers” in terms of obligations.

Input data: slight but meaningful changes.

The obligation to ensure that input data is relevant in view of the intended purpose of the high-risk AI system when the deployer controls input data. The EP has added to the body of the proposed text that the input data shall also be “sufficiently representative”, meaning that training datasets shall not have a racial, social, religious or any type of bias occurring due to a faulty representation of input data.

Compliance with instructions of use and reporting: important changes

The EP version of the EU AI Act requires the deployers to also inform the relevant national supervisory authorities when compliance with the instructions of use may result in a risk defined as in Article 65(1) of this version. The requirement to notify the national supervisory authority is a remarkable addition that is discussed below in more detail.

Logs of high-risk AI systems: significant changes.

The EP has made significant changes to this particular obligation relating to logs of AI systems. First of all, the logs will be kept only to the degree that they are necessary for ensuring and demonstrating compliance with the EU AI Act and several other purposes stated in Article 29 such as ex-post audits, technical requirements, and incident recordings. Therefore, it implicitly brings a “clean-up” obligation for irrelevant logs of AI systems. This is indeed a good step forward as logs often include personal data and the GDPR requires data minimisation in the processing of personal data. Similarly, the retention period of the logs shall be kept for at least 6 months, and the exact retention period is to be defined particularly by industry standards and taking the intended use of the high-risk AI system into account.

Sectoral legislation: stays unchanged

The obligation to abide by the sectoral legislation that interact with high-risk AI systems will not be affected by the AI Act.

Human oversight and human resources: new provision

The EP version of the EU AI Act adds up a new obligation for the deployers of high-risk AI systems. Article 29(1)a defines that deployers will have to implement human oversight in a way to fulfil the standards of the EU AI Act and to ensure that the human resource handling is properly qualified and trained.

Robustness and cybersecurity: new obligation added

The EP version of the EU AI Act also requires deployers to regularly monitor, adjust and update the robustness and the cybersecurity measures of their high-risk AI systems.

Consultation with workers’ representatives: new obligation added

In a fully-new proposed obligation, the EP version of the EU AI Act requires the deployers to consult with workers’ representatives before any high-risk AI systems in the workplace are put into service or use and to inform the affected employees. Consultation with workers’ representatives is effectively used in many Member States such as the Netherlands or Belgium for various other purposes such as employee monitoring discussions, and camera surveillance in the workplace and EU AI Act will likely be a topic of the agenda in the coming years as well.

Registration to the EU database: new obligation added

The EP version of the EU AI Act in Article 51 requires two different types of deployers (public authorities or Union institutions, bodies, offices or agencies or deployers acting on their behalf, and deployers who are undertakings designated as gatekeeper under Regulation 2022/1925 (Digital Markets Act)) to register the use of their high-risk AI systems to the EU database referred in Article 60. Those who are not obliged to register can still voluntarily register to the database as well.

Remarkable Additions: Data Protection Impact Assessment and Fundamental Rights Impact Assessment for High-risk AI systems

The EP version of the EU AI Act requires the deployers to conduct a data protection impact assessment (DPIA) in Article 29(6), under the same requirements of the GDPR (i.e., when personal data is processed throughout the life-cycle of the AI system). There are two remarkable additions by the EP relating to this obligation.

First of all, the DPIA seems to be obligatory for any high-risk AI system and the data controllers in the sense of the GDPR cannot justify the lack of a DPIA by the DPIA criteria defined by the GDPR. DPIA are obligatory, according to the GDPR, when data processing in hand poses a high risk for the freedoms and rights of individuals however what constitutes a high-risk is not clearly categorized and dictated by the GDPR itself. Therefore, this obligation can be interpreted very narrowly in a way that the EP wants to abstain from a scenario that high-risk AI systems in the sense of the EU AI Act are deemed/evaluated as “not high risk” within the DPIA framework of the GDPR, therefore not triggering a DPIA.

And second, a summary of the findings of the DPIA shall be published in the terms presented by Article 29(6). DPIAs are often not published and in fact, it is very rare that DPIAs are published at all by data controllers under the requirements of the GDPR. They are mostly viewed as a stamping exercise to proceed with the business needs of the data controller and although we do not have a statistic, it is safe to say that most findings of DPIAs are accessory and do not come with sincere efforts to mitigate the risks caused by the processing of personal data. Therefore, with this new obligation, deployers or data controllers will have to step up their efforts to ensure compliance with the GDPR requirements as well. This a good step forward for transparency and accountability that will trigger a more transparent data protection practice as well.

The EP version of the EU AI Act requires users of high-risk systems to conduct a fundamental rights impact assessment (FRIA) to consider their potential impact on the fundamental rights of the affected people. The details are defined in Article 29(a) of the EP version of the EU AI Act and the “minimum” of what a FRIA should include is extensively explained.

Learning on the lessons provided by the GDPR’s experience with the DPIAs, now, the EP version of the EU AI Act clearly states that if the detected risks cannot be mitigated, deployers shall refrain from using such a high-risk AI system altogether. On the bright side for deployers, they will be able to benefit from the existing assessments catered by the providers to the extent that the provided assessment includes the minimum elements defined by the EU AI Act.

Phenomenally and unusually, the EP version of the EU AI Act also requires the deployers to communicate the FRIA to the national supervisory authorities. The manner in which the “notification” will be operationalised is yet to be clearly defined. For the time being, questions over the scope of this notification are still yet to be defined by the EU authorities through the issuing of guidance and explanations.

Moreover, “to the best extent possible” affected group representatives’ such as equality bodies, consumer protection agencies, and data protection agencies (although, personally, I am not really sure what a data protection agency is), will be sitting on the discussion table when the effects of the specific high-risk AI system over fundamental rights of the affected persons are being evaluated.

Finally, like the DPIA obligation, both the FRIA and a summary shall be published. This obligation seems to be referring to a “public” publication, that can be accessed by anyone. However, there is the possibility that access can also be limited to those affected by the use of the high-risk AI system (especially for the use of high-risk AI systems in the workplace).

What will the Council say?

The discussions in the European Parliament have taken longer than expected as the Council has adopted its position for the so-called trilogue on 25 November 2022. Now, it is time that the main institutions of the European Union to start debating the EU AI Act’s final outcome. The EP has shown its interest to indicate that the fair and safe development and use of AI systems in the EU require the efforts of deployers as well. Nevertheless, traditionally, the EP’s strong emphasis on the rigid protection of rights in legislative texts is counterbalanced by the economic and social interests of the Member States present in the Council.

Therefore, it is likely that there will be objections to the current EP version of the EU AI Act, especially on the obligations of deployers as these obligations bring a significant burden on usual and ordinary businesses of the Member States, who would “buy” a high-risk AI system for various purposes.

I expect the discussions to evolve in a direction defending that most of the initially proposed obligations of the EU AI Act to be kept in the final version, but to substantially change those obligations set out over the FRIA and DPIA. On the side of the FRIA, I foresee that the Council would strictly object to;

- The “minimum” elements list of the FRIA, which has nine different domains (including specific risks of harm to likely impact marginalised persons or vulnerable groups) that require an immense human effort and capability;

- Publication of summaries of findings of DPIAs and FRIAs (due to the fact that DPIAs are regulated by the GDPR and there is not an obligation to publish them under data protection regulation, and most business companies do not have the necessary sources to conduct a meaningful FRIA);

- Involvement of representatives of affected groups in the FRIA brings lots of questions around how and when and would further complexify the procedure, even if it is inherently vague due to the incorporation and interpretation of most fundamental rights.

However, my personal stance is that the EU is at a crossroads in defining the rulebook of AI in the EU for the upcoming decades and it has a global responsibility as the most advanced human rights protector and promoter in world geopolitics.

A safe, fair, non-discriminatory development and use of algorithms, therefore AI systems, within the EU, will only be possible if not only developers but also deployers/users of AI systems are held liable for their activities based on algorithms. This point of view arising from the EP shall be kept within the final version of the text as well.

Therefore, I believe that the Commission should also back the EP as much as possible in terms of the obligations put forward to apply to deployers and the EU shall do whatever is necessary to hold the use of AI accountable, even if it would mean imposing abnormal regulatory burdens for those who want to benefit from high-risk AI systems by using them.

_________

[1] The list is not definitive and it is undergoing changes due to the ongoing legislative procedure.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Competition Law Blog, please subscribe here.