On February 7, the Competition Appeals Tribunal (CAT) delivered its first judgment on the merits of the claims for damages concerning the cartel of truck manufacturers ([2023] CAT 6). The judgment resolves the first two processes against DAF Trucks NV that had been initiated by Royal Mail and British Telecom (1284/5/7/18 (T) and 1290/5/7/18 (T)) in the “first wave” of claims for damages caused by the trucks cartel (AT.39824) filed in UK courts against DAF, Daimler, Iveco, MAN and Volvo/Renault). Two subsequent rulings on March 3 set the total amounts of compensation awarded (Royal Mail, here, and British Telecom, here).

| Cartelized Sales | Cartelized trucks | Amount

requested |

Amount Awarded | Interests | |

| Royal Mail | £260.597.683 | 8.108 | £29.815.624 | £15.702.463 | £19.400.249 (compound) |

| BT | £44.961.617 | 1.868 | £4.972.063 | £1.974.068 | £1.461.696 (simple) |

The processing of the first claims had already been stayed a few months ago due to some agreements reached by the defendants with various plaintiffs (Ryder with MAN, IVECO, Volvo and Daimler and Dawsongroup with Daimler and Renault).

“First Wave” proceedings

| Reference | Parties | Initiation | Status |

| 1284/5/7/18 (T)

|

Royal Mail Group Ltd. v DAF Trucks Ltd. | HC-2016-003442. High Court of Justice England & Wales | Judgment of 7/2/23 |

| 1290/5/7/18 (T)

|

BT Group PLC et al. v DAF Trucks Ltd | CP-2017-000014. High Court of Justice England & Wales | Judgment of 7/2/23 |

| 1291/5/7/18 (T)

|

Ryder Ltd. & Hill Hire Ltd. v MAN SE et al. | CP-2017-000022. High Court of Justice England & Wales | Stay/Settlement |

| 1295/5/7/18 (T)

|

Dawsongroup plc et al. v DAF Trucks N.V. et al. | CP-2017-000020. High Court of Justice England & Wales | Stay/settlement |

| 1293/5/7/18 (T)

|

Veolia Environnement S.A. et al. v Fiat Chrysler Automobiles N.V. et al. | HC-2017-001941. High Court of Justice England & Wales | VSW proceedings |

| 1292/5/7/18 (T)

|

Suez Groupe SAS et al. v Fiat Chrysler Automobiles N.V. et al. | HC-2017-001941 CP-2017-000023. High Court of Justice England & Wales | VSW proceedings |

| 1294/5/7/18 (T)

|

Wolseley UK Ltd. et al. v Fiat Chrysler Automobiles N.V. et al. | CP-2017-00002. High Court of Justice England & Wales | VSW proceedings |

The “front-runner” claims were followed by nine additional claims (“second wave” proceedings), which are currently in the pipeline. In addition, two class actions were also filed: one “opt-in” (Road Haulage Association Ltd.) against IVECO, MAN and DAF (1289/7/7/18), and another “opt-out” (UK Trucks Claim Ltd. ) against IVECO and Daimler (1282/7/7/18), which were suspended until the judgment of the UK Supreme Court of 11/12/20, Merricks v. Mastercard, [2020] UKSC 51.

“Second Wave” proceedings

| Reference | Parties | Initiation |

| 1296/5/7/18 | Arla Foods AMBA et al. v Fiat Chrysler Automobiles N.V. & CNH Industrial N.V. | CAT |

| 1327/5/7/19 (T) | Kent Frozen Foods Ltd. v Fiat Chrysler Automobiles N.V. & CNH Industrial N.V. | CP-2018-000036. High Court of Justice England & Wales |

| 1338/5/7/20 (T) | Adnams PLC et al. v DAF Trucks Ltd. et al. | CP-2018-000035. High Court of Justice England & Wales |

| 1343/5/7/20 (T) | DS Smith Paper Ltd. et al. v MAN SE et al. | CP-2019-000019. High Court of Justice England & Wales |

| 1355/5/7/20 (T) Hausfeld proceedings | Hertz Autovermietung GmbH et al. v Fiat Chrysler Automobiles N.V. et al. | CP-2019-000030. High Court of Justice England & Wales |

| 1356/5/7/20 (T) Hausfeld proceedings | Balfour Beatty Group Ltd. et al v Fiat Chrysler Automobiles N.V. et al | CP-2018-000033. High Court of Justice England & Wales |

| 1358/5/7/20 (T) Hausfeld proceedings | Zamenhof Exploitation et al. v Fiat Chrysler Automobiles N.V. et al | CP-2018-000032. High Court of Justice England & Wales |

| 1371/5/7/20 (T) Hausfeld proceedings | BOC Group Lt. et al v Fiat Chrysler Automobiles N.V. et al. | CP-2020-000006. High Court of Justice England & Wales |

| 1372/5/7/20 (T) Hausfeld proceedings | GIST Ltd. et al v Fiat Chrysler Automobiles N.V. et al. | CP-2020-000007. High Court of Justice England & Wales |

Reportedly, there had been more than 600,000 cartelized trucks in the UK (“Truck cartel claim could reach £5bn” Commercial Fleet 3/9/18), thus it is not surprising that a dozen additional lawsuits have continued to be filed subsequently (suspended until the CAT judgment of 7/2/23 was delivered).

| Reference | Parties | Initiation |

| 1360/5/7/20 (T) | BFS Group Ltd. et al. v DAF Trucks Ltd. et al. | CP-2019-000015. High Court of Justice England & Wales |

| 1361/5/7/20 (T) | Enterprise Rent-a-Car UK Ltd. v DAF Trucks Ltd. et al. | CP-2019-000036. High Court of Justice England & Wales |

| 1362/5/7/20 (T) | ABF Grain Products Ltd. et al v DAF Trucks Ltd. et al | CP-2019-000037. High Court of Justice England & Wales |

| 1386/5/7/20 (T) | Lafargeholcim Ltd. et al. v Aktiebolaget Volvo et al. | CP-2019-000026. High Court of Justice England & Wales |

| 1417/5/7/21 (T) | Dan Ryan Truck Rental Limited & Others v DAF Trucks Limited et al. | CP-2020-000020. High Court of Justice England & Wales |

| 1420/5/7/21 (T) | A to Z Catering Supplies Limited & Others v DAF Trucks Limited et al. | CP-2020-000021, High Court of Justice England & Wales |

| 1431/5/7/22 (T) | Adur District Council & Others v TRATON SE et al. | CL-2020-000761. High Court of Justice England & Wales |

| 1521/5/7/22 (T) | WM Morrison Supermarkets Limited & Others v Volvo Group UK Limited et al. | CP-2021-000011. High Court of Justice England & Wales |

| 1536/5/7/22 (T) | C Faulkner & Sons v Aktiebolaget Volvo (Publ) | 18/030836. High Court of Justice in Northern Ireland |

| 1564/5/7/22 (T) | Grahams The Family Dairy (Processing) Limited v CNH Industrial N.V. | Edinburgh Court of Session |

| 1565/5/7/22 (T) | Grahams The Family Dairy Limited v CNH Industrial N.V. | Edinburgh Court of Session |

| 1566/5/7/22 (T) | Graham’s Dairies Limited, v CNH Industrial N.V. | Edinburgh Court of Session |

Additionally, the judgment discussed in this post seems to have prompted DAF’s rapid negotiation with other claimants: a few days after it was issued, the claims of Dawsongroup, Veolia, Suez, Wolseley, Herz and Balfour against DAF have been stayed “in the terms set forth in a confidential transaction agreement between these parties […], except for the purposes of the enforcement of such terms” [CAT consent orders of 2/28/23, Suez 1292/5/7/18 (T), Wolseley 1294/5/7/18(T), Hertz, 1355/5/7/20(T) and Balfour 1356/5/7/20(T); of 1/3/23 Ryder 1291/5/7/18(T) and of 13/2/23, Dawsongrop, 1295/5/7/18 (T)]. The foregoing would confirm the existing rumour that DAF has offered compensation to large claimants for the settlement of the actions, in terms similar to those contained in the respective CAT judgment (apparently not only in the UK but also in the Netherlands and Germany).

Logically, litigation in the UK presents its particularities, derived from the different impact that the cartel could have had there, the greater flow of information to the process through disclosure and other legal specialties (both substantive and procedural). Even so, given the pan-European nature of the cartel, the pronouncements by the courts in the different countries are of logical interest to the extent that they reveal some insights about the operation of the truck cartel and the quantification of its overcharge. Before the CAT issued its judgment, two rulings by the German Supreme Court (see here and here), a preliminary ruling of the District Court of Amsterdam (see here) and, more recently a judgment by the Portuguese Competition, Regulation and Supervision Court (see here), have attracted a lot of attention from those interested in litigating for damages caused by the trucks cartel.

Relevance of the CAT judgment

The judgment herein discussed resolves the lawsuits filed by Royal Mail and BT for their acquisitions of cartelized trucks in the UK, claiming an overcharge of more than £34 million, plus interest. Naturally, the peculiarities of the impact that the trucks cartel has had in the UK market, as well as the singular condition of these two buyers, who had bought from DAF around 10,000 trucks (paras. 91 and 516; Royal Mail bought 300 to 1.000 trucks per year, para. 62), imply that the use and extension of the CAT pronouncements in the case to claims for acquisitions of cartelized trucks in other countries must be limited and necessarily qualified. Nonetheless, I think that the judgment has considerable relevance for the litigation underway in other European countries, for several reasons:

Firstly, because of the tradition and specialization of the British jurisdiction and the CAT in these matters. Historically, the UK has been a reputable jurisdiction in terms of litigation of antitrust damages and the judgments of its courts are commonly referenced in other jurisdictions. A telling and recent example is BritNed Development Ltd. v. ABB AB and ABB Ltd., [2018] EWHC 2616 (Ch). Although the compensation granted by the High Court of Justice was moderated on appeal (judgment of 10/31/2019 [2019] EWCA Civ 1940), the sophistication of its analysis for the identification of the harm, its causal link to the infringement and the quantification of the overcharge are admirable (the appellate court itself described its analysis as “faultless”). In my opinion, the CAT judgment in the Royal Mail & BT case, accompanied by a similar econometric fanfare, constitutes an exercise comparable to that carried out in the BritNed case (with the limitations existing in relation to the information available on the operation of the trucks cartel and the data constraints for calculating the overcharge on the purchases of cartelized trucks).

Secondly, because the plaintiffs had access to both the confidential version of the Commission Decision and a vast amount of documentation on the cartel investigation contained in the administrative file before the European Commission (excluding leniency and transaction material). Their claims are supported by a richer factual basis, which facilitates the identification of the harm and its causal link with the cartel (“They have pleaded many examples of the collusion derived from those documents and it is certainly true to say that the collusive contacts between the Cartelists were frequent and numerous“, para. 37).

Thirdly, the judgment is the result of a process in which formidable resources have been invested to calculate the overcharge. Apart from access to the Commission’s file, over more than four years, plaintiffs and defendants have had access to thousands of internal documents required by the opposing party (many times protected by “confidentiality circles”) to prove (or not) the existence of the damage and its reduction (or not). Additionally, both plaintiffs and defendants have used several top-level economists (Economic Insight Limited, First Economics Limited and PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP for the plaintiffs; Compass Lexecon and FTI Consulting LLP for the defendants).

In my opinion, the CAT judgment is a sample of first-rate “legal surgery” on the various relevant issues, facilitated by the mechanisms provided by the UK procedural rules, although in the end, the court encountered the same difficulties as courts in other jurisdictions in assessing the expert evidence presented by the parties to quantify the overcharge. Indeed, despite the elaborate account developed by the judgment on the “theory of harm” and the extraordinary account of the passing-on of the overcharge, the Solomonic solution of awarding the claimants half of the compensation requested could seem disappointing. Nothing could be further from the truth; the judgment expressly mentions that the foregoing is the result of the court’s “broad axe”, but it is also the result of the CAT’s “fine brush”, and the reduction in the amount requested by claimants is compensated -at least in part and with respect to Royal Mail- with the grant of juicy compound interest (to an amount that exceeds the overcharge).

A monograph on the damage caused by the trucks cartel

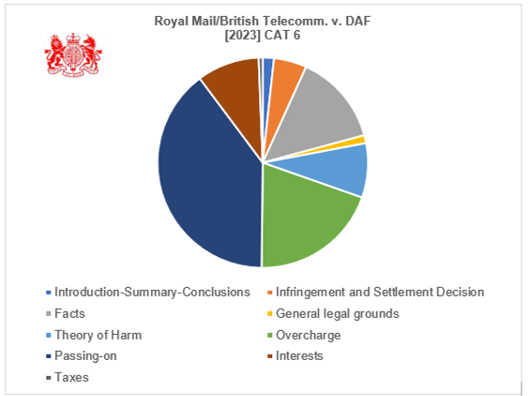

The CAT ruling exceeds 300 pages (104.433 words) and is close in length to that of a monograph on the damage caused by the trucks cartel. The following graph illustrates the division of its content according to the subjects dealt with in it. It is striking that although, logically, a third of the judgment is used to build the “theory of harm” and the quantification of the overcharge (including an elaborate update of the losses via interests), almost half of it is dedicated to discussing and rejecting different alternatives of possible passing-on of the overcharge (mitigation).

Based on the binding effect of the description of the cartel and its operation in the European Commission’s decision (something that the CAT clarified early in Royal Mail Group Ltd. v DAF Trucks Ltd. [2020] CAT 7, confirmed on appeal –[2020] EWCA Civ 1475), the judgment is enriched with the valuable testimony of DAF executives involved in the distribution of trucks to the claimants, which further illustrates how the cartel may have impacted their truck purchases. Undoubtedly, Royal Mail and BT were not standard buyers: they did not buy their trucks from dealers, but directly from the manufacturer through its British subsidiary (indeed, they were the main buyers of DAF trucks in the UK!). Arguably, their potential bargaining power might have counterbalanced the effect of the cartel’s reduction of competition (lowering the overcharge).

DAF admissions

Beyond the binding effect of the decision of the European Commission (article 16.1 of Regulation 1/2003) the court’s starting point is the admission by the defendant (DAF) of various facts related to the operation and impact of the cartel (para. 44.13, “many of the specific examples of collusion that were pleaded by the Claimants […] were based on the disclosure of the Commission’s file“).

Interestingly, DAF accepts here many of the issues that it denies before courts in other jurisdictions, thereby relieving the CAT from having to rule on what, from the moment they are accepted, are considered proven facts. DAF admits that the collusion “was ultimately aimed at restricting price competition […] the Cartelists discussed and informed each other of their respective planned gross price increases, and in some cases agreed those increases, [.. .] the Infringement also included collusion in relation to net prices and net price increases [… and that] ” also included collusion on the timing for the introduction of emission technologies required by EU legislation, and the passing on to customers of the costs of those technologies; for example the Cartelists: (i) agreed not to offer Euro 3 compliant Trucks before it was compulsory to do so; (ii) agreed on a range for the additional price for Euro 3 compliant Trucks; (iii) discussed prices for the technology complying with the Euro 4 and Euro 5 standards; (iv) agreed not to introduce Euro 4 compliant Trucks until September 2004; and (v) shared information regarding the surcharges for EEV compliant vehicles” (para. 42).

DAF’s admission of the above facts is essential because it dismantles the idea that the trucks cartel was an innocuous exchange of information, which the manufacturers organized but which did not have any relevance or impact on the market. Naturally, although DAF’s admission limits its value to the specific process and to its condition as a defendant, it would be difficult to consider that what occurred with DAF did not happen with the rest of the cartelists and did not take place also in other countries. Its relevance transcends the specific process. Despite the foregoing, the CAT takes some time to examine and demonstrate the connection between the gross prices and the net prices of the trucks.

From gross prices to net prices

One of the keys to understanding that the trucks cartel implied an increase in the acquisition prices of vehicles lies in the existence of a connection between the gross prices –on which the collusion of the manufacturers was mainly (but not only) centred– and the net prices. For the CAT the relationship between gross (list) prices and net (transaction) prices of trucks is indisputable.

Indeed, although the European Commission referred vaguely to this connection (paras. 27 and 47 of the Decision), the CAT examines several of the mechanisms used by DAF to manage transferring gross price increases to final net prices of vehicles (DAF control of gross prices, paras. 118-129; margin targets and comprehensive cost prices/IKP, paras. 130-140; DAF consultation/approval and internal control of transactions outside of the objectives, paras. 141-145; premiums obtained in the sale of less polluting trucks in compliance with the standards EURO3, 4 and 5, paras. 146-147). The judgment concludes that there is “evidence that shows that gross list price increases were used to drive up transaction prices, […]” (para. 95). As one of DAF’s executives graphically described, increases in gross prices were not merely “cosmetic” exercise, but they always aspired to translate into net prices (para. 123.2).

The judgment embellishes its theoretical explanation of the link between gross prices and net prices with several illuminating opinions from Mr Ray Ashworth (General Manager of DAF UK for some of the years the cartel lasted) and new evidence on collusion between manufacturers in the UK, confirming the connection between gross prices and net prices, and its commercial relevance -although it may have less of an impact on large truck buyers such as Royal Mail and BT (“Mr. Ashworth indicated that DAF would hope to achieve a transaction price increase that was equivalent to the list price increase, he explained that, in practice, it typically achieved around half the increase with large or direct customers such as the Claimants“, para. 93.2).

Expert evidence

The core of the judgment is dedicated to the assessment of the expert evidence presented by the parties, consisting of 48 reports – amounting to several thousand pages – on different issues related to the identification and quantification of the harm caused by the trucks cartel. Although the reports presented and their discussion during the trial allowed the CAT to acquire a better knowledge of some of those issues, the court reiterates in various passages the impossibility of considering them determinative because, by aligning the opinions of the experts with the interests of their respective clients, they arrived at diametrically opposite results:

“It is perhaps a flaw in the system but in any event appeared quite marked to us in this case that all the experts, […] who opined on a number of different issues, came to conclusions that favoured their clients […]. Perhaps that is an inevitable consequence of the adversarial process and one should expect a party to have an expert that supported their case. But we consider that there should have been more recognition, on certain issues, of the scope for a range of possible results and of the reasonableness of the other expert’s opinion. As they are aware, the experts’ primary duty is to assist us in understanding the factors behind their differing conclusions, rather than defending the conclusions which favoured their respective clients’ positions. When there are fine and difficult issues for us to decide, it is important that we are able to trust the independence of the experts” (para. 235).

In particular, the court ruled extensively on the failure of DAF’s lead expert – Damien J. Neven of Compass Lexecon – to have failed to previously disclose to the Court his past professional relationship with DAF (then as a consultant to Charles River Associates) during the investigation of the cartel by the European Commission and before the settlement decision was adopted, which leads the CAT to conclude: “there is no getting away from the fact that Professor Neven has been involved in advising DAF for nearly a decade and that from a very early stage he was providing his opinion and advice on potential theories of harm that would assist DAF. This situation provided Professor Neven with insights and access that, as an independent expert, we could reasonably have expected him to use in order to assist us. We examine in detail the theory of harm that he puts forward in his evidence in this case and it is safe to say that his conclusion that it is implausible that there were any effects in the UK and on the Claimants from the Infringement is a surprising one. His theory provides a justification for the conclusion that he draws from the data that there was no Overcharge throughout the period of the Infringement. But we are left with the lingering suspicion that, as was disclosed very late on in these proceedings, he had come up with his theory of harm back in 2013 or 2014 (and certainly well before he had access to detailed empirical data), and that has shaped his approach to the expert evidence he has provided on the central issues in relation to the Overcharge” (para. 236).

DAF’s admission of the collusion on gross and net prices, and its purpose of affecting the sale price of trucks does not necessarily mean that prices were higher than they would have been in the absence of the cartel and for this reason, the expert reports presented examine both the “theory of harm”, the calculation of the overcharge and its passing-on.

The “theory of the harm”

The “theory of the harm” lays the foundations for subsequent empirical analysis that seeks to find out through econometric regressions how collusion caused truck sales prices to rise. As was already pointed out by the Commission Decision, the cartel was more than a mere exchange of information on gross prices and their increases (paras. 267 and 270), although the ruling does not advance on the specific way in which the information was used by the cartelists: “The Settlement Decision paints an incomplete picture and DAF has chosen to provide us with no further evidence as to the ways in which the various meetings and exchanges between the Cartelists operated over the 14 year period covered by the Infringement” (para. 278).

Although the defendants eventually argued that the exchange of information would seek to give DAF more confidence as to its own plans and prices or that the information could have been useful in better understanding the relative market positioning of its products compared to those of its fellow cartel members (para. 115), DAF’s own expert witness recognized the speculative nature of this idea, which is far from providing a “pro-competitive credible rationale for sophisticated, profit-maximising firms to have stayed within the Cartel for that period of time with all the attendant risks of doing so” (paras. 272 and 273, more at paras. 283 and 289). Several times in the judgment, the CAT censures DAF’s lack of explanation about the operation of the cartel and the lack of curiosity of its expert in this regard (paras. 18, 266, 291, 299, 308 and 473).

The most plausible explanation of the effects of the cartel on truck sales prices is based on the coordinated effect of collusion (paras. 274-278). The trucks cartel presents some elements that would support a possible coordinated effect of collusion (concentration and a limited number of participants, transparency, and mutual and repeated interaction of the cartelized manufacturers), although given the absence of information on the viability of the coordinated effect of the cartel, at this point the judgment moves to a speculative level. The defendant’s expert denied that the coordination could be effective given the apparent lack of a system for detecting and sanctioning possible deviations from the agreements between the manufacturers (para. 285), but the CAT rejects his entire argument (which started from denying any connection between gross and net prices -and their increases-, paras. 287 and 289). Eventual fluctuations in the market shares held by the cartelists during the collusion would only indicate that the cartel could have been more effective in raising prices if there had been greater discipline, but they do not mean that it did not produce effects (para. 298.4).

In the end, the CAT concludes: “We find that a plausible theory of coordination might be formed around the ability of the Cartelists to use list price increases as a focal point in the hope or expectation that this would make net prices higher. Such might be allied to the monitoring of market shares and feedback from customers on prices whereby the Cartelists could assess whether competing firms had failed to honour the agreement or understanding to raise prices. […] But the clues we do have from the regular Cartel member meetings over 14 years, in which there were several references to net prices among other things, does provide at least a plausible account of how coordinated list price increases might have affected net transaction prices” (para. 320).

On the other hand, without ruling out the coordinated effects of the cartel, the CAT also analyzes the individual behaviour of the cartelists, considering a possible unilateral effect of the collusion. This innovative hypothesis, based on the work of Joseph E. Harrington Jr. “The Anticompetitiveness of a Private Information Exchange of Prices” (published in the International Journal of Industrial Organization 85 (2002) 102793 and on which the District of Amsterdam based its preliminary ruling of 12/5/21, NL:RBAMS:2021:2391), considers that the information exchanged between the cartelists would have been utilized unilaterally by each of them to their pricing decisions (again, see here). However, the ruling does not consider the thesis of the unilateral effects of the cartel convincing (paras. 313-328).

The overcharge and its calculation

Plaintiffs’ and defendants’ experts presented statistical models that, based on prices and market data, try to identify the effect of the cartel on the purchase prices of trucks. Both sides face difficulties in relation to the prices and data used in the econometric regressions and concerning the variables used in the models.

Regarding the data, despite the peculiarities of the claimants as large buyers of trucks, the lack of sufficient observations on the acquisitions made by Royal Mail and BT means that the analysis presented uses the data relating to all sales of DAF trucks in the UK, providing more robustness to the calculation of the eventual overcharge. Certainly, the acquisitions by Royal Mail and BT present singularities derived from their condition as fleet operators with the capacity to negotiate and obtain lower prices (paras. 342-345), but this would not eliminate the effect of the cartel since the relevant comparison must be made with the prices they would have paid in the absence of infringement (para. 153.6).

Given the impossibility of making a geographical comparison between territories affected and not affected by the cartel (due to the wide geographical breadth of the cartel), the experts present several econometric models that compared the effects of the infringement on the prices of acquisitions before, during and after of the infringement (para. 346). Both parties and the CAT recognize the problems faced in calculating the effects of the cartel in the years immediately before and after the cartel, given the uncertainty as to when the effects of the cartel began to be produced and when they ended (paras. 348-353). Indeed, as EURO6 trucks were marketed in 2012 and collusion also affected them, it seems they should be included in the model (paras. 450.5 and 461).

DAF supplied the price databases and other relevant elements used by the experts (Consent Order of 7/21/21), although they contained more information related to the period 2004-2017 (without information by models or on costs of production in the period before that). Based on these data and with differences in the construction of the econometric models, the experts reached different conclusions (“They both recognised the limitations of that data and sought to alleviate this in different ways. It is not surprising to us that each expert has adopted the model that produces a result that is favourable to their client […]”, para. 372). The alternative models of the plaintiff’s expert estimate statistically significant overcharges that oscillate between 11.6% in utilising the 1995-2003 data and 6.7% and 14.5% in utilising the 2004-2007 data (depending on the EURO type of trucks). On the other hand, those of the defendant’s expert estimated slightly negative overcharges.

The discrepancies between the expert models presented are explained by the different periods analyzed (which affects the composition of the sample used), the treatment of costs in those periods in which such information did not exist in the database, due to the different methods of currency conversion of the units in which costs and prices are expressed (Sterling pounds-Euro exchange rates), due to the consideration given in the models of the Global Financial Crisis and the “price premiums” of trucks that included new emission control technologies (EURO3, 4, 5 and EEV).

A detailed analysis of the court’s ruling on each of these issues is beyond the scope of this post, but suffice it to say that depending on the options chosen in each of them, the opposite results were achieved in the calculation of the overcharge (para. 483), and thus the CAT concluded: “In relation to the Overcharge, there are some big and difficult issues in relation to the regression analyses concerning exchange rates, the global financial crisis and emissions standards that significantly affect the outcome of the regression but which seem to us to be difficult and ones on which economics experts could reasonably disagree and on which there may not necessarily be a single correct answer. Many of these issues rest on highly technical choices over the precise specification of the econometric models that the experts employed, the full details of which we could not directly observe. Nevertheless, on all those issues, [the claimant’s and the defendant’s experts] firmly concluded on the side that produced the outcome in favour of their respective clients” (para. 235).

Given the imperfections in the data and the intractable practical problems faced by the models presented, the CAT acknowledges that it is not possible to arrive at an ideal regression equation that calculates the overcharge caused by the cartel. Even so, the judgment concludes that the evidence indicates that it is plausible to consider that the cartel caused an overprice in the purchase of the trucks (para. 476). Although the plaintiff’s expert report raises reasonable doubts about its measurement, it is sufficient to accept that there was a positive overcharge (paras. 477-478). For this reason, without seeking mathematical precision, the court establishes that the compensable overcharge is half of that requested by the plaintiff: 5% of the purchase price of the cartelized vehicles (para. 484). In moderating the amount plaintiffs requested, the CAT claims to follow a “broad axe” approach, which applies to both claimants and for the entire duration of the cartel. The total compensation amount is calculated by including the total amount paid by Royal Mail and BT for purchases of trucks affected by the cartel, including in the sum all extras purchased from DAF (trailers and other add-ons) (para. 473).

Mitigation of the harm: passing on the overcharge

To avoid overcompensation, the CAT undertakes a meticulous analysis to rule out the passing-on of the overcharge by the injured parties. Based on DAF’s allegations and in the reports filed by its experts, the eventual harm caused by the cartel would have been fully mitigated (or even more than that in the case of Royal Mail!) through the acquisition by the injured party of the cheaper trucks’ complements (trailers), the passing-on of the overcharge on the resale of cartelized vehicles, and its transfer (via higher costs) to the prices of the products/services marketed by the claimants.

The judgment analyzes this issue based on the doctrine established by the UK Supreme Court in Sainbury’s Supermarkets v. Visa Europe Services [2020] UKSC 24. On this point, a detailed analysis of the judgment exceeds the aim and scope of this post. The length, completeness, and level of detail of the CAT’s analysis are surely explained (as does the dissenting opinion of Justice Dereck Richard, which lies within it, paras. 692-740) thinking about the relevance that the doctrine established can have for future cases.

Firstly, the passing-on of the overcharge through the acquisition by the injured parties of the cheaper truck complements (trailers) is categorically ruled out as it is too theoretical. Secondly, the CAT also rejected the models presented by the defendant’s expert on a possible passing-on of the overcharge on the resale of vehicles on the used trucks market. Finally, with exhausting thoroughness, the court also examines the possible passing of the overcharge (via increased costs) to the prices of the goods or services marketed downstream by the injured parties. For this to take place, there would need to be a causal relationship between the overcharge and its downstream impact on the price of Royal Mail and BT’s products/services.

DAF should prove this causal connection, which seems complicated in view of the low proportion of said overcharge in relation to the volume of business/expenses of the claimants or their ratio of margins/costs: “although at an abstract level one can envisage that truck costs do form a (small) part of the operating cost of providing a mail delivery or telephone service, there is only an indirect connection between the trucks bought from DAF and the items bought by the Claimants’ customers, such as postage stamps or line rentals” (para. 196 in fine).

The majority of the court rejects that the overcharge had any impact on the prices of the products/services marketed by Royal Mail and BT, in view of their ignorance of the existence of an overcharge that would have raised the prices of the trucks, the tiny proportion of the overcharge with respect to their costs and income (both companies billing billions of pounds while the cartel was in place), the lack of connection between the overcharge and the eventual price increases of the products/services marketed by them and the absence of claims of the indirect purchasers for the overcharge caused by the cartel. The overcharge is far too removed from the prices charged downstream by Royal Mail and BT to their customers, and this lack of connection and lack of proximity makes it difficult for DAF to be able to satisfy a sufficient legal causation test. In addition, in the case of these two companies, the analysis of these issues presents the particularity that they operated during most of the cartel subject to a price control regulation, making it difficult to know what would have happened had the overcharge not existed.

Finally, consistent with the foregoing, as the CAT rules out the possibility of reducing the compensation for any eventual passing-on of the overcharge, it is logical that it should not be appropriate either to adjust the compensation award for a theoretical reduction in the volume of sales of the direct victims of the cartel (Royal Mail and BT).

Interest

Given that the judgment concludes that Royal Mail and BT experienced a loss because of the cartel since they paid an overcharge on the purchases of the cartelized trucks, the amount of the compensable damage must be updated until the moment the compensation is paid. Only Royal Mail requested that the overcharge paid to be discounted with compound interest, leading to a relevant debate on what should be the interest rate used (the interest could range between a little more than £15 million to £85 million, see paras. 758 and 759).

Following previous UK case law (Sempra Metals Limited v Inland Revenue Commissioners, [2007] UKHL 34, and Equitas Limited v Walsham Brothers & Co. Ltd., [2013] EWHC 3264) the CAT decrees compensation for compound interest: “This accords with economic reality and there is no legal bar to compounding the appropriate interest rate that we find to be applicable. This is what happens in the real world and it therefore corresponds to Royal Mail’s actual losses. If it is appropriate to charge interest on a financial transaction, then it is self-evidently appropriate to apply interest also on any interest that has accrued between one period and another” (para. 768).

Even so, the CAT rejects the argument that the calculation of interest should be carried out according to the weighted average cost of capital (WACC). This formula for calculating interest, consistent with the calculation of financing equity, was rejected by the CAT in Sainsbury’s (and by the High Court in BritNed) and is now also rejected by the particularities present in the financing of the Royal Mail. Instead, the interest measure used is built with a combination of its debt financing costs and the return obtained on its short-term investments during the period 1997-2022.

Conclusions

Aside from the procedural and substantive particularities of UK Law and the singularities presented by the claim of the two largest purchasers of DAF trucks in the UK, reading the CAT judgment is enlightening for anyone involved in or fascinated by the considerable international litigation over damage caused by the trucks cartel.

The CAT provides clarification on a range of the issues that are still being discussed in the courts in other countries regarding the trucks cartel overcharge and its causal relationship with the collusion of the cartelists (f.e., just a few weeks ago, the Oslo District Court quashed the damages claim of Posten Norge & Bring, for the acquisition of over 2.000 cartelized trucks in Norway, Sweden and Slovakia). Access to the administrative file of the investigation by the European Commission and the testimonial evidence leave no doubt that it was not an innocuous cartel. Although the bulk of the collusion focused on trucks’ gross prices, the manufacturers’ intention (at least DAF, but presumably the rest as well) was that the increases would be passed on to the (net) transaction prices of the vehicles. Given that Royal Mail and British Telecom bought 10.000 cartelized trucks, and did so directly from DAF UK’s subsidiary, it is not surprising that these purchasers had bargaining power, which would have meant a lower overcharge (half of the regular overcharge, according to the former Managing Director of DAF UK).

The trucks manufacturers sought to affect the final sale prices of the trucks (something accepted by DAF in this process), unfortunately, the CAT failed in getting DAF to shed light on the entrails of the collusion and the specific mechanics of how the information exchanged between the cartelists affected market prices. Despite the intense level of discovery, thousands of pages of expert reports, a dozen preliminary hearings and twenty-five days of oral proceedings, the judgment provides only a partial view of the internal functioning of the cartel.

Given the opacity regarding the details of the cartel and its internal impact on DAF’s commercial offer, the discrepancies in the three main issues facing the models presented by the experts are logical (the euro-pound currency exchange method; the influence of the Global Financial Crisis and the price premiums of trucks that included new emission control technologies), the CAT refused to accept the claimants’ expert report. This also explains the outcome: moderating the compensation award to half of that requested (which, curiously, coincides with what DAF aspired to achieve by transferring the overcharge to large customers, such as Royal Mail and British Telecom), accompanied by compound interest in the case of the first claimant, which doubles the amount of the final award.

__________

* The author is an academic consultant at CCS Abogados, which represents plaintiffs in private litigation on the trucks cartel in Spain.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Competition Law Blog, please subscribe here.