On September 29th 2022, the Commission published Guidelines on the application of Union competition law to collective agreements regarding the working conditions of solo self-employed persons (hereinafter: the Guidelines). The first draft of this document was released almost a year ago as part of a package including a proposed Directive on platform work.

The Guidelines, which cover not only digital labour platforms but solo self-employment in general, can be seen as an important step in calming the contradictions between the right to collective bargaining and EU competition law. [1]

Building on the case law of the Court of Justice and recent legal developments at the EU and Member State level, the Guidelines articulate a carefully worded exemption from Art. 101 TFEU for collective bargaining agreements aimed to improve the working conditions of solo self-employed who are in a comparable situation to workers. The exception is coupled with a commitment of non-enforcement by the Commission for some additional cases of collective agreements on behalf of solo self-employed who are not in a comparable position to workers.

This contribution provides background to the Guidelines and summarizes the conditions for exemption. Finally, it includes a list of questions that can help determine whether a collective agreement can benefit from the newly introduced exemption.

EU competition law and the chilling effect on collective bargaining

To what extent should EU competition law apply to collective labour agreements? This question was answered by the Court of Justice of the European Union in 1999 in the Albany judgment. Instead of giving a ‘carte blanche’ exemption to trade unions, the Court of Justice opted for a conditional carveout for collective labour agreements (paras 60-63).

The two cumulative criteria are:

- That the agreement must be concluded as a result of social dialogue between workers’ organisations and employers’ organisations (the ‘nature’ criterion) and

- That the agreement must aim to improve the working conditions of workers (the ‘purpose’ criterion).

Already before the rise of the gig economy, self-employed, especially in the arts, culture, and media sectors, have struggled with the first criterion of Albany. They qualify as ‘undertakings’ for the purpose of competition law, but they might not fulfil the criteria for ‘worker’ under EU law.

As a result, their representative organisations cannot be seen as ‘workers’ organisations’ engaged in social dialogue for the purpose of the Albany exemption. Rather, they have been seen as ‘associations of undertakings’ (para 28 of the FNV Kunsten judgement). As a result, the self-employed’s attempts to organize or participate in existing collective labour agreements were threatened with legal sanctions by competition authorities. [2]

An important nuance to the first condition of Albany was made in 2014 in the FNV Kunsten judgement. In this reference for a preliminary ruling, a trade union representing orchestra musicians challenged the Dutch competition authority’s pronouncement that a collective agreement on behalf of self-employed falls foul of the cartel prohibition. The Court, while reaffirming that self-employed are to be considered as ‘undertakings’ for the purpose of EU competition law and that agreements between them and employers are not covered by the Albany exception, also clarified that agreements on behalf of ‘false self-employed’ would nonetheless be exempt. Such persons, the Court reasoned, find themselves in a situation comparable to that of workers.

The concept of ‘false self-employed’ introduced in FNV Kunsten did not provide much legal certainty. Essentially it made the right to collective bargaining conditional on an assessment of the labour situation of the self-employed person in question, an assessment in which courts have the ultimate word.

And what if the assessment would show that the self-employed do not fit the EU definition of ‘worker’ or the definition of ‘false self-employed’? Then Article 101 TFEU is triggered with the consequence that the agreement is void and that damages may be claimed. This situation of legal uncertainty was perceived to have a chilling effect on the ability to exercise a fundamental right. [3]

A factor compounding the relevance of the issue is the rapid and continuing growth in self-employment, much of it driven by growth in platform work.

The main contribution of the Guidelines is that it introduces more certainty concerning the first criterion of Albany by introducing a presumption for three types of solo self-employed who are in a position ‘comparable to that of workers’. For those self-employed who do not fit in one of the three categories, but satisfy one of two further conditions, the Commission makes a promise of non-intervention.

What is a collective agreement for the purpose of the Guidelines?

In establishing the conditions that a collective agreement must meet to benefit from the exemption, the Guidelines follow the two Albany criteria, namely the ‘nature’ and ‘purpose’ requirements. Specifically, a collective agreement is defined as “negotiated and concluded between solo self-employed persons or their representatives and their counterparty/-ies to the extent that it, by its nature and purpose, concerns the working conditions of such solo self-employed persons” (para 2(c) of the Guidelines).

Pursuant to the first condition (the ‘nature‘ criterion), the agreement must be concluded between workers (or their representatives) and employers (or their representatives). Agreements could be concluded following any form of collective bargaining recognized in the law or practice of a given Member State. At the same time, the Guidelines also extend to situations in which the self-employed (individually or as a group) request to be covered by an existing agreement between their counterparty and another group of workers or solo self-employed persons (para 14).

The exemption also covers the negotiation phase of a collective labour agreement by recognizing that some exchanges of information and coordination may be justified if they are necessary and proportionate for negotiating or concluding a collective agreement (para 16). The Guidelines make clear that horizontal agreements issued by one side of the market – e.g., a decision by a group of self-employed to charge the same tariff or a decision by employers on a maximum remuneration – are not exempt by the Guidelines.

The second Albany condition is also incorporated into the Guidelines. It states that the agreement must have the purpose of improving working conditions. Unlike the Albany judgment, which is rather laconic on this, the Guidelines do not leave the definition of working conditions to chance. They clarify that “[t]he working conditions of solo self-employed persons include matters such as remuneration, rewards and bonuses, working time and working patterns, holiday, leave, physical spaces where work takes place, health and safety, insurance and social security, and conditions under which solo self-employed persons are entitled to cease providing their services or under which the counterparty is entitled to cease using their services” (para 15).

Collective agreements or clauses which go beyond these will not be exempt. For example, agreements which establish the final cost of the service to the consumer, which divide territories, or impose limitations to the ‘freedom of undertakings to hire the labour providers that they need’ are considered unrelated to the working conditions identified above and thus outside the scope of the exemption. To illustrate, if a ride-hailing platform agrees with its drivers to pay them 10 EUR per ride, this would be covered by the exemption. However, an agreement between drivers and the platform to charge the consumers 10 EUR per ride would not be acceptable (Example 5 of the Guidelines).

Who are the solo self-employed?

The Guidelines only extend to collective agreements which regulate the working conditions of solo self-employed persons. Such a person is one “who does not have an employment contract or who is not in an employment relationship, and who relies primarily on his or her own personal labour for the provision of the services concerned” (para 2(a).

The emphasis on reliance primarily on personal labour is important because it excludes a number of natural persons who provide goods or services on the market (and thus qualify as undertakings). The Guidelines clarify that self-employed for whom the income-generating activity lies in the exploitation of or granting access to an asset, or from selling goods and services are excluded from the scope. This means that an agreement by e.g., Airbnb hosts and the home-sharing platform, or crafters selling their goods or services via platforms such as Etsy or eBay, would not be covered (paras 18 and 19).

Less clear is the question as to whether persons who use labour and capital to provide their services would be covered. Although the Guidelines admit that the use of some equipment (such as cleaning accessories or a musical instrument) does not disqualify one for the purpose of the exemption, uncertainty remains regarding services which involve the use of more costly equipment.

Finally, the Guidelines are silent on what is meant by ‘solo’. Although not explicitly stated, it may be inferred that by ‘solo’ the Commission means a self-employed person who does not employ others. The Commission may have wanted to follow the approach of the Netherlands Competition Authority’s Guidelines on collective bargaining for solo self-employed, in which the target group is limited to those who do not employ others (zelfstandige zonder personnel literally translates to self-employed without personnel). However, this aspect of the definition is not clarified in the Guidelines.

Self-employed in a situation comparable to workers

The exemption is meant for collective agreements on behalf of solo self-employed ‘who find themselves in a position comparable to workers’. In fleshing out this definition the Commission builds on the Court judgments in FNV Kunsten and Confederación Española. In the latter case, the Court considered that a service provider who “does not independently determine his conduct on the market since he depends entirely on his principal, […] because the latter assumes the financial and commercial risks as regards the economic activity concerned’ falls outside the scope of Article 101″ (para. 44 of the judgment).

Based on this case law, as well as on the criteria for dependent self-employment established in some Member States’ legislation, the Commission identifies three categories of solo self-employed whose collective agreements can be exempt:

- Those who are economically dependent on their clients because they derive a large portion of their income from one client.

- Those who are working ‘side-by-side’ with the counterparty’s workers, and

- Those engaged via digital labour platforms

Economically dependent self-employed

The Commission considers that solo self-employed who “provide their services exclusively or predominantly to one counterparty are likely to be in a situation of economic dependence vis-à-vis that counterparty” (para 23).

The rationale behind exempting this category is that these self-employed “do not determine their [commercial] conduct independently on the market and are largely dependent on their counterparty, forming an integral part of its business and thus an economic unit with that counterparty” (para 23). [4]

The benchmark used to operationalize this concept is a share of 50% of annual work-related income deriving from a single counterparty (para. 24). The example given is of a collective agreement for self-employed architects who derive 90% of their income from companies hiring them on a project basis.

Self-employed working side-by-side with employees

Self-employed who ‘perform the same or similar tasks’ as regular workers of the company are considered to be in a comparable situation as workers. Such self-employed “provide their services under the direction of their counterparty and do not bear the commercial risks of the counterparty’s activity or enjoy sufficient independence as regards the performance of the economic activity concerned” (para 26). This sub-category seems to target misclassified workers with the advantage that it takes away the need to reclassify them (para 26).

By introducing this presumption, the Guidelines seem to reduce the legal uncertainty of ex-post assessment implied in FNV Kunsten. As an example of this category, the Guidelines mention self-employed musicians who play side-by-side with regularly employed musicians in orchestras. (Example 4).

Digital labour platform workers

The Guidelines consider that many solo self-employed providing services via digital labour platforms are ‘in a situation comparable to that of workers’. They also note that digital platform workers are often dependent on the platform to reach customers and that the platforms can impose terms and conditions unilaterally without scope for negotiation. The Commission takes into account recent Court judgments declaring such workers to be employees and Member State legislation reclassifying such self-employed as workers.

A digital labour platform is one providing a commercial service which meets all three requirements:

- It is provided, at least in part, at a distance through electronic means, such as a website or a mobile application;

- It is provided at the request of a recipient of the service; and

- It involves, as a necessary and essential component, the organisation of work performed by individuals, irrespective of whether that work is performed online or in a certain location (para 2(d)).

This definition is aligned with the definition used in the proposed Directive on platform work. It might be amended in the future if the definition in the final legal act differs materially from it. [5]

For a platform to be covered by the exemption, it must organise the service provided by the self-employed which implies, “at a minimum, a significant role in matching the demand for the service with the supply of labour by an individual who has a contractual relationship with the digital labour platform and who is available to perform a specific task” (para 30 and 2(d). For example, an agreement between ride-hailing platforms and their drivers would be covered by the exemption. By contrast, platforms which merely provide search results, leads, or advertising do not fall within the scope of the definition.

Non-enforcement (priorities)

What about solo self-employed who are not in a position comparable to workers, as defined above? For some of these collective agreements, the Guidelines do not provide an exemption, but something else: a promise of non-enforcement. It is an interesting feature of the Guidelines and a way for the Commission to provide some legal certainty to those parties whose situation deviates from the conditions described above, without committing to an ex-ante legal assessment of the situation at hand. The commitment to non-enforcement may be beneficial to those collective agreements on behalf of the self-employed when those self-employed do not fall into one of the three categories identified above (economically dependent, working side-by-side, or contracted via a digital labour platform).

Importantly, the criteria related to the nature and purpose of the agreement (the Albany conditions) and the general definition of ‘solo self-employed’ explained above still hold.

The non-enforcement commitment can be invoked in one of two situations:

- When the solo self-employed in question faces buyer power or;

- When the agreement is permitted under EU legislation or national law in pursuit of a social objective.

Buyer power

The Commission acknowledges where solo self-employed persons face parties with ‘a certain level of economic strength’ (buyer power), “collective agreements can be a legitimate means to correct the imbalance in bargaining power between the two sides” (para 33).

Such buyer power is presumed to exist, but is not limited to, in the following cases:

- Where solo self-employed persons negotiate or conclude collective agreements with one or more counterparties which represent the whole of a sector or industry or;

- Where solo self-employed persons negotiate or conclude collective agreements with a counterparty whose aggregate annual turnover and/or annual balance sheet total exceeds EUR 2 million or whose staff headcount is equal to or more than 10 persons, or with several counterparties which jointly exceed one of those thresholds (para 34).

Essentially, following the second criterion, buyer power is presumed to exist every time the counterparty, or the counterparties jointly exceed one of the turnover or personnel criteria for a micro-enterprise as defined in Art. 2(3), Title 1 of the Annex to Commission Recommendation on the definition of SMEs.

An example which illustrates this situation is an agreement between solo self-employed technicians working for three companies in the automotive maintenance and repair services sector with an individual annual turnover of EUR 1 million or less. The individual agreement with each of the companies does not benefit from the presumption of buyer power and thus the promise of non-enforcement; however, an agreement involving all three companies will not be the subject of enforcement by the Commission.

The Guidelines note that the imbalance in bargaining power can also exist in other cases but then the individual circumstances would have to be considered (para 35).

EU law or national legislation in pursuit of a social objective

The Commission also recognizes that some Member States have already enacted legislation aimed to protect collective agreements on behalf of (certain categories of) solo self-employed persons from competition law. Such legislation may take different forms, such as the creation of a right to collective bargaining or an exemption from the national competition law provisions for such agreements.

The Commission’s promise of non-enforcement is carefully worded. The agreements would still have to be ‘collective agreements’ in the sense of the Directive, thus satisfying the ‘nature’ and ‘purpose’ criteria and they must be on behalf of solo self-employed. Furthermore, the national legislation in question must be ‘in pursuit of social objectives’. Examples given include national competition law exemptions for self-employed in the cultural sector or self-employed audiovisual translators.

EU legislation, such as the Copyright Directive, and national measures which implement it, also escape the Commission’s scrutiny. Thus, national legislation which chooses to implement the Copyright Directive need not fear the threat of Commission enforcement. The example provided is of a collective bargaining agreement for self-employed journalists who work on a freelance basis, to negotiate an increase in the royalties or remuneration paid for their articles by newspapers and magazines. However, collective agreements involving collective management organisations or independent management entities are not covered by the promise of non-enforcement (para 40).

What is explicitly NOT covered by the exemption?

To reiterate, the following are not covered by the exemption provided in the Guidelines:

- Horizontal agreements covering only the demand side or only the supply side, that is uni-lateral agreements, be they imposed by the self-employed and their representatives or by the clients and their representatives;

- Agreements or clauses in agreements which go beyond what is needed to improve working conditions. For example, a collective agreement which fixes the price for the final consumer or which limits the client’s freedom concerning its hiring choices;

- Agreements on behalf of solo self-employed who resell goods and services, or where services are not mostly derived from personal labour;

- Agreements on behalf of solo self-employed who share or exploit assets;

- Agreements on behalf of solo self-employed with platforms that do not qualify as ‘digital labour platforms’;

- Collective agreements of collective management organisations or independent management entities.

For such agreements, the competition law rules continue to apply.

Conclusions

The Guidelines come at a time when self-employment, and platform work, in particular, have been on the rise. Although they do not go as far as providing a complete and unconditional exemption or commitment to non-enforcement, they are nonetheless of practical and symbolic significance. They promise to remove, at least partially, the chilling effect that the threat of competition law enforcement has had on collective bargaining initiatives on behalf of the self-employed. The Guidelines also establish that certain agreements in labour markets are likely to infringe competition law, and in that sense, may play a role in educating market parties on a relatively under-explored topic of the application of competition law to labour markets.

Of course, questions regarding the scope of the exemption remain. The self-employed are a wildly heterogeneous group. The Guidelines provide some diversity by mentioning drivers for ride-hailing companies, cleaners, architects, musicians, journalists, translators, and technicians. It remains to be seen which groups will be able to benefit from the exemption and non-enforcement commitment in practice, and which groups may be (inadvertently or not) left behind.

For private parties, of course, the opportunity remains to test the limits of the law before the courts. Guidelines are, after all, just that – Guidelines, and not binding law. They are only binding on the Commission and, at most, on the public enforcers in the Member States who choose to follow the Commission. It is not binding on Courts, which may be seized by private parties pressing for annulment or damages.

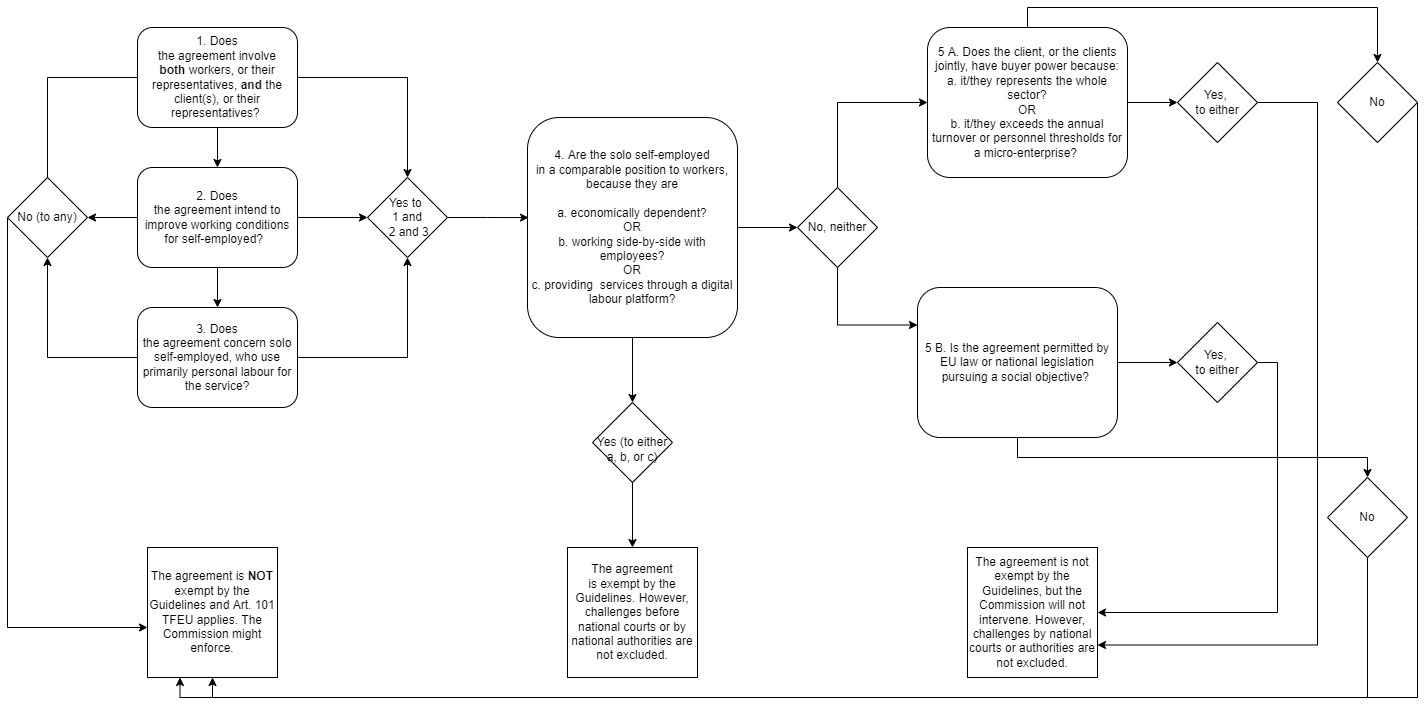

Flowchart (link on the graph to enlarge)

Questions to ask to understand whether a collective agreement covering solo self-employed can benefit from the exemption (or from non-enforcement):

_____________________

[1] The right to collective bargaining is protected in the ICESCR, ILO conventions, the European Convention on Human Rights and the European Social Charter, as well as the EU Charter on Fundamental Rights.

[2] Notable in this respect are cases involving persons in the creative sector such as actors, musicians and journalists. See e.g., Dansk Journalistforbund ctr. Konkurrencerådet (27 April 1999), Competition Authority Decision No E/04/002, Case COM/14/03 (Ireland Competition Act 2002), Nederlandse Mededingingsautoriteit (Dutch Competition Authority), Cao-tariefbepalingen voor zelfstandigen en de Mededingingswet: visiedocument (Collective labor agreements determining fees for self- employed and the competition law: a reflection document) (The Hague, 2007).

[3] See CEPS, EFTHEIA, and HIVA-KU Leuven, Study to gather evidence on the working conditions of platform workers (Brussels, December 2019), p. 253

[4] The Guideline seems to build on the Court’s judgment in C‑217/05 Confederación Española, paras 43 and 44.

[5] The Directive, which aims to improve working conditions in platform work, has not been adopted yet. If passed, it could make it easier for platform workers to be classified as workers.

_________________

The author has served as an independent expert for the European Commission on this topic.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Competition Law Blog, please subscribe here.

This article is really impressive and interesting , You explained this topic very well .The information is really good and interesting .I am great thankful of you for this information.