UK Competition Appeal Tribunal Judgment: Pushing the Envelope on Abuse of Dominance

The CAT’s Royal Mail v Ofcom judgment considers what constitutes abusive conduct, the “as-efficient competitor” test, and the use of expert economic advice.

On 12 November 2019, the UK Competition Appeal Tribunal (the CAT) published its judgment rejecting Royal Mail’s appeal against a £50 million fine imposed by the UK Office of Communications (Ofcom), the UK communications and postal services regulator, for abuse of a dominant position in bulk mail delivery following a complaint from Whistl.

This post focuses on three areas of the CAT’s judgment: (1) the distinction between abusive conduct and mere preparatory acts; (2) the relevance of the “as-efficient competitor” test when assessing exclusionary conduct by dominant companies; and (3) the treatment and protection of expert economic advice.

The UK Postal Services Sector

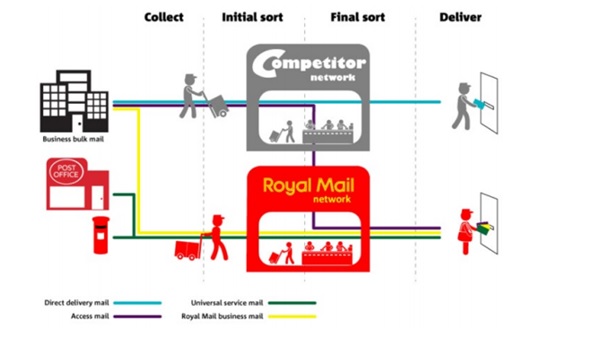

The UK postal services sector was liberalised in the early 2000s. Although Royal Mail is now under private ownership, it continues to operate under important regulatory conditions. First, the company is subject to a universal service obligation to deliver mail to every UK address, six days a week, at a standard price. This obligation does not extend to bulk mail. Second, Royal Mail is required to grant rival postal operators access to its postal delivery network, as shown below.[1]

Figure 1: Forms of competition in the UK postal market

Source: Ofcom, Annual monitoring update on the postal market, figure 3.2.[2]

In principle, liberalisation of the postal services sector could allow competing providers to establish their own “end-to-end” (or “network”) collection and delivery service for parcels and letters. In practice, parcels have attracted significantly more entrants than letters, and most competitors have continued to rely on access to Royal Mail’s network. Royal Mail remains the only nationwide end-to-end operator; rival operators account for less than 1% of end-to-end mail deliveries[3] and have tended to focus on specific metropolitan localities. As the CAT observed, whereas “Ofcom viewed the development of end-to-end competition as a key feature” of the UK regulatory framework, Royal Mail has argued that end-to-end competition risks undermining its financial stability as universal service provider.

- Treading the Line Between “Preparation” and “Conduct”

During the period examined by the CAT, Whistl UK (formerly TNT Post) was Royal Mail’s largest UK postal services competitor. Whistl entered the UK bulk mail segment on an access basis, aiming to develop its own end-to-end capability. By late 2013, Whistl offered end-to-end bulk mail delivery in a handful of areas and was seeking third-party investment to expand. In early 2014, Royal Mail announced differential prices for bulk mail operators to access Royal Mail’s final delivery service. The price differential depended on the extent to which the bulk mail provider matched Royal Mail’s own delivery patterns. Whistl complained to Ofcom that the proposed pricing scheme unfairly discriminated against it and certain of its customers, impeding Whistl’s efforts to develop a competing end-to-end service.

Dominant companies are prohibited from “applying dissimilar conditions to equivalent transactions”, placing others “at a competitive disadvantage”. Many abusive discrimination cases concern allegations — as in the present case — that a dominant provider has withheld or conditioned access to its infrastructure or inputs for rivals seeking to compete downstream. In such cases, the most keenly contested points of law tend to be the importance of the infrastructure/inputs (which Royal Mail did not contest in this case) and whether the conduct was abusive. The question in this case was whether Royal Mail’s announcement of the price differential amounted to “unequal treatment” that materially distorted competition between the dominant firm and its rival. Unusually, the CAT was asked to consider the threshold question of whether publishing the price differential alone constituted conduct.

The novel question arose as a result of the regulatory obligations on Royal Mail to publish contract change notices. Royal Mail duly published the notices, but suspended (and later withdrew) the proposed price increases. Thus, customers were not charged the purportedly discriminatory prices. Royal Mail argued that it had, at most, engaged in preparatory acts. The CAT disagreed, upholding Ofcom’s finding that merely publishing the contract change notices was sufficient to constitute abusive conduct, as this was “a formal, definitive and public step” intended to “cause customers to make appropriate changes to their activities”.

The CAT’s treatment of seemingly inchoate actions risks leaving companies uncertain as to when strategic planning, forward-looking announcements, or negotiations with customers could attract antitrust scrutiny. The answer arguably lies in the probable response of third parties to the company’s actions. The CAT examined the response of Whistl and its customers to Royal Mail’s announcement and found that the contract change notices had interrupted the conversion of Whistl’s customers to its end-to-end service — an indication of likely anti-competitive effects. The CAT (and Ofcom before it) assessed whether Royal Mail’s actions had crystallised into an abuse by reference not solely to Royal Mail’s conduct, but also to the response of third parties.

The CAT’s position seems broadly consistent with Humber Oil Terminals v. Associated British Ports,[4] a similarly rare case analysing when a purported abuse becomes ripe. In that case, the High Court found that a dominant port authority could not abuse its position by proposing an excessive price during negotiations if the counterparty could refuse the offer and rely on a contractual dispute resolution mechanism to resolve the impasse. These alternative options negated the possibility of anti-competitive effects. The CAT’s judgment arguably also finds support in Michelin II,[5] British Airways,[6] and Tomra,[7] which confirm that potential restrictive effects can be sufficient for an abuse. It would seem odd if actions that were capable of producing — but had not yet produced — exclusionary effects amounted to an abuse, while actions shown to produce exclusionary effects did not constitute an abuse simply because the dominant firm could have acted more forcefully.

- The AEC Test Is Not a Silver Bullet

Another important area of the judgment is the CAT’s detailed consideration of the “as-efficient competitor” test (the AEC Test) in exclusionary pricing cases. The AEC Test posits that conduct by a dominant undertaking should be found unlawful only if it would exclude an equally efficient or more efficient rival. For example, below-cost pricing by a dominant firm is considered exclusionary because an as-efficient rival could not match the dominant firm’s pricing without incurring a loss on each unit produced.

The European Commission’s 2010 Guidance Paper on exclusionary abuses adopted the AEC Test as the preferred standard for distinguishing unlawful behaviour from competition on the merits. However, the AEC Test in the Guidance Paper is not a bright line, nor is it binding upon the Commission (or Member State authorities). The Guidance Paper acknowledges that competition from a less-efficient rival may merit protection if, absent any abuse, the rival might be expected to achieve comparable efficiency over time. Finally, the cost benchmarks used to evaluate a rival’s efficiency are soft at the edges: Commission communications preceding the Guidance Paper argued that the cost benchmark should be more generous to rivals in sectors that have been recently liberalised, are undergoing liberalisation, or entail legal monopolies.

Given this background, the CAT’s reluctance to apply the AEC Test may be unsurprising. While the CAT acknowledged that the AEC Test can be “a critical element”, it found in the jurisprudence neither a legal requirement to apply the AEC Test nor a well-defined category of cases where the test could or should be applied. Moreover, the specific circumstances of this case — a recently liberalised sector, characterised by significant economies of scale and high fixed costs, and in which Royal Mail had accrued “advantages and disadvantages […] by virtue of its universal service provider status” — made the AEC Test inappropriate.

The CAT was largely dismissive of the AEC Test as a “self-assessment tool”, as it considered the test to provide “at best a very limited degree of legal certainty and, at worst, none at all”. The judgment seems unduly stern. The AEC Test remains a helpful practical tool, albeit one to be employed with caution and with an appropriate margin for error. Notwithstanding its imperfections, the AEC Test is far more widely employed by European antitrust agencies than alternative tests for delineating permissible and impermissible behaviour (such as the “profit sacrifice” or nebulous “consumer welfare” tests). Indeed, while the CAT was critical of the AEC Test, it nevertheless conducted an extensive analysis of Royal Mail’s proposed AEC Test, implying that the exercise was not wholly without merit. Ultimately, the CAT’s negative remarks concerning the AEC Test may owe more to the specific structural features of the sector and the CAT’s unfavourable view of the design of Royal Mail’s proposed AEC Test.

- Making Best Use of Expert Economic and Legal Advice

Finally, the CAT’s treatment of expert economic evidence has important practical implications. Royal Mail had retained an economic consultancy firm with experience in regulated sectors, Oxera, to advise on Royal Mail’s pricing strategy. In its decision, Ofcom placed considerable weight on confidential economic expert advice obtained by Royal Mail during the strategy planning phase, analysing a range of pricing schemes, which Royal Mail had turned over to Ofcom during its investigation.

On appeal, the CAT attached similar weight to the communications between Oxera and its client. However, the CAT appears to have gone further, seemingly drawing adverse inferences from the absence of corresponding, exculpatory communications. For example, the CAT observed that while Royal Mail had sought to rely on an AEC Test before Ofcom and the CAT, no such analysis was conducted when Royal Mail was planning its strategy. The CAT expressed suspicion that the subsequent AEC Test had “the hallmarks of an ex post facto exercise”. Although Royal Mail contested this characterisation, the CAT indicated that its willingness to accept Royal Mail’s position was undermined by the contrasting levels of disclosure of economic advice. Whereas Royal Mail had disclosed voluminous written advice from Oxera to Royal Mail covering the period before Whistl’s complaint, only limited disclosure of communications between Royal Mail and Oxera had been provided for the period after Whistl’s complaint.

The CAT’s position provides a salutary lesson for companies engaged in challenging strategic analysis that may require the support of external economists and legal counsel. To avoid adverse inferences, companies should ensure that the written record accurately reflects their substantive efforts to design commercial strategy that complies with competition laws. Further, whether advisers are in house or external, those involved should be aware that, from the outset of any discussion, documents and correspondence that are not legally privileged may be subject to review by authorities and disclosure in litigation. Legal advice privilege only protects legal advice given by members of the legal profession to their clients. That protection is unavailable for advice emanating from any other professions, including economists, even if it touches upon legal topics.

[1] See explanation provided in Ofcom’s Annual monitoring update on the postal market.

[2] Available at https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0027/128268/Annual-monitoring-update-postal-market-2017-18.pdf.

[3] “Postal Services”: House of Commons Briefing Paper, Number 6763, December 2018.

[4] [2011] EWHC 352.

[5] Case T-203/01, Manufacture Française Des Pneumatiques Michelin v Commission [2003] ECR II-4071, para 239.

[6] Case T-219/99, British Airways [2003] ECR II-5917, para. 293.

[7] Case C-549/10 P, Tomra Systems ASA v European Commission EU:C:2012:221, paragraph 68.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Competition Law Blog, please subscribe here.