While recent upheavals in global politics have shifted attention far from international taxation matters, the state aid case against Apple continues to fuel intense debates on both sides of the Atlantic. Before we delve deeper into the latest developments of a discourse that has the potential to shape the future of multinational structures, IP licensing, and cross-border taxation, let us recap the stages the case has gone through thus far.

The story thus far

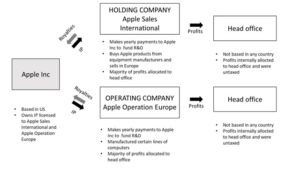

In August 2016, the European Commission concluded its two-year investigation into alleged state aid violations by Ireland and its 1997 and 2007 tax rulings regarding Apple’s corporate profit allocation structure. The structure which Apple utilized until as recently as 2015 relied heavily upon transfer pricing between Apple’s European IP licensee branches and non-domiciliary head offices to which most of profits were allocated to.

Under the corporate structure described above Apple achieved an effective corporate rate of 0.005% in 2014. The tax-efficacy of the structure was powered partly by Ireland’s Tax Consolidation Act of 1997, according to which companies that were incorporated and had trading activity in Ireland, but were ultimately managed and controlled from beyond Ireland’s borders, were not considered to be Irish tax residents. Crucially, the act did not require such companies to be tax residents of any other jurisdiction.

The other key ingredient in Apple’s tax-effective structure were the Irish tax administrators’ tax rulings of 1991 and 2007. These rulings not only sanctioned the corporate structure and interpretation of the Tax Consolidation Act as proposed by Apple, they also fixed the taxable base of Apple’s Irish branches as a portion of operating expenses.

While the Commission does not object to tax rulings per se, it does object to the rulings in question due to their selective nature. Based on the Commission’s calculations, the tax rulings were hand-crafted derivations that may as well be justified under Irish tax regulations, which nevertheless run afoul of the European Union’s state aid rules due to the selective advantage they conferred to Apple.

Accordingly, the Commission held Ireland liable for generating a lawless tax-bounty in excess of 13 billion euros, which it ordered to be recovered from Apple by 3 January 2017. Both Apple and Ireland have sought the annulment of the decision, largely based on the following three questions to which a multitude of conflicting answers have been posed since August 2016.

i. Were the tax rulings state aid?

It is without question that state aid can be granted via individual tax decisions. However, as Ireland rightly argues, it is not immediately clear whether the tax rulings were selective renunciations of tax liabilities or simply legitimate ad hoc applications of a tax framework generally applicable to all corporations similarly situated.

It is similarly uncertain whether state aid regulations are the appropriate vehicle for addressing shortcomings in international taxation or whether they are merely a convenient venue for the Commission due to its extensive powers in the area.

Given that neither the member States nor the Commission have extensive experience in applying state aid regulations to administrative decisions of similar international scope, we can expect the debate to simmer on long after the appeals process has ended.

ii. Should the Arm’s Length Principle Apply to the Corporate Transactions at Hand?

Perhaps the most contentious aspect of the Commission’s theory for recovery is its application of the arm’s length principle. In its decision, the Commission carefully details OECD’s version of the arm’s length principle according to which tax administrations should reject intra-group transfer prices unless they could have been agreed to by independent companies negotiating at arm’s length.

The laudable aim of this principle is to keep multinationals from fabricating their way into artificially low tax-brackets. However, as Apple and Ireland point out, the principle is not a part of Irish tax law or relevant European Union legislation. Rather, in the context of the Irish tax rulings it is a non-binding principle at the heart of current global discussions on international tax reforms. In addition, Ireland notes that even if the principle were a part of the relevant legislative framework, its application would not lead to the outcome the Commission arrived at.

Nevertheless, the Commission recently doubled-down on its view of the applicability of the arm’s length principle in relation to IP-license driven transfer pricing in its recent decision on Luxembourg’s tax rulings on Amazon. However, the intellectual debate on whether the corporate and licensing structures of Apple and Amazon should be held to the ‘uncontrolled’ transactions standards is far from over.

Particularly interesting strands of arguments note that intra-group IP transactions – often in the form of trade secrets or limited exclusive rights – should not be held to the standards of arm’s length deals. To be sure, much of the success of modern multinationals can be traced back to a core of IP around which various distribution, sales, and manufacturing vehicles are built. However, these arguments fail to address the underlying policy concerns that have less to do with notions of overall economic efficiency and dynamic innovation than with the geographical boundaries of fiscal considerations.

Others argue that strict application of the arm’s length principle to internal IP-transfers and other core transactions is antithetical to the very existence of effectively functioning multinationals. To be sure, multinationals often fragment their corporate structures in deference to local jurisdictions and their idiosyncratic requirements rather than tax-evasion. As before, such arguments are hardly persuasive when presented to national tax administrators.

iii. Should the Fruits of IP Fall Where It Is Developed or Where It Is Deployed?

The convoluted arguments of the Commission’s decision and the resultant appeals hide a beguilingly simple question: Who should benefit from the fruits of IP? Unsurprisingly, the Commission petitions for Ireland (i.e. the EU) to receive a greater share of the profits derived from IP via manufacturing, sales, and distribution of Apple’s goods within its boundaries. Apple, the United States treasury, and Ireland respectfully disagree.

In the controversy at hand, legal title to all of Apple’s IP is held by Apple Inc., which has granted territorial licenses to Apple’s two main Irish branches. In return, the three parties have signed a Cost Sharing Agreement according to which R&D expenses are divided as per the percentage of product sales in their territories.

According to recent figures, the Irish branches have covered approximately 55% of these costs, amounting to 1,538,036,000 US dollars in 2011. At the same time, the profits of the Irish branches were allocated to head offices that did not have tax-residency in any country. Consequently, the profits of Apple’s activities were left untaxed in Europe, with internal flows and deferred tax liabilities settling in the United States. As the Commission rightly pointed out, this arrangement would be in peril should the validity of the internal IP transactions be questioned.

Even the Commission agrees that IP is difficult to allocate appropriately given its intangible nature. In order to forward its line of reasoning, the Commission shifted its inquiry into a quasi-analysis of the legal personhood of the Irish branches and noted that ‘since no contractual arrangements can exist between two parts of the same company, the ownership of (tangible or intangible) assets within that company cannot be contractually determined.’ Consequently, from the Commission’s point of view, neither the head offices nor their branches held the IP licenses, but rather, they were held by the company as a whole.

The Commission further noted that neither Apple Sales International nor Apple Operations Europe managed or effectively controlled Apple IP licenses as evidenced by absence of board minutes detailing IP-related discussions. More critically, the Commission argues that given the lack of employees and practical R&D capabilities the head offices did not have the capacity to actively manage IP – a task which the Commission says cannot be ensured through occasional board decisions.

As a result, the Commission concluded that Ireland must take precedence over the transient head offices and the United States as the appropriate resting places for Apple’s bonanza of profits.

Apple’s rebuttal begs to differ. In its fourteen-point appeal, Apple berates the Commission for its ‘fundamental errors’ in failing to understand how the profit-driving decisions on R&D and commercialization of IP are managed and controlled in the United States. In particular, the company argues that the Commission failed to recognize the routine nature of the Irish branches’ operation and the fact that they had no hand in the development or commercialization of IP. Apple further laments the Commission’s misrepresentation of the importance of board minutes and ignoring of other evidence of head office activities.

Accordingly, Apple advocates for the source of the IP to be the true recipient of the profits instead of the country of deployment and sales. Perhaps surprisingly, Ireland fully agrees. In its appeal, the Irish government criticizes the Commission for refusing to acknowledge the role of Apple Inc. in the development and management of Apple’s IP. The Government also critizes the Commission for misattributing Apple’s IP licenses to the Irish branches as inconsistent application of Irish law and the very principles the Commission espoused elsewhere in its decision.

It must also be noted that the Commission’s casual rejection of the intra-group capacity to enter into legally meaningful IP transactions is worrying, and will hopefully receive more attention as the case proceeds.

Resolving an Irish Standoff

The January 2017 deadline for recovering the 13 billion alleged windfall has long since passed, without a single Euro recovered from Apple. The Irish Government’s outright rejection of the decision undoubtedly plays a part in the delay, with the rest explained by the intractability of the task Ireland was forcibly given. As Ireland has noted, it is committed to recovery pending the results of both its recent appeal and its internal calculations of the amount owed, at the earliest by March 2018.

The Commission remains less than impressed by the proposed scheduler. Accordingly, on 4 October the Commission referred the case to the European Court of Justice which will now decide on whether to impose penalty payments on Ireland. The Commission also took the opportunity to remind Ireland and Apple that their appeals do not postpone or otherwise suspend the recovery process and that Ireland must place the received amount into escrow until the appeals have been resolved.

While the fight over Apple’s tax profits is far from over, the Commission has reason to feel confident. In December 2016 the European Court of Justice sided with the Commission by holding selective tax amortization decisions of the Spanish tax administrator as illegal state aid in the Santander/Autogrill decisions. However, these cases dealt with goodwill amortization and it is questionable whether the cases augur ill for Apple and its case revolving around IP-license structures.

All in all, the case promises to become an important landmark among an expeditiously evolving landscape that will have significant repercussions for multinationals and the countries they set up shop in.

Appendix: Case Timeline

i. Tax ruling granted by Ireland in 1991, which in 2007 was replaced by a similar second tax ruling

ASI

1991:

Net profit to be calculated as 12,5% of all branch operating costs excluding

resale materials.

2007: Net profit to be calculated as 10–15% of branch operating costs excluding certain costs, such as those incurred through charges from Apple affiliates

AOE

1991: Net profit to be calculated as 65% of operating expenses up to USD 70 million or 20% of operating expenses, whichever was lower.

2007: Taxable base to be calculated as 10–15% of operating expenses excluding certain costs, such as those incurred through charges from Apple affiliates and a 1–5% IP return

ii. June 2013 – Task Force opened

The European Commission sets up a Task Force on Tax Planning Practices to investigate allegations of questionably favorable tax treatment by member states

iii. 11 June 2014 – Investigations into Apple’s tax treatment opened

As a result of the Task Force’s analysis, the Commission opens an investigation targeting Apple, Starbucks and Fiat

“In the current context of tight public budgets, it is particularly important that large multinationals pay their fair share of taxes. Under the EU’s state aid rules, national authorities cannot take measures allowing certain companies to pay less tax than they should if the tax rules of the Member State were applied in a fair and non-discriminatory way.” Joaquín Almunia, Commission Vice President

iv. 30 August 2016 – Decision against Ireland issued

The Commission concludes that Ireland subverted state aid regulations and granted more than EUR 13 billion in undue tax benefits to Apple. The Commission orders the recovery of the tax benefits as illegal state aid. Full decision here.

v. 9 November 2016- Ireland’s issued

vi. 3 January 2017 – Deadline for recovering EUR 13 billion from Apple

vii. 22 February 2017 – Apple’s grounds for appeal issued

viii. 4 October 2017 – Ireland remains noncompliant, Commission refers case to CJEU

A year after reaching its decision, the Commission notes that Ireland has not made progress in implementing the ruling and refers the case to the CJEU.

“Ireland has to recover up to 13 billion euros in illegal State aid from Apple. However, more than one year after the Commission adopted this decision, Ireland has still not recovered the money, also not in part. We of course understand that recovery in certain cases may be more complex than in others, and we are always ready to assist. But Member States need to make sufficient progress to restore competition. That is why we have today decided to refer Ireland to the EU Court for failing to implement our decision.”

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Competition Law Blog, please subscribe here.

Some quick comments on the above article:

(1) There is no profit allocation to the H/Os in this case. There is merely an attribution of profits to each Irish PE. All profits belong to the company – there is no profit split methodology used in this case.

(2) Although Ireland did not tax non-resident Irish companies on profits which were not attributed to the Irish branches – that is and was standard international tax practice. The author neglected to mention that the USA could have taxed those untaxed profits but it only taxes on the basis of incorporation in the USA (or a PE in the USA). Accordingly, Apple took advantage of the differences between two tax systems. The Court has already accepted in numerous judgments that these “arbitrage” situations can exist – see Gilly, Kerckhaert-Morres and Damseaux judgments for examples. In VAT field see RBS Deutschland.

(3) ALP has been part of Ireland’s tax law since the 1800s prior to the foundation of the Irish Free State. TP methodologies and formal transfer pricing rules were only introduced after the 2010 OECD Model.

(4) The ALP used by the Commission is the principle of equal treatment found in the FEU Treaty and which is a general principle of EU law. The Commission is arguing that an Irish company and a N/Res Irish company with a branch in Ireland should be treated in a comparable way for corporation tax purposes ie in relation to the calculation of their tax base and in relation to the rate of tax applied to that base. Normally, the ALP is an indication of what two independent parties would agree re profit attribution to the PEs. The Court has referred to this as “conditions of free competition” in Forum 187 para. 95.

(5) We know from cases like Thin Cap GLO and SGI, that there may be situations where the formal ALP does not need to be met where, for example, the taxpayer is able to show commercial justification for its transaction. A further example is seen in Lankhorst-Hohorst, where the loans made to the subsidiary could not be made on an ALP basis because no bank would have made such a rescue loan on the facts in question. So the ALP, which is a “guestimate” for the purposes of attributing profits to a PE, is not the end of the matter in assessing dealings between a company and its branch.

(6) Under EU law, Ireland was free to establish the chargeable event for CT, the taxable amount and the tax rates which applied to the various forms of establishments of the companies operating in Ireland, on condition that non-resident companies are not treated in a manner which was discriminatory in comparison with comparable national establishments. (see X v Ministeraad (2017) C-68/15). Thus, Ireland could not tax the non-res Irish companies on profits made by those companies which were not attributable to the Irish PEs.