Ten years ago today, new rules to bolster competition law enforcement in Ireland – set out in the Competition Act 2002 – entered into force.

Introducing the new law, then Minister for Enterprise, Trade and Employment, Mary Harney, heralded “ … a more focused approach towards penalisation of anti-competitive activities, more sensible arrangements for how we handle mergers and acquisitions, and a strengthened Competition Authority.”

How have the 2002 rules fared and why, 10 years later, is the troika pressing for new competition law penalties and a strengthened Competition Authority?

The Boom Years: 2002 – 2008

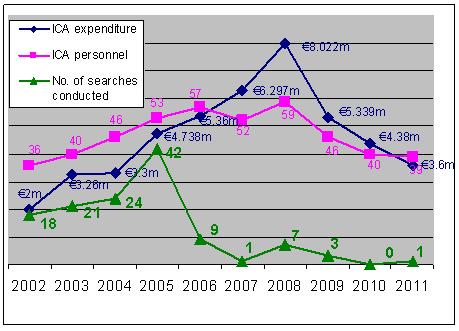

As the table nearby shows, the years immediately following adoption of the 2002 Act were something of a boom period for the Competition Authority. Expenditure increased from €2 million per annum in 2002 to over €8 million per annum in 2008. Over the same period, staff numbers increased from 36 to 59. Operating for much of that period at full capacity, how did the agency perform?

Competition Law Enforcement

Irish business is rife with secretive price fixing, bid rigging and customer sharing according to the Competition Authority. In 2000, then director of the cartels division, Pat Massey, valued the cost of cartels to Irish consumers as £500 million (circa €640 million) and to the economy generally as £1 billion (circa €1.3 billion). The agency operates, claimed then Authority chairman, John Fingleton, in a “target rich environment.”

Hence a primary aim of the 2002 Act was, according to Mary Harney, to “toughen up on hardcore competition offences.” The statute increased the maximum jail sentence for offences from two to five years; the stated aim being to “send the clearest possible signal that blatantly anti-consumer activities such as price-fixing will not be tolerated in this country.”

After some initial success, however, the Competition Authority has struggled to uncover and prosecute competition law violations. The headline statistic cited by agency officials is 33 convictions on indictment. That’s an impressive number, particularly when compared with some other EU countries: in the UK, for instance, no jury convictions have been obtained since criminalisation of cartels in 2003.

But 32 of the 33 Irish convictions were obtained in respect of two cartels; the Galway heating oil and Citroen car dealer cases. More recent prosecutions (of Mayo waste operators and contractors alleged to have rigged a CIE tender) have failed. Indeed, to summarise the last decade, a total of five cartels have been prosecuted by the Competition Authority, two successfully.

What’s more, in some cases, juries seemed reluctant to convict for competition law offences. In one case, following a two-week Central Criminal Court trial, and notwithstanding a two-hour instruction by the judge, the jury returned a unanimous not guilty verdict within 15 minutes. In another, after a six-day trial in the Central Criminal Court including three hours of judge’s instructions, the jury returned a majority not guilty verdict in three hours. To put that in perspective, each prosecution took, on average, three years investigative work to bring to trial.

It would be wrong to fault Competition Authority officials. The agency has looked for innovative ways to improve enforcement. A major first in Irish criminal prosecution was the adoption, in 2001, of a Cartel Immunity Programme jointly with the DPP. This encourages cartel members to self-report in return for immunity and uptake seems to be growing. While the agency does not regularly publish the number of immunity applications it receives, around 20 are believed to have been made since 2001, with four last year. Nor are officials lacking in motivation. The agency’s most successful prosecution to date – the Galway heating oil case – was largely the work of two dedicated and driven staffers.

Overall, however, notwithstanding the agency’s early break-through, the strike rate on cartel prosecutions remains disappointing.

Another stated Competition Authority enforcement priority – tacking monopolisation and other market restrictions – faces similar challenges. Two major enforcement cases were taken by the agency over the last decade: the Irish League of Credit Unions (ILCU) case and the Beef Industry Development Society (BIDS) case.

In ILCU, in which the Competition Authority sought to require ILCU to share services and facilities with a breakaway representative association, the Supreme Court held that the Competition Authority had “failed to provide a convincing analysis of ILCU’s activities as being anti-competitive.” BIDS, in contrast, was ultimately settled in the Competition Authority’s favour, with the Competition Authority recouping some of its legal costs. That outcome, however, took nearly eight years, involving appeal to the Supreme Court and, ultimately, referral to the European Court of Justice.

Indeed, in the last ten years, the Competition Authority has succeeded in obtaining resolution on an abuse of dominance cases in one instance. In a recent settlement with RTÉ, the State broadcaster agreed to abandon suspect “share deal” practices in marketing its TV advertising following Competition Authority investigation of those practices as exclusionary.

At the same time, somewhat surprisingly, the Competition Authority has moved aggressively to apply competition rules to the self-employed. In a controversial 2004 decision, agency officials challenged arrangements establishing set fees for voice-over actors (ranging from €140 to €22) as anti-competitive price fixing between “undertakings.” This position – which rests on an arguable interpretation of the law – denies the self-employed, including vulnerable part-time contract workers, the most basic of rights: collective bargaining. Unforeseen implications – particularly as to how this position impacts on the Government’s ability to deliver health services via collective negotiation with stakeholders like doctors and pharmacies – have been subject to sharp criticism, including by an ex Attorney General. Others use the Competition Authority’s position as a rallying cause for statutory exclusions.

Merger Control

Another key reform of the 2002 statute was the adoption of a new “depoliticised” merger regime, the aim of which was to “take merger control out of the political arena.” Without doubt, the Competition Authority’s operation of the merger control regime – particularly its technical expertise in terms of economic analysis – deserves recognition.

Not that Competition Authority decision-making process on mergers – which is fundamentally an exercise in economic prediction – has been above criticism. In the first and only appeal of a Competition Authority merger decision, the High Court found that the prohibition of Kerry Group’s acquisition of rival Breeo was vitiated by serious error.

But the Competition Authority’s record on merger control (95% of transactions cleared at phase one, 5% involving phase two investigations, and around 0.5% of notified deals blocked) is in line with international best practice. In addition, the transparency of the existing regime and the Competition Authority’s efforts to articulate clearly its rationale in each determination are laudable and, by Irish regulatory standards, fairly unique.

Advocacy

The Competition Authority has an important role in keeping competition in the forefront of economic policy in Ireland. Agency advocacy undoubtedly played a key part in bringing about repeal of the Groceries Order. To estimate accurately the cost of this order to consumers is impossible, but the Competition Authority successfully grabbed headlines with its calculation – cited in a 2003 editorial of the Irish Times, among other media outlets – that the annual cost to the average Irish household of the Groceries Order was, precisely, €481.

The Competition Authority does not always get it right, however. In 2005, after a three-year investigation, the Competition Authority concluded: “[b]anks in Ireland do not compete aggressively for customers.” While the scope of the agency’s review of Irish banking markets was limited, the 2005 report goes on to affirm that “[c]ompetition does not imply a threat to the stability of the financial system. Prudential regulation … ensures that banks act responsibly and prudently, such that the continued stability of the market is maintained. Competition and prudential regulation can coexist comfortably; ensuring a stable banking system that serves consumers, businesses and the economy well.”

Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek’s famously warned of the “pretence of knowledge” – the conceit that central planners and social engineers fully understand complex markets they seek to regulate. No one now seriously thinks that competition and prudential regulation coexisted comfortably in Irish banking markets in 2005. Post crisis, we are left with a duopoly in most Irish banking markets.

The Bubble Bursts: 2009 – 2011

Ostensibly, the financial and economic crisis did not diminish the Competition Authority’s sense of mission. In 2009, then agency Chairman, Bill Prasifka, announced that “competition enforcement and competition policy is even more important in difficult economic times.”

In reality, however, particularly in the final two years of the last Government’s term, the agency suffered existential threat. Likened in 2009 to a “1980s skinhead organisation” by a Dáil deputy from the ruling party, the Chairman of the influential Joint Committee on Enterprise, Trade and Employment openly called for the agency’s abolition. Departing directors were not replaced and an unwanted merger arranged with rival agency, the National Consumer Agency – a proposal publicly attacked by agency officials as a “shot gun” marriage. By late 2010, the Competition Authority was isolated politically, without permanent leadership and in considerable doubt as to its future.

Post crisis budget contractions and a freeze on public sector hiring undoubtedly also hurt Competition Authority resources and staff levels. The table nearby shows agency expenditure fell from over €8 million in 2008 to around €3.6 million in 2011. Over the same period, staff levels fell from 59 to 39.

The Bailout

Enter the troika. One of the first stipulations of EU/IMF bailout officials – set out in the first memorandum of understanding of December 2010 – was to require Government to “introduce reforms to legislation to … empower judges to impose fines and other sanctions in competition cases in order to generate more credible deterrence.” The troika has also required the Government to “increase the resourcing of the Competition Authority to ensure adequate enforcement capacity.”

In light of enforcement challenges, Agency officials have long argued that there is a “major gap in the enforcement mechanism in the 2002 statute”. According to officials, this “serious deficiency” in the law “in practice, means that undertakings can engage in serious infringements of competition law with impunity.” To rectify this apparent lacuna, agency officials lobbied for a system of “civil fines,” to allow judges to impose fines for competition law violations proven to a lower civil law standard (the balance of probabilities, rather than beyond a reasonable doubt).

From recent Dáil debates, advice from the Attorney General seems to have scuppered prospects of such fines. The Government says it has been advised that civil fines for competition law violations – criminalised in Irish law in the 2002 Act – would be unconstitutional. In line with this position, a more recent revised EU/IMF “memorandum of understanding” more generally requires the Government to “bring forward legislation to strengthen competition law enforcement in Ireland by ensuring the availability of effective sanctions.”

Instead of civil fines, the Government proposed legislation in September 2011 to double jail terms for cartel offences from five to ten years. Whether this initiative – certainly not what agency officials were lobbying for – reflects public view of cartels or will otherwise assist in achieve convictions remains to be seen.

As regards promised extra resources, as the table nearby also suggests, this alone may not promote enforcement. Number of searches carried out by the agency each year – usually conducted in serious criminal cases – is doubtless a crude measure of agency activity. But the Competition Authority considers criminal cartels the most egregious form of competition law violation. Deterrence of that conduct is its publicly stated top priority. Assuming surprise searches – so called ‘dawn raids’ – of business and executives’ homes remain an important means to chase cartels, there appears – at least since 2005 – to be unclear correlation between agency resources (in the form of expenditure and staff) and conduct of top priority investigations.

________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Competition Law Blog, please subscribe here.